Backlist: Thoughts on Autograph Authentication, with Kurt Vonnegut forgeries as an example

First published in October 2022 on another platform

The first two useful ideas I ever got about authenticating signatures came from the great autograph dealer, Ken Rendell [I reviewed his memoir, Safe Guarding History here].

His first rule was don’t deal in autographs. Simple signatures simply cannot be confidently authenticated; that’s why he focused on letters and manuscripts.

Rendell’s second rule was that the question is not whether something IS authentic but whether it can be authenticATED. The example he gave me was this: You’re riding in the back seat of a care with Babe Ruth sitting next to you. You hand him a baseball and he signs it while the car flies down a bumpy country road. The resulting autograph is completely authentic—you saw the great baseball player sign it—but it cannot be authenticated because it won’t conform to any known real signatures.

By necessity, I have to buy and sell signed first editions, so I cannot apply rule one. Rendell’s second rule, however, has led me to focus on objective criteria that can be used to identify forgeries.

There is no way to authenticate any signature with 100% certainty. Even if you were there when the item was signed, you can’t pass that memory on to someone else. The best you can do is build up likely evidence, much like a jury does in court. The jury members didn’t witness the alleged crime, but they can decide whether one occurred, based on the totality of the evidence.

The first step for me is to consider whether an autograph is likely to be forged. This doesn’t establish whether any particular autograph is real, but it does rule out a lot of not-great forgeries, and most forgeries are not great.

Many people, dealers and collectors alike, seem to rely on someone else to do their signature authentication. Here’s a typical example. I gently suggested to a fellow bookseller that he might want to look more closely at a signed book he had for sale. He wrote back, “Please rest easy. This book was purchased from a reputable dealer and the signature is authentic.”

He didn’t make a case for why he thought the signature is real, he just offered an assurance that some other supposedly reputable dealer made the determination.

You can see how this reliance on others might be repeated endlessly—everyone buys from a reputable dealer or auction house and passes the authentication backwards down the chain of ownership until it’s impossible to say who decided the signature was real in the first place.

So in the interest of better approaches to autograph authentication, I’d like to pass on one technique I’ve found very useful. I’ll admit right up front that like almost all of my colleagues, I have no training in the field and that this is something I’ve come up with on my own.

My idea is simple:

Most signatures are a single line drawn in three dimensions.

Almost everyone signs their name very quickly. This is particularly true of people, like authors or other celebrities, who sign their name a lot. Their pen moves constantly, sometimes in contact with the paper and sometimes not.

The difference between applying ink to paper and not applying ink to paper is a tiny movement, often a fraction of a millimeter. With the slightest lifting of the pen point, the ink is no longer in contact with the paper. By paying attention to the spaces where the pen is not writing, one can learn a lot about how someone signs their name.

Most forgers master the individual parts of a signature separately. They start and stop between separate pen strokes, which aren’t really separate pen strokes. Again, it’s all one piece, just sometimes the pen applies ink to the paper.

Forgers often screw up these details because they can’t forge an entire signature in one go. Doing that is very hard. So it is often possible to find little tells, like a stroke starting from the left when the real signer’s pen should be moving right, for example.

If you want to better understand autographs, I recommend looking closely at the one you know best, your own.

Sign your name one time after another on a sheet of paper, making a column of signatures. Cover your previous signatures as you go with another sheet of paper so the visual cue of the previous signature won’t affect the way you sign.

