Why I Don't Trust COAs

An exploration of the contradictions and conflicts of interest in the certificates of authenticity industry

Why I Don’t Trust Certificates of Authenticity and an Argument Why Maybe You Shouldn’t Either

I think Certificates of Authenticity (COAs)1 for autographs are bullshit, and here’s why:

If you can’t trust 100% of a company’s COAs, then you have to double check all of them. That means you are authenticating autographs on your own, so what do you need an authentication service for?

Currently, the largest and most respected autograph authentication service is probably PSA (Professional Sports Authenticator), a subsidiary of Collector’s Universe, a formerly public company that was taken private in a $700 $8502 million hedge fund deal.

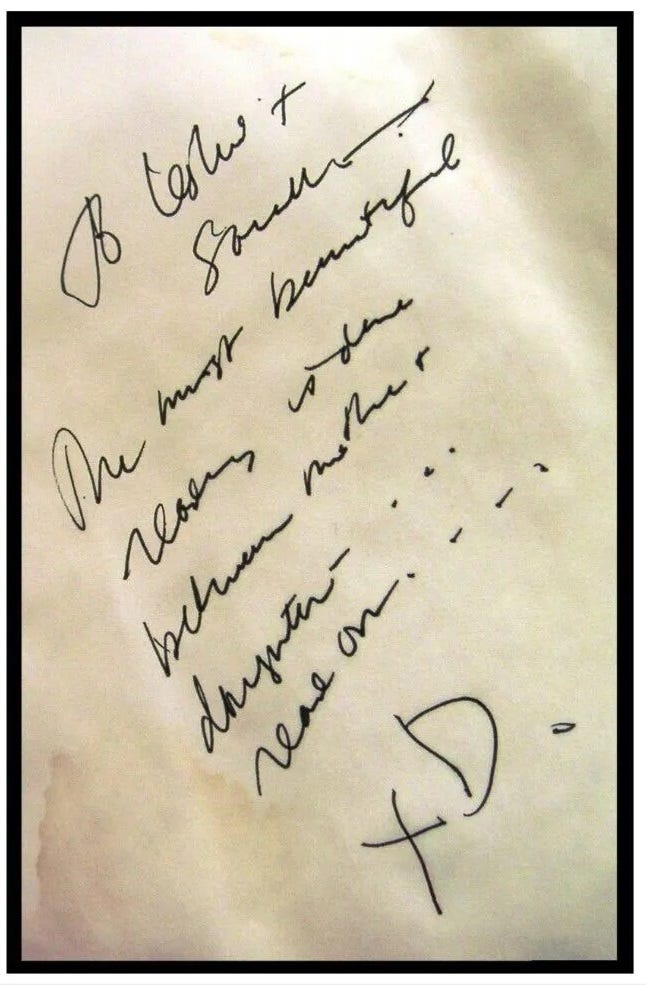

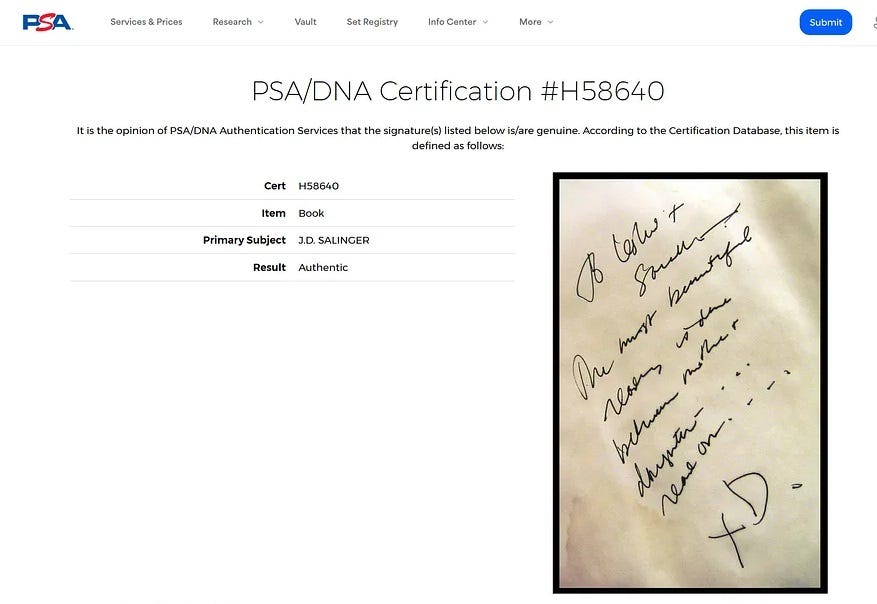

Here’s an example of a famous autograph they authenticated:

I read this as “To Leslie and [?], the most beautiful reading is done between mother and daughter—…read on…. X [love, as in xoxoxo] D[ad].

