Why You Are Not Bill Gates's Bookseller

Thoughts on Kenneth Rendell's memoir, Safeguarding History

Why You Are Not Bill Gates’s Bookseller and Other Antiquarian Tales

Or, a review of Safeguarding History: Trailblazing Adventures Inside the Worlds of Collecting and Forging History by Kenneth W. Rendell

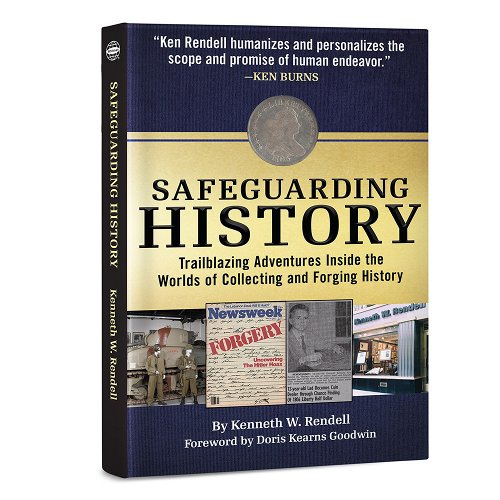

It would be fair to say that Ken Rendell was the leading dealer of historical letters and autographs of the last fifty years, but it might be more accurate to say that he created modern document collecting. Rendell traces the rise, peak, and gradual decline of the field in his fine new memoir, Safeguarding History.

I met Ken Rendell a few times back when I was the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine. In the early years of email, he liked to communicate by fax; in fact, I think his fax number was the only way I had to contact him. Back then he offered me a piece of advice that I still remember: It doesn’t matter if an autograph is real or not, the question is can it be authenticated? The example he gave went something like this:

You’re sitting in the back of Babe Ruth’s Packard limousine, barrelling down a dirt road. You hand him a ball and he signs it. The car is bouncing along. The signature is real but it cannot be authenticated because there aren't other balls signed in moving cars to compare it to.

Ever since, when I evaluate an autograph, I don’t ask, “Is this real?” Instead I try to make a factual case for authentication.

I didn’t know much of Rendell’s story at the time. I had read his book on forgery detection. I knew he was Bill Gates’s bookseller and that he had exposed several major autograph scams. After reading Safeguarding History, I realized that I had been looking at a hill without seeing the mountain behind it. I was completely unaware of much of Rendell’s Denali-sized career.

As fits the business memoir genre, the story begins with an inauspicious childhood. Rendell’s parents ran a failing drug store until his father died. Then his mother worked two jobs to make ends meet. Rendell earned his own money buying and selling coins starting when he was 10.

At an age when many children don’t fully understand the economics of their allowance, Rendell was traveling by himself to coin shows and putting out mail order lists. When he was in high school, he went with a friend to England to buy coins. While they were there, the Bank of England announced that the farthing, a coin worth about a quarter of a US cent, would be taken out of circulation. Rendell saw an opportunity, and he and his friend ended up acquiring six million of them, often below face value because banks didn’t want the hassle of turning them in.

Let me repeat that, in case you weren’t paying attention. In the late 1950s, a sixteen-year-old Boston high school student flew to London and bought 6,000,000 British coins (with a face value of about $17,500 at the time). By Rendell’s own account, no one in America collected farthings, and no one made the coin boards (the stiff paper folders with die-cut circles to hold coins) to put them in. That was no problem for young Ken. He convinced a manufacturer to begin making the boards and sold farthings in groups of one thousand. “It was a wild adventure, and 1959 came to a spectacular and profitable end!,” he writes (p. 17).

While still a teenager, Rendell also went to the Caribbean to search for rare date coins. By his own estimation, he and his employees (yes, he built a local staff) went through every coin at every bank in the Bahamas and Jamaica. He bought so many British coins that their prices in the US market began to drop precipitously.

Rendell’s coin business was growing rapidly. One day another coin dealer showed him a collection of letters signed by presidents, and Rendell immediately realized he was in the wrong business. He sold his coins and began buying documents and letters from the great men of history. There is deadpan humor in Rendell’s description of the questions that child prodigies face. “I felt tremendous guilt about giving up a lucrative coin business and going, at the age of 17, into a new field that might not be financially successful.” Most teenagers work dead-end jobs, if they work at all, and wait until midlife to have a career crisis. Rendell compressed that arc into his high school years.

Like most memoirs of successful dealers, the rest of the book goes from big deals to bigger deals and from rich collectors to richer collectors. Not since A. W. S. Rosenbach in the 1920s—Rendell’s bookselling hero—however, has any antiquarian been so much in the press. As the world’s leading autograph and document dealer, Rendell was the go-to expert in many high-stakes and high-profile forgery cases, including the supposed diaries of Adolf Hitler and Jack the Ripper, as well as manuscripts attributed to Elvis Presley. He appraised vast archives for litigious clients and testified about documents in the Mark Hoffman Mormon murder trial. You won’t be surprised that his arguments and methodologies prevailed in courts of law. One has to be both good and supremely confident to offer assessments of documents that will make headlines around the world or help send someone to prison for life.