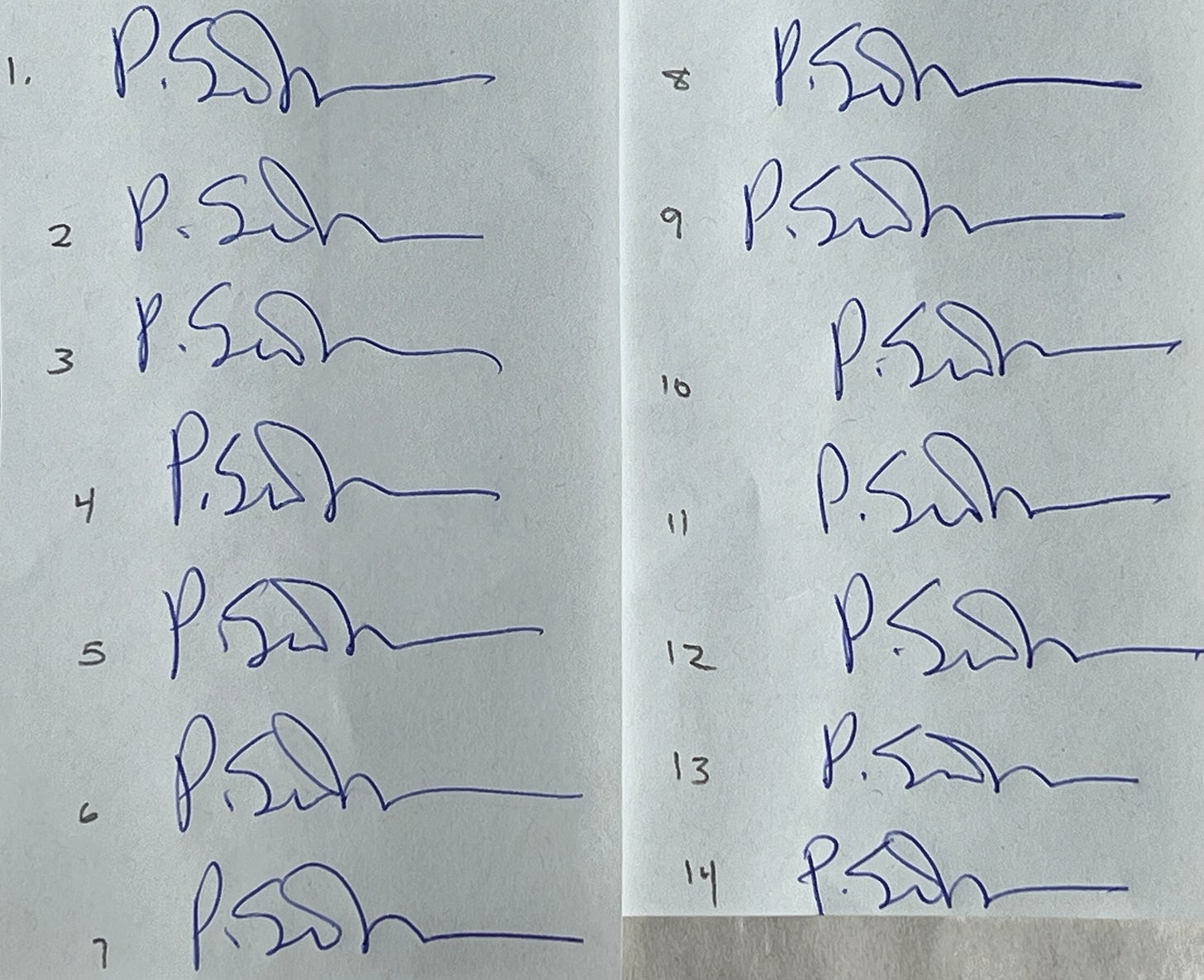

Here’s my signature times 14.

One odd characteristic of my signature, if I look at it as one I am attempting to authenticate, is the period between the P and the S.

It is a dot in example 1. It’s sort of an s in 2. It slants to the right in 4. To the left in 7. It looks like a tiny r in 12.

If you think of a signature as (in my case) three separate pen strokes (P + period + ScottBrown —the visible ones on the paper—the dot is very hard to explain.

But if you ask the question, how does this signature get from the P to the start of the S, it begins to make a lot of sense.