This inscription is in an otherwise worthless, badly water damaged copy used book. The asking price from an eBay seller was $12,000.

The seller used PSA’s reputation to justify the price: “THIS HAS BEEN AUTHENTICATED BY A RECOGNIZED WORLD LEADER. It is beyond question.”

That’s what PSA would like you to think.3

But this isn’t even a forgery.

It’s just a father4 giving a copy of The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger to his wife and daughter to read together. It was kind of sweet, until PSA said it was a rare inscribed book by Salinger, one of the most reclusive and collectible authors of the 20th century.

Apparently the person at PSA who authenticated the autograph read the signature as “J.D.”—at least that’s the most generous interpretation I can come up with.

Salinger tended to sign his name “J. D. Salinger” but people didn’t call him “J.D.” To those who knew him, he was Jerry. Assigning the autograph to Salinger fails on the basic facts, without even considering the handwriting.5

Back in December, I contacted PSA about this autograph and informed them that they had probably made a mistake. I exchanged several cordial emails with a customer service representative that went nowhere (the cert number was still showing as authentic the last time I checked it). I’d excerpt PSA’s emails but they come with threatening-sounding language about unauthorized quoting that I think is legal mumbo jumbo, but why chance it? I do wonder, though, what they have to hide.

Now you might think that PSA would be concerned about their liability if someone relied on their COA and paid $12,000 for this book, only to learn later that it wasn’t actually signed by Salinger.

Most members of the major bookselling associations (ABAA, IOBA) would feel this way because as long as we are in business, we have to offer money back guarantees to our customers if we sell something that turns out not to be authentic.

PSA calls itself “the only third-party grading service to offer a guarantee on its services,” and it says that the “PSA Authenticity and Grade Guarantee…is fundamental to PSA’s reputation.”

But it’s always good to read the fine print, especially when there’s a hedge fund involved looking to make a significant return on an $850 million investment. By my count, there are currently 18 itemized exceptions to the PSA “guarantee” totaling more than 1600 words (compared to 350 words for the guarantee itself).

Collectors and dealers relying on PSA’s autograph authentication services and COAs should pay attention to this part of the PSA “guarantee”:

“The Guarantee does not apply to the authenticity or grade assigned to any autograph, whether certified by a manufacturer or applied after its release.”

In short, PSA is happy to take your $100 to authenticate a J. D. Salinger autograph but they make no promises about whether their authentication opinion is actually right. Perhaps that’s why they didn’t bother to correct the apparently bogus Salinger I told them about. They got their money. For everyone else, it’s buyer beware.

