The Lost World of Small-Town Rare Book Shops

How a stranger's memoir perfectly captured my life selling antiquarian books

New List Today #125: Modern SF →. Still more books from the Tom Garner collection, plus additions.

A Tale of Two Bookstores

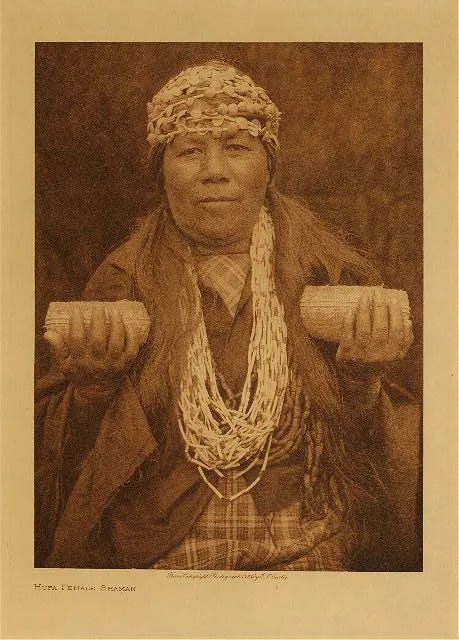

When I owned an open shop in far northwestern California, we scheduled a book-releated event each month for Eureka’s art walk, Arts Alive!1 One of our popular shows was an exhibit of plates from Edward Curtis’s North American Indian, an early 20th century work combining anthropology and photography. Curtis made reproductions of his photographs of Native Americans using the photogravure process, a kind of etching that produced prints with amazing contrast. At the time, I was very impressed with our Curtis show, and when I return to Humboldt County, California, I often see images we sold hanging on the walls of my friends.

Curtis’s work has grown more controversial over time and his relationships with his Native subjects wouldn’t pass muster today. After our Curtis show, a local institution consigned to me its copy of volume XIII of The North American Indian, which was devoted to the Indians of Humboldt County. The group’s board of directors decided that it could use the funds from the sale of this five-figure book to acquire more appropriate materials for their collection. While I understood that curatorial impulse, during the few months we had the book displayed in a glass countertop case, Hupas and Yuroks drove in from the reservations with their families to see their ancestors depicted in Curtis’s gravure prints.

I was reminded of that Curtis show while reading William Maxwell’s Booklegger: Anecdotal Recollections of a Skid Row Bookseller, because he writes about having plates from The North American Indian on exhibit in his Stockton bookshop. This was just the first of many parallels I would find between our bookselling lives.

Since I started writing these Dispatches from the Rare Book Trade, readers regularly ask when I’m going to write my memoirs. I’m flattered by the questions but not encouraged by them. By personality, I’m much more likely to write someone else’s biography than my own autobiography. Fortunately, I don’t need to write my memoirs because Maxwell effectively did, publishing a book that captures the essence of life as a small-town antiquarian shop owner.

Maxwell stumbled into the used book trade in the 1970s, about 15 years before I did, and he ran a series of shops in Stockton, California, until 2003, roughly a decade before I sold Eureka Books. The 625-mile distance between our locations didn’t affect our experiences. Both of our shops counted San Francisco as the nearest major city, and they both shared a particular cultural remoteness that shaped our operations.

The parallels between our bookselling lives accumulated as I read his book. Like Maxwell, I was drawn to acquiring entire collections. We both dealt in local history—Eureka Books could be counted on to sell at least 500 copies of most any new title on the Humboldt County region—and Maxwell’s chapter on selling antiquarian books about Stockton could be transplanted wholesale to Eureka with just a change of titles. And sometimes not even that much revision: We both sold copies of “Pen Pictures of the Garden World,” which an enterprising 19th-century publisher sold by subscription, swapping out Stockton for Eureka history in the main part of the text, depending on who ordered a copy.

We trod other identical bookselling paths. We both acquired copies of Hubert Howe Bancroft’s 39-volume Works from local institutions, and we each sold them at book fairs. We shared a similar experience with an impulsive collector and his private librarian, although in Maxwell’s case, he made the sale; in mine, the librarian sent the book back. Even the historian Ray Hillman appears in both our stories—Ray moved to Eureka from Stockton, bridging our two shops across time and geography.

What started as a collection of coincidences I see now as a portrait of a particular moment in American bookselling. In Booklegger, Maxwell captured the late 20th century bookselling experience in new-used-antiquarian shops in third-rate towns.

These shops had reputations that reached perhaps a few hundred miles and were entirely unknown beyond that distance. In fact, I have no memories of William Maxwell or his stores, although my extended family lives nearby in the Central Valley of California, and we seem to have been kindred bookselling spirits.

A few such stores still exist in larger cities—John King in Detroit and Brattle Book Shop in Boston come to mind—but they represent an era that has largely passed. (Eureka Books continues, though it has evolved under its new owner, shifting more toward new books in recent years.)

Maxwell writes with a direct, unvarnished style, and if you like book dealer memoirs, you’ll probably enjoy this one. My copy of Booklegger is already a second printing. Clearly I’m not alone in appreciating this chronicle of a vanishing kind of bookshop that was once found in many of America’s out-of-the-way places.

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

When I first moved to Eureka, I was part of the original founders of the Arts Alive! event. I appear just after the one-minute mark in this short video about it. I couldn’t watch it, but I look so young in the thumbnails.

Great memories of a wonderful spot.

Nice to see where my sister and brother-in-law lived and bought books, some of which I think I got: Alaska Bear Stories, for example.