Why are book descriptions so loooooooong?

Plus, a list of science fiction new arrivals along with a few incongruous photobooks

A list of new arrivals has just posted to my website. It was supposed to be a science fiction list, but some random other books like photography monographs and a couple of graphic novels snuck in.

Will Book Descriptions Keep Getting Longer?

I apologize for my part in the current arms race to see which bookseller can inflict the longest descriptions on their customers.

When I put out my second printed list, in February 1996, when my cutting-edge private email address was 75114.1153@compuserve.com and AbeBooks was not yet live, I could fit 82 items on three sheets of paper (six pages, 14 items per page). I included complete bibliographical citations for each listing, and I used few abbreviations. I never cared much for traditional book descriptions, like “16mo. 1/2 calf, sl fxd, sl rbd, but pretty, vg”1, so I spelled everything out.

The books on that list were mostly scarce then, and those titles remain scarce. A spot check suggests that no more than 20% of them could be purchased today on the Internet book marketplaces. Then as now, obscure books required some explaining, but space on the page was expensive. Each additional sheet added to production and mailing costs. I kept my red editor’s pencil sharp and pared the descriptions down to the minimum.

By contrast, my most recent “printed” list, produced as a PDF rather than as a published catalog, had one item per page. Of course, each page also had a picture, but even without the pictures, the text for 52 items runs to 13,000 words. The material in the list, mostly Japanese-Americana, was like my early Chicano lists in that the books also needed some explaining. Nevertheless, in 28 years, the number of items I can fit on a printed page has gone from 14 to just 1.

I am not alone.

The only bookseller whose catalogs I actively collect is Mark Hime of Biblioctopus. I have roughly half of his 64 printed catalogs. My collection of Biblioctopus catalogs begins with number two, from 1981. It is illustrated with photographs, some in color—a real expense for the early 1980s.

The list has 107 items, but many of the descriptions are for more than one book. I counted approximately 190 books listed for sale over 12 sheets (24 pages) of standard office paper. Roughly 8 books per page.

Biblioctopus’s recent catalog 64 is printed on 100 pages and had 102 items (not numbered, so I counted them for you, dear reader), a few of which are multi-book lots. Call it 110 items, or just over one item per page. Bibliopolis has gone from 8 items per page down to one per page in the Internet era.

These two examples are indicative of the general trend in antiquarian bookselling. Even auction houses have succumbed. In the Brinley sale, probably the greatest auction of Americana in the 19th century, the catalog required just 38 words to describe one the standard rarities, History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark (1814). One hundred years later, in 1981, Christie’s needed 118. Last year, Christie’s allocated 377 words to another copy of the same book (word counts based on the auction database on RareBookHub).

Mark Hime is pretty much the only book cataloger who is entertaining enough to justify the expansion of his descriptions.

The rest of us, I think, need to ask whether our logorrhea is really justified or if ever lengthening book descriptions are a textbook example of the tragedy of the commons.

In economics, the tragedy of the commons is what happens when people have unfettered access to a resource (in our example, basically unlimited space on the web for book descriptions): common spaces get overused to the point that the resource is ruined.

Individually, everyone has an incentive to make descriptions stand out by adding that one sentence that we booksellers hope will make the difference and a sale. The next year we have to add another sentence to keep up with our colleagues who all did the same. Descriptions keep growing, year after year, so far without end.

When everyone does it, the result is a torrent of words that no one can reasonably hope to do more than scan.

An enterprising bookseller could attempt to stand out in the forest of mushrooming book descriptions by writing good, short descriptions, following the writing advice of Elmore Leonard, “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.” Or by adhering to the maxims of William Strunk and E. B. White’s The Elements of Style, “Omit needless words.”

The reality is that writing less is harder than writing more. As the saying goes, “I would have written shorter, but I didn’t have the time.”

So, unfortunately, we booksellers are likely to continue expanding our descriptions in the hope, I suppose, that our mostly indifferent prose and photos will look important and impressive, even if we know, in our heart of hearts, that no one actually reads all the text.

—Scott Brown

*

Stolen Stuff Stays Stolen

A painting stolen in 1969 turned up in a Utah estate a couple of years ago. A court just returned it to the 96-year-old son of the original owners. While there is a statute of limitations on the crime of theft, stolen goods stay stolen basically forever.

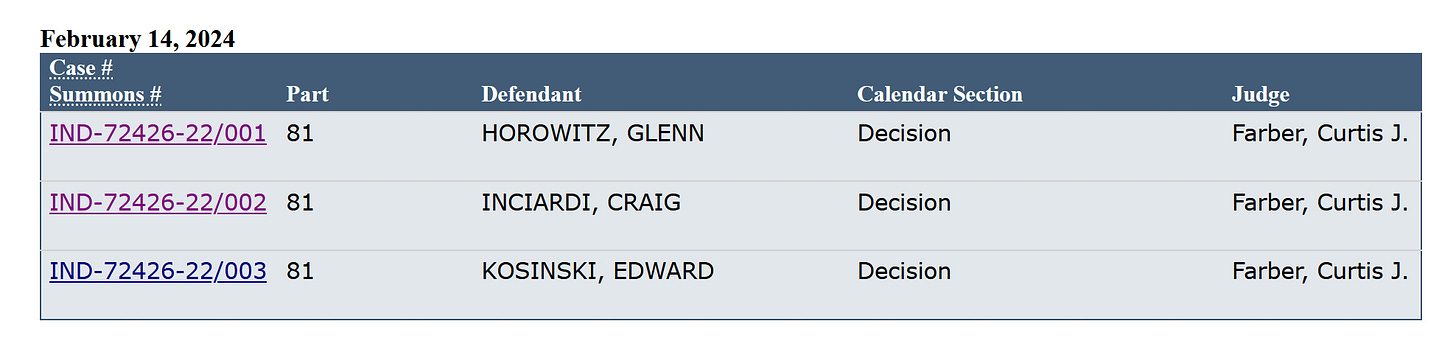

In part, this idea is behind the charges faced by the bookseller Glenn Horowitz, of New York, who is basically accused of covering up a 30-year-old theft of original Eagles song lyrics. Sources tell me that a news article about the case is in the works, probably to be published about the time his trial was scheduled to start (February 14). The judge’s calendar no longer shows a trial, but has that day set aside for a hearing of some sort.

I don’t know what is going to happen, but you can read my initial take on the case, which I recently moved to Substack along with a few other older essays that I thought were worth preserving.

An actual book description from a list published in 1984. Pretty typical of the era. The description “16mo. 1/2 calf, sl fxd, sl rbd, but pretty, vg” translates into English as “Sextodecimo format (about 4 by 6 inches). Bound in half-calf. Slightly foxed, slightly rubbed, but pretty. Very good overall.”