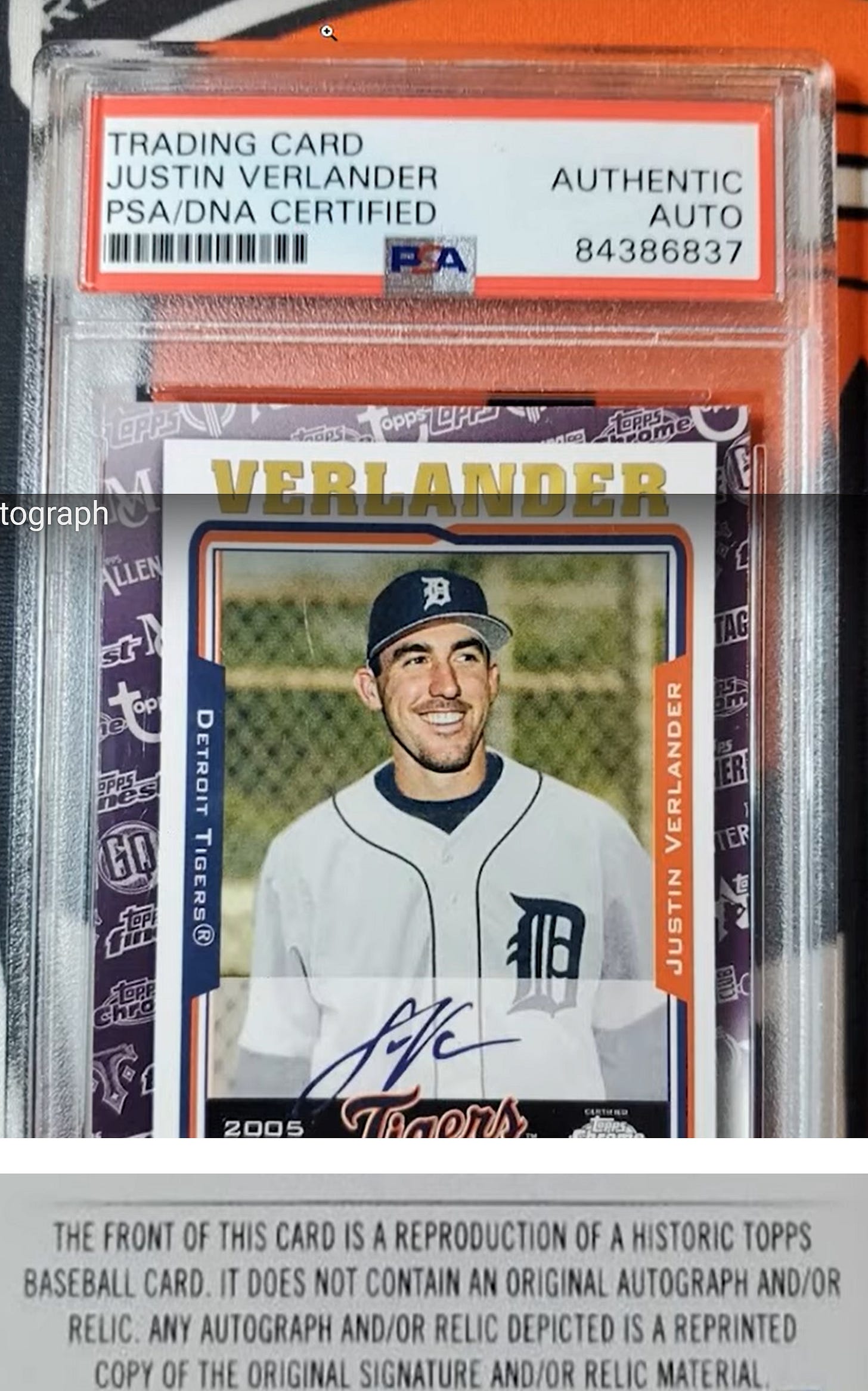

This supposed Salinger autograph is by no means the only time PSA’s authenticators have made an egregious error.6 Here’s a sports card with a printed signature on the front that was encapsulated in an “authentic auto[graph]” plastic slab. To be fair, sometimes it can be hard to tell a printed signature from a real one (but, of course, that’s one of the reasons you might want to hire a professional autograph authenticator).

In this case, however, the back of this Justin Verlander card states twice that the autograph on the front is a reproduction, but PSA took the money and certified it, relying on the autograph exception on their guarantee not to take any responsibility for the error.

Collectors who value COAs from companies like PSA might brush off errors like these as the inevitable result of grading hundreds of thousands of autographs. A few errors are bound to creep in, they might say. But now that you’ve seen one bogus PSA “Salinger” autograph, would you trust their judgment on this one for $98,000? (permalink).

These errors aren’t errors of judgment made by someone trying to identify a real signature from a good forgery. The Salinger I reported to PSA and the printed Verlander autographs aren’t autographs at all. No company that professes to have expert authenticators should ever make this kind of mistake.

And I return to my original point. If you have to second guess any autographs, then all the COAs are effectively worthless because you still have to do your own authentication. COAs are also arguably counterproductive because they cause collectors and dealers to let their guard down and may make them more likely to accept a bad autograph with a COA than a bad autograph without one.