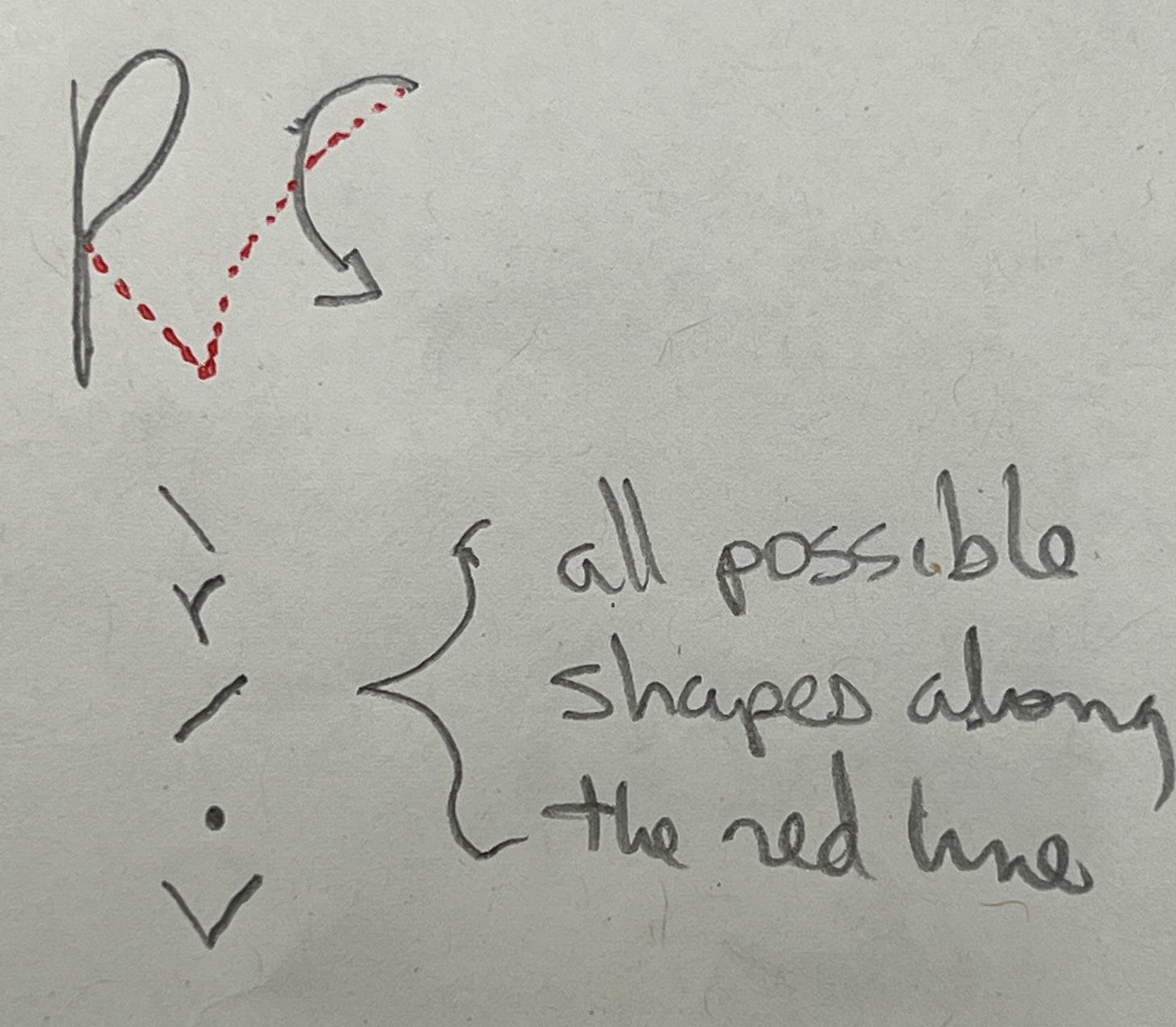

I’ve traced the path of my pen between the P and the S in red in this image.

My signature is moderately sloppy and so the point when my pen hits the paper for the period is not especially precise and as a result sometimes I’m early, resulting in a \ shape, as the pen descends down to the place where the period ought to be. Sometimes I’m late, resulting in a / . Sometimes the pen is in contact with the paper just before and after the lowest point of its travels, resulting in an r or even s shape. A V is also possible, even though there isn’t an example of it in the fourteen signatures in the photo.

To work out how a signature works above and on the paper may take a while. Often, it’s slightly sloppy signatures that provide the best clues. In signature 5 above, you can see the motion of the pen from the period to the top of the S as a faint squiggly line.

For example, from the P in number 5 alone, it’s hard to tell if I drew the first letter in two parts, a downstroke plus lifting my pen to start the loop at the top. But from no. 6 it’s obvious that I write the P without ever lifting the pen.

When I am trying to understand an autograph to determine whether I think one in front of me is real, I often work out a schematic of how the writer’s pen typically moves.

Try making a schematic from your own signature. Draw its basic shapes, showing when your pen leaves the paper. Also work out whether you make a loop or a v when your pen changes direction. The two shapes can collapse so they look almost identical, but with a V, your pen is always moving left to right and with a loop it goes back on itself.

In my signature, for example, the ttB structure where my first and last names blend into each other, has a definite loop at the end of the B (see no. 4). But sometimes (no. 2 and no. 3) it looks like a V. While the r in Brown is written as a v, a sharp point. Sometimes it is distinct (nos. 5 and 6) and sometimes it’s barely there (no. 3). But it’s never a loop.

