Tracking Forged Cormac McCarthy Proofs Around the World

How a single text message led me to fake books on three continents

My guide to identifying Cormac McCarthy Proof forgeries can be found here: https://downtownbrown.substack.com/p/cormac-mccarthys-early-proofs-real-and-fake

This is the story of how the forged Cormac McCarthy proofs came to light.

The Cormac McCarthy Capers

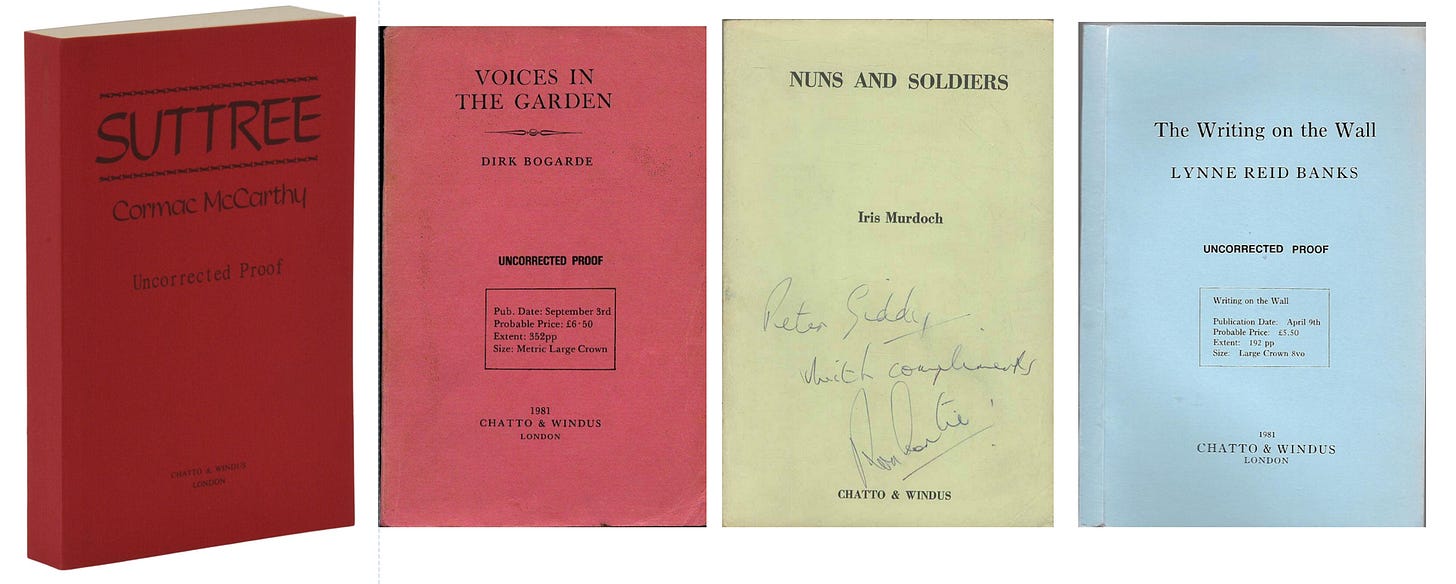

A couple of weeks ago, Rachel Phillips of Burnside Rare Books here in Portland generated an international response when she posted a British proof of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree1 to her website. The asking price was $4,500.2

The international response, by itself, wasn’t that unusual. Rachel, with her partner Roger Hucek, are among the top dealers in 20th-century first editions, and they regularly offer unbelievable material.

In this case, however, the book in question was beyond belief because no proofs of the UK edition of Suttree were commissioned by the publisher.

Proofs3 are made by publishers in small numbers prior to the first printing of a book. They are almost always paperbacks and many of them, particularly before the late 1980s, are unadorned and look cheaply made.4 As part of the publishing process that the public isn’t supposed to see, proofs can be catnip for collectors, especially Cormac McCarthy collectors.

Rachel learned that her Suttree was a forgery from Umberto La Rocca5, a major collector of Cormac McCarthy based in Italy. Rachel sent me a text message with a photograph of the proof and asked my opinion. In my usual off-the-cuff way, I immediately texted back, “definitely fake.”

Readers may reasonably doubt the assertions about forgeries made in this essay. For the sake of those of you who are willing to give me the benefit of the doubt, I have relegated my evidence in excessive detail to a companion bibliography.

Like most people, I am prone to snap judgments. But ever since I read Thinking, Fast and Slow by the Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman, who died very recently, I try to be more self-aware. Fast thinking can be right, built up from long experience (which is how we can drive a car at 70 m.p.h. while having a conversation). It can also be wrong, the result of the human brain’s habit of substituting an easy question for a hard one.

Kanheman’s research suggests that our brains are fundamentally lazy and look for easy answers. In the book collecting world, we must all be wary of substitution when it comes to authentication. We are hardwired, it seems, to substitute the hard question, How do I know this is real? with the easy question, Do I trust my source?

When I consider whether something is real or fake, I try to think slow, remembering Kahnemann’s lesson, and ask the hard question. My gut instinct about the Suttree proof was that there was something wrong with the cover. That observation was easier to make because Rachel introduced the possibility that it was fake to me at the start. If I had just seen the proof on a table, it might not have entered my mind that it could be a fabrication. In 30 years of bookselling, I don’t think I have ever seen an entirely invented book.

Looking at Rachel’s Suttree in this light, I immediately noticed that the cover incorporated the design of the title page. The covers of proofs are usually plain text. A few minutes searching the internet produced images that looked like I expected.

As readers of this newsletter already know, I love a poking around in the true-crime corners of the book world. My hot-take about Burnside Rare Books’s Suttree steered me to sham Cormac McCarthy proofs that have spread to three continents, fooling dealers, auctioneers, and collectors for years. I found images of deceptive McCarthy proofs on the website of a London book auction house and on a Reddit forum. Checking with collectors and booksellers led to still more fake McCarthy proofs.

Rachel told me she returned the proof to the seller, an Australian dealer on Biblio.com. I figured that meant BooksCurious in Canberra, who has more rare McCarthy books for sale than anyone else Down Under.

I sent an email, and Mark Warner responded. He graciously filled in the rest of the story.

Mark told me that after receiving Rachel’s return request that he, too, wanted a second opinion. So he emailed the person that he considered to be the leading expert on Cormac McCarthy proofs. That person happened to be Umberto La