Autograph authentication is hard, particularly when someone is trying to evaluate a simple signature. There are lots of forgers at work; more now than ever before (user saveafricanow on eBay is my personal favorite, both for the volume of forgeries that they sell and for how truly awful all of the “signatures” are).

Even the world’s best handwriting experts will have a hard time identifying a good forgery, particularly when the handwriting example is very small, like the one, two, or three words of a person’s name.

I wondered who the autograph authenticators at PSA are, but of the nearly 800 employees on LinkedIn, none are obviously working on autograph authentication.7 One authenticator I identified got her job following thirteen years working as a “Custom Logo Order Specialist” at Northern Safety and Industrial.

I don’t mean to pick on this employee, but getting good at authentication requires years of experience, none of which is particularly evident in the LinkedIn profiles of Collectors’ (the parent company of PSA) employees.

I searched Justia and found a single US court case where PSA’s opinion about authenticity was accepted by a court, and that was for a baseball card that had been touched up with paint, an objectively obvious alteration that was easily confirmed by other sports-card authenticators.

PSA is not the only autograph authentication company pumping out tens of thousands of COAs each year. Autograph authentication has become an industry with (at least) tens of millions of dollars of sales each year.

James Spence Authentication (JSA) is another autograph authentication firm popular with collectors (James Spence Jr, the founder, also founded PSA’s autograph authentication division. JSA’s COAs are now signed by James Spence III, who is taking over from his father. Update: In May 2024, the comic and coin grading company CGC acquired JSA).

While a much smaller company than PSA, JSA’s LinkedIn page at least has a few people identified as autograph authenticators. But as far as I can tell, neither PSA nor JSA employ former law enforcement officers with experience with forgery, nor are any of their employees identified as belonging to the professional organization, the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners.

According to LinkedIn, one autograph authenticator came to JSA from SGC, a sports card grading company (recently acquired by the hedge-fund-owned parent company of PSA). I don’t want to pick on this fellow, either, but according to his resume he went from an entry-level position at SGC to “director of autograph authentication” in less than 18 months. His previous job, before he became an autograph authenticator? For eight years, he cleaned airplanes between flights for JetBlue.8

As for this employee’s success rate at authenticating autographs, he claims to be “able to achieve 99% accuracy.” Sounds pretty good, but that implies that at least one in every 100 SGC autograph authentication was wrong. As the lead authenticator, this expert said he “authenticated highly valued items autographed by superstars such as Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, and Wayne Gretzky.” Imagine: One year you are picking up pretzels off the floor of a budget airline and the next you are deciding which pieces of paper with “Babe Ruth” written on them are worth tens of thousands of dollars and which are worthless.

(Now that you know that one of JSA’s sports authenticators spent more time working with an airport ground crew than producing COAs, how confident are you in JSA’s authentication of this 5-figure Mickey Mantle autograph certified during his tenure?)

The resume of this expert perfectly captures the circular reasoning at the center of the whole industry of autograph authentication: “Working closely with some of the largest auction houses in the nation,” he writes, “I authored hundreds of LOA’s (Letters of Authenticity) for items which have sold at auction at significant prices.”

In other words, collectors pay large sums for authenticated items and then the authenticators argue that the large sums validate their authentications.