Over the years, I have heard rumors about Rendell’s work with Bill and Melinda Gates, and the chapter devoted to them might be the one that appeals most to general readers. (An aside: as a bookseller, the chapter on appraising was the most eye-opening to me as some of the projects he worked on asked complex valuation questions that few professionals have ever seen or, I suspect, imagined).

About 1995, the Gateses commissioned Rendell to build a library for their under-construction home in Seattle. If you are wondering how Rendell got that gig, Safeguarding History will tell you. You will also come to understand that you wouldn’t have been up to the task. Never mind buying material on a near-industrial scale, the real problem was what to do with it once you had it.

Rendell hired six catalogers to describe it all. He employed a fleet of bookbinders to prepare matching cases with a bespoke design. He rented a warehouse and built a replica of the library to arrange the material in advance. He chartered a plane to fly the Gateses’s new library across the country; trucked it to the building site, craned the pallets in during a rainstorm, and reassembled the library quickly according to the meticulous arrangement worked out in the warehouse. Most mere mortals among dealers could never do a project that complex (Rendell credits his wife, Shirley Rendell, with many of the ideas that made the Gates library possible, so let me also add that you and your spouse together probably couldn’t handle a project that complex either).

Rendell was well-suited to his chosen profession. He liked reading the memoirs and biographies of businessmen to learn how their experience could apply to his own enterprise. He had a natural fascination for presidents and scientists and musicians. And he could think ahead and imagine what could sell in the future and didn’t limit himself to what was selling now. Rendell doesn’t draw this comparison, but I will. His way of thinking was similar to that of Steve Jobs, who once said, “Some people say give the customers what they want, but that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do.”

Something that Peter Howard, late of Serendipity Books in Berkeley once told me about Portland, Oregon, also applies to Ken Rendell. Peter said that Portland wasn’t a great book town. Powell’s City of Books made it a great book town. Rendell correctly sensed in the early 1960s that wealthy, successful entrepreneurs would want to surround themselves with the relics of other great men. He figured out what they wanted and how to present it, and he grew his autograph empire into an eight-figure business with operations on three continents.

In his spare time Rendell was a competitive skier. He retired in his forties because finishing second or third in races wasn’t good enough. “I went back to extreme helicopter skiing,” Rendell explains (p. 298), “and then in my 60s I focused on snowboarding.” If that’s not enough to make you feel tired, he was also single father to two sons, and he built three major personal collections, capped by a Second World War collection that now has its own museum.

Rendell attributes his prosperity to hard work (insanely hard work, in my opinion) and to being willing to meet customers where they are. He criticizes antiquarian booksellers as “appallingly condescending, even with me” and as men who act like “intellectual elitists” and “bibliographical snobs” (p. 161). Who could disagree? Rendell argues that he succeeded, in part, because he didn’t participate in the “self-created snobbism of the rare-book world.” He also refused to succumb to nostalgia about the good old days.

Like all good memoirs, Safeguarding History has its contradictions (“I am large, I contain multitudes,” as Walt Whitman wrote). Rendell criticizes dealers who were always looking back to an idealized past, but he can feel that way sometimes too. When he describes his decision to close his main gallery in Manhattan, he attributes it to an inability to “find out what was popular with visitors to the gallery. Our own success in selling was causing a concerning shortage of what was of interest to the general public.” In short, all the good stuff was gone (p. 240), a lament he heard and disdained in his younger days.

A more nuanced analysis might be that the collecting trend Rendell helped create had mostly run its course. I remember in the 1980s and 1990s seeing framed autographs, letters, and documents for sale in malls and tourist towns. Not so much anymore. The aesthetic of framed documents doesn’t fit with today’s home decorating styles. Of course, there are still lots of collectors of presidential autographs and important historical documents but they tend to have more modest goals than some of Rendell’s most acquisitive clients.

Safeguarding History also reflects the past in another way. If there were a Bechdel Test for autographs (a letter or document signed only by a woman), then just one of the fifty or so historical illustrations in Rendell’s book would pass, and that’s a document signed by Queen Elizabeth I (p. 148). By all accounts Elizabeth was a remarkable woman, but she was literally born into the role. (Melinda Gates gets two autograph illustrations in the book. Both times she signs alongside her husband, so they don’t meet the Bechdel criteria).

I am sure this very lopsided representation of who is important in history simply reflects the interests of most of Rendell’s customers. Still, not including examples of letters from Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Helen Keller (co-founder of the ACLU, among other things), Billie Holiday, Marie Curie, or any of dozens of other household-name women who changed history was a lost opportunity to help shape autograph collecting in the future.

Collectors and dealers in the book world can have very narrow interests sometimes. Focus is important, to be sure, but a broader understanding of the field doesn't hurt. Even if you don’t read many bookseller memoirs, Safeguarding History charts a life and business unlike any other in our part of the collecting world, and if you’ve read this far, you should read that book, too.