The schematic for my signature would be something like this:

Applying These Principles to Kurt Vonnegut’s Signature

Up until the 1970s, Vonnegut usually signed his name Kurt Vonnegut Jr. After his father died, he dropped the Jr. I am going to focus on signatures without the Jr., because they are far more common and more commonly forged, although the principles can be applied to early signatures too.

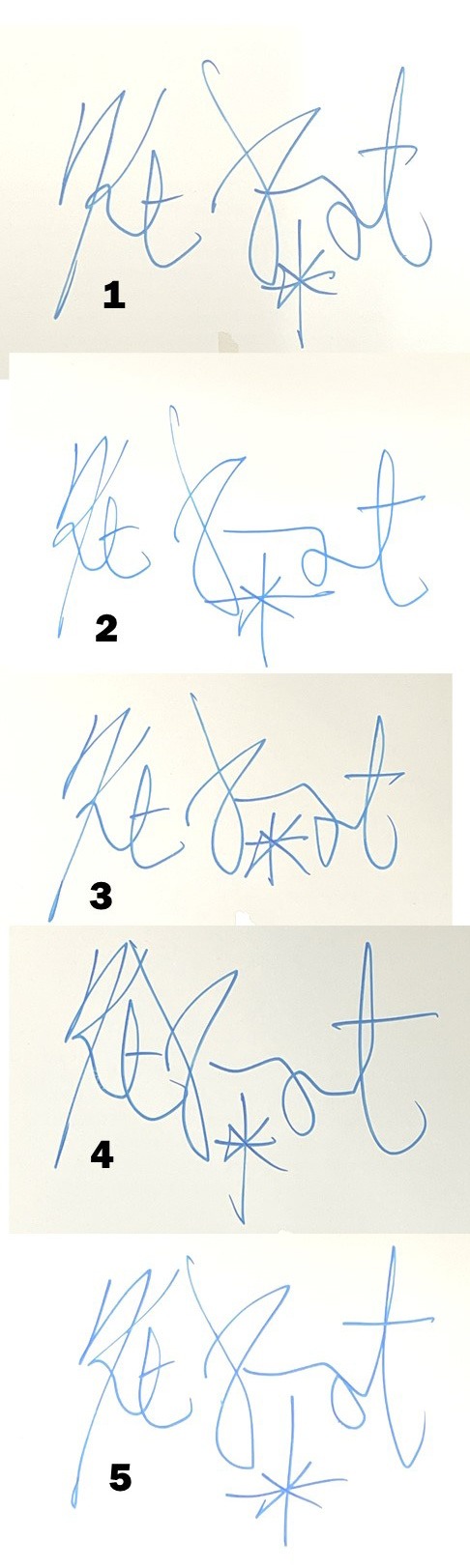

Here are five real Kurt Vonnegut signatures, all signed in copies of the same book at the same event.

If you look closely, you can find lots of variations:

a. In no. 4, his first and last name run together, while the others have space between them.

b. In nos. 1, 3, and 4, the “star” below Vonnegut has a triangle on the left side; the other two are made from lines that don’t connect.

c. In nos. 1 and 2, there is a loop at the center of the K. No. 3 might have a tiny loop. Nos. 4 and 5 have no loop at all.

d. In “Vonnegut”, the first character looks something like an upside down capital cursive S. it is followed by a horizontal line that becomes the g. In nos. 2, 4, and 5, the line does not touch the first character. In no. 3, it just touches. In no. 1, it fully crosses the first character.

etc.

To help understand how Vonnegut signed his name, I have broken the signature down into its component parts (for simplicity, I have left out the star, which Vonnegut sometimes omitted).

There are six separate pieces, which I have drawn above in time sequence, meaning first through sixth, without worrying about their spatial location. For example, the third stroke, the crossing of the t in Kurt, overlaps the second segment in the actual signature.

Now in red, I have added where Vonnegut’s pen was when it was slightly above the paper. This shows Vonnegut’s signature as a single motion, in three dimensions, both on and above the paper.

This is important because Vonnegut often signals this path as he is lifting his pen off the paper. Notice, in the five examples above, the “hook” at the top of the first character in “Vonnegut.” It points to the starting place of the second stroke. The bottom of the K also typically has a tight upward loop. Sometimes it loops to the right of the down stroke (nos. 1 and 2), sometimes it retraces the path of the down stroke (nos. 3 and 4), and once and a while, it loops to the left (no. 5).