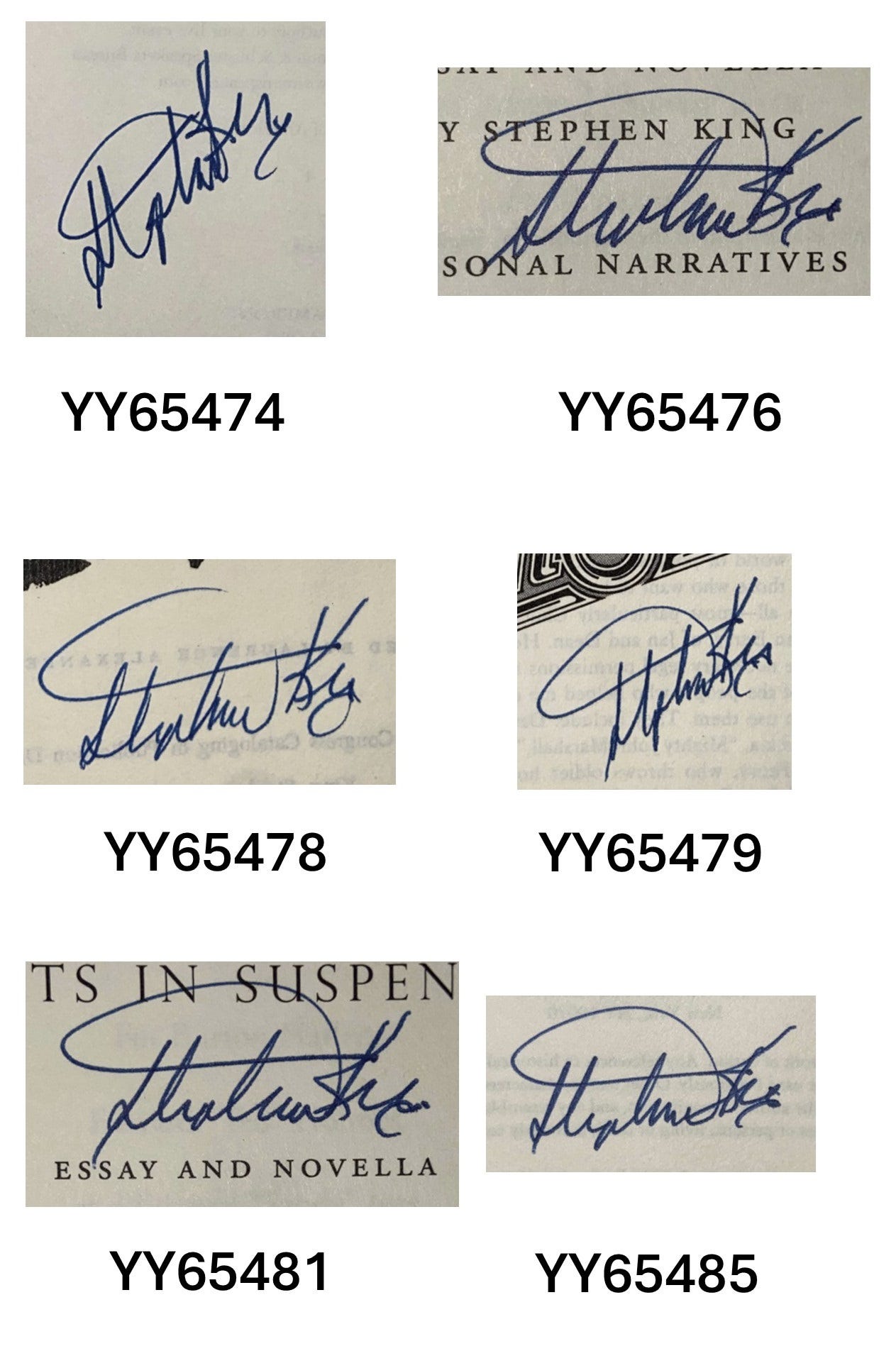

JSA is a prolific issuer of COAs for Stephen King signatures.

King has signed a lot of books over the years, including more than 50,000 signed, limited editions by my estimate.9 For many years, King also let collectors send in books to be signed, and he employed assistants who kept track of all the books and corralled the author into signing them. Despite the large number of real autographs in existence, a King signature often adds $1,000 or more to the price of a book.

In recent years, King has not gone on book tours, nor does he make many personal appearances, yet newly signed Stephen King books keep turning up.

I asked an advanced Stephen King collector about JSA’s COAs for Stephen King autographs. She responded, “Unfortunately it’s prevalent that JSA-authenticated Stephen King signed books are mostly fakes… Furthermore it is in the interest of unscrupulous sellers of fakes to get their copy ‘authenticated.’ ”

I did a bit of digging.

On January 4, 2024, some lucky person had six King books authenticated by JSA. The ink is still fresh and shiny, and yet they look like Stephen King signatures from ten years ago. Nevertheless, these autographs were issued certificates YY73722, -23, -24, -25, -26, and -27.10 Impressive!

Not nearly as impressive, however, as the run of 38 Stephen King autographs consecutively authenticated by JSA on or about December 6, 2023 (beginning with letter of authenticity no. YY65473 and ending with YY65511. You can easily check the adjacent certificates by simply changing the URL in your browser’s address bar).

A number of books from that amazing haul turned up in the eBay store A&E Sports hosted by the seller y2littlek. They recently sold a 9th printing of the Perennial Classics reprint of King’s classic On Writing for $1,499 (available new, not signed, on Amazon, for $17.49). That book came with JSA’s letter of authenticity no. YY65493.

Several of these 38 autographs are very atypical of Stephen King. Even if they were real and signed under some extremely unusual circumstance, it’s hard to understand how JSA can authenticate them; at best an autograph expert should say their opinion is inconclusive. (This is another problem with the authentication business. They give refunds or credits if they can’t reach an opinion; absent scientific testing or detailed provenance research, a lot of autographs should come back inconclusive, but the COA mills don’t make any money if they say that.)

If someone handed in a stack of 38 books signed by Stephen King for evaluation, I think any professional autograph expert should be very skeptical. Of the thousands of Stephen King collectors out there, not very many have managed to acquire 38 signed trade (not limited) editions. How likely is it that a sports guy like y2littlek would turn up a world-class collection of books signed by Stephen King?

Herein lies another contradiction at the heart of autograph authentication—the firms and their customers both want the same thing: lots of real autographs. When a business that should be skeptical is dependent on giving the positive results their customers want, they have a conflict of interest. If JSA doesn’t return enough positive results, the customer can turn to PSA, or Beckett, or others. Collectors who buy autographs accompanied by COAs are not actually the authenticators’ customers, they just rely on the authenticators’ opinions. (It’s exactly the situation in this scene in The Big Short about how the rating agencies gave good marks to junk mortgage bonds, helping to perpetuate the banking crisis of 2008).

Like all businesses, PSA and JSA rely on large-volume customers to drive profits. Large-volume customers will switch services if they pay for too many autographs that come back as fake. JSA charges $50 for a Stephen King COA so a batch of 38 books means almost $2,000 in revenue; the eBay seller y2littlek has nearly 700 items listed that are accompanied by JSA COAs, which equals piles of money for JSA. This is exactly the sort of situation that can lead to errors in judgment. When their livelihood is at stake, even people with good intentions can be swayed to make decisions they might not normally make.

If you find my arguments compelling, a collector might reasonably ask what they should do if they want to collect signed books. Fundamentally, the desire for a COA reflects a keen wish for certainty. The COA companies feed this with their “letters of authenticity” and “certificate numbers,” while renouncing all guarantees in their fine print (JSA’s policies state, “JSA makes no warranty or representation and shall have no liability whatsoever to the customer for the opinion rendered by JSA on any submission.”) Certainty about autographs cannot be 100%. Even if you witness the autograph session, you can’t transfer that memory to anyone else. We are all stuck making our own judgment calls.

But here are a few guidelines:

Buy signed, limited editions. Sometimes they are fake, but not often.

Buy inscribed books, rather than simply signed books. This goes against the current collecting trend, but the more a forger has to write, the harder it is to make a convincing forgery (the exceptions are Ken Kesey and Hunter S. Thompson, whose autographs are almost a caricature to begin with).

Learn all you can about the signers you collect and the basics of forgery detection. Kenneth Rendell’s Forging History: The Detection of Fake Letters and Documents is a good start.

Buy more often from booksellers (like me, :-) who actually guarantee their autographs, as all members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (ABAA), the Independent Online Booksellers Association (IOBA), and the Professional Autograph Dealers Association (PADA) must do. The guarantee is only good as long as the booksellers are members of the organization, but considering that the COA companies offer no guarantees, it’s a much better deal however long it lasts. To be fair, the ABAA is not filled with angels. There have been member dealers connected to forgery and theft, but as long as the dealers are members, they will take returns of inauthentic items sold by mistake, and both IOBA and the ABAA have ethics committees that will mediate between customers and dealers, services that none of the COA companies offer.

Be careful out there.

Authentically yours,

Scott Brown

Downtown Brown Books, ABAA, IOBA

Many autograph authentication company’s issue letters of authenticity (LOAs), rather than certificates of authenticity (COAs), but collectors tend to call them COAs and I will too. James Spence Authentication (JSA), as an example, issues letters of authenticity that have unique certification numbers rather than letter numbers.