These loops and hooks are very typical of Vonnegut signatures. They don't appear in the exact same spot each time because they are not intentional—Vonnegut was moving from one point of contact with the paper to another, lifting his pen a tiny fraction of an inch off the paper. Exactly how much he lifted and how fast govern the hooks and loops, and so there is variation, but very few authentic Vonnegut signatures don’t have any loops or hooks.

This way of looking at a Vonnegut autograph also explains a variation (not shown) that appears in 5 to 10% of his signatures: the horizontal cross in the t of Kurt connects directly with the first character in his last name. Vonnegut makes that motion every time, but every once and a while, he doesn’t quite get his pen off the paper and so the line in red in my schematic actually appears on the paper. The only difference between the regular and variant signatures is a minute change in the vertical position of the pen. It’s not a completely different signature.

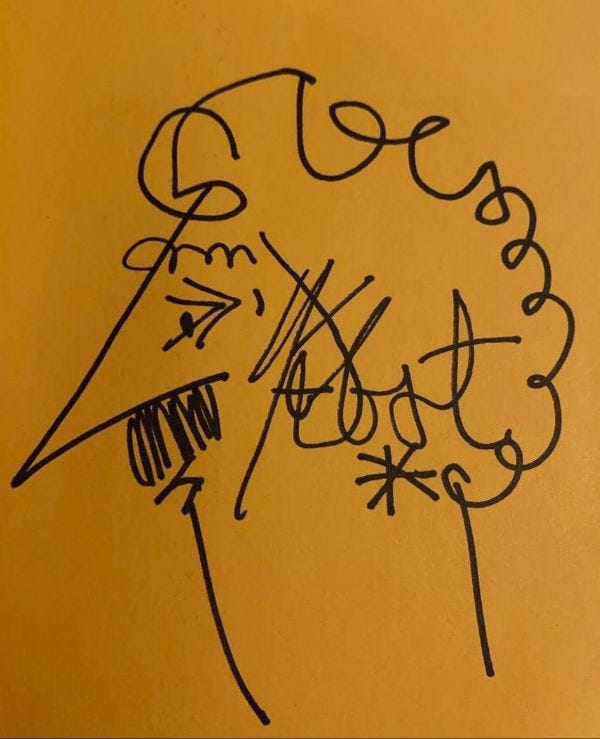

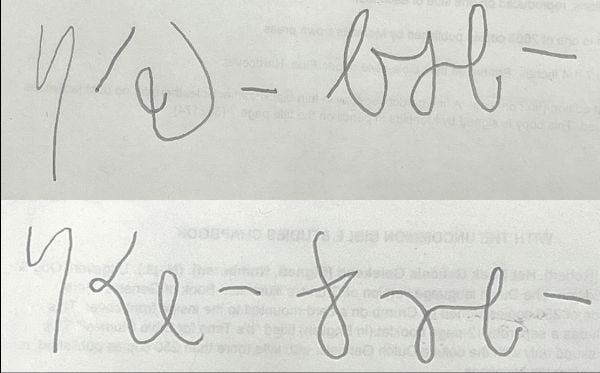

Now consider the signature that got me started with all of this. When I saw it online, I suggested the owner might want to look again. I was told I shouldn't worry because it came from a “reputable” dealer.

Don't be distracted by the self portrait. Look at the signature. On first glance, it does seem Vonnegut-like. It even has a hook at the base of the K. But DON'T BE DISTRACTED BY THE SELF-PORTRAIT.

I deconstructed the signature, putting the separate pieces next to each other (for reference, the real schematic is repeated below the portrait signature). The pieces are obviously wrong, even if the end result looks reasonably good.

In addition to the portrait pieces being wrong, try writing Vonnegut’s signature using those pieces. I won’t show it here, but it is very awkward to replicate the signature in the drawing in one fluid motion. The slanted down stroke of the K doesn’t really connect with the next piece. And the long vertical line that is part of the V in Vonnegut in the real signature, is part of Kurt in the portrait signature.

I would call the portrait a forgery, but in an upcoming book auction, the catalog description of one of the lots uses the word “spurious” to refer to a similarly questionable signature. I guess forgery sounds too harsh?

As a final exercise, consider the following Kurt Vonnegut signature, which sold recently at auction for $2375. The drawing is horrible—or should I say spurious (Kurt Vonnegut was an artist before he was a writer!)—but the signature makes even less sense than my previous example. (Among many problems, there are no hooks or loops at the end of the pen strokes. And consider the down stroke of the final t. The pen leaves a mark going further down. In real signatures, Vonnegut's pen makes a U-turn and heads for the cross bar of the t).

Be careful out there.