The deal for the company was so hot that the hedge fund and its investors had to pony up $850 million after originally agreeing to do the deal for $700 million. Lots of billionaire money is pouring into the collectibles industry. Collectors, the new parent company of PSA, has been on a buying spree, acquiring an auction house and another sports card grading company. The New York Times recently ran a story about the increasingly high-dollar competition for sports trading card companies [behind a paywall]. Billionaires have figured out that trading cards—which cost a few cents to manufacture—can be turned into tens of thousands of dollars by adding a fraction of a cent worth of ink from the pen of a star athlete. There may be no higher margin business. The authentication business, particularly certifying and encapsulating (slabbing) items, is also hugely lucrative, as the companies charge a percentage of the value of the object, which can be thousands of dollars per trading card, comic, and video game. Autographs are still charged only a flat rate because that’s how everyone does it. As soon as one of the firms changes to a percentage-of-value model for autographs, the others may well follow—it’s the same work, only it would be much more money.

If you go to JSA’s website to validate one of their COAs, the prompt offered is “Verify the validity of PSA & PSA/DNA certification numbers.” On the JSA site, visitors are invited to “Verify authenticity.”

Or perhaps someone whose first name begins with D.

Very few “celebrities” consider autograph collectors when signing items, which makes authentication inherently difficult. We all vary how we write all the time [I wrote about that here]. I found one example of Salinger signing a letter to a friend with his initials (which is a lot different from signing a book for a stranger) and “xx” for “love,” which is stylistically in the same ballpark as the Salinger book inscription I wrote about above.

As these initials suggest, Salinger was fond of printing rather than writing cursive. As he got older, his handwriting became a blend of printing and cursive, but I haven’t seen an example that is purely cursive like the book inscription attributed to him by PSA.

The same card collector on YouTube exposed faked signed Willie Mays cards which have problems with both the cards and the signatures, yet examples were certified by both PSA and CSG (also known as CGC—why so many three initial names in this field?). What his video also demonstrates is the amount of effort needed to closely compare authentic and forged items; signature authentication probably doesn’t cost enough to be done well by skilled (read: highly paid) professionals.

Searching Collectors’s (PSA’s parent company) LinkedIn page on March 2, 2024, for the term autograph turns up a person who lists their job title as “follower of Jesus Christ”, an “intermediate sales associate”, a “sales supervisor”, and one autograph “grader” (adjacent to authentication in the sports autograph field, related to how perfect the signature is on an artifact).

When I fly, I greatly appreciate the people who clean the planes between flights, especially when there’s a short turn-around time. I just don’t see how that prepares someone to separate real autographs from forgeries.

Stephen King has signed nearly 90 limited editions of his own books and probably as many anthologies. While some have small print runs, many were issued in hundreds and even as many as 2000 signed copies. That’s a lot of signatures.

JSA’s online certificate lookup provides limited information about the authenticated autograph. More information can be found on the LOAs themselves, including the date the item was submitted for authentication. I am assuming, I think reasonably, that consecutive LOA numbers, for items by the same signer, are highly likely to have been submitted by the same person.

I'm a forensic document analyst in Australia and I work mostly on authentication for government departments and insurers but also increasingly more private clients who are distrustful of the big TPAs. I think you are wrong about inscriptions. There are plenty of forgers who specialise in them, and also in faking provenance, which can be incredibly detailed. CoAs from the three big TPAs are also increasingly faked, which is an interesting new twist in the forgery game. This issue is entirely in the hands of collectors: they create the market and they can insist on proper reporting with evidence, or they can continue to pay CoA mills to tell them what they want to hear. I know what most people will chooose.

Saveafricanow used to be legit and I would see him at every book signing in NYC with bags of books for authors to sign. He eventually started being blacklisted at local bookstores because he would never actually buy any books from the local store hosting the signing and come in with twenty books that he bought elsewhere. His turn to forgery really seemed to get going when COVID hit and he could no longer get signatures in person but it also may have predated that time. It’s sad that eBay has not shut him down and he continues to sell forged autographs on the platform to uninformed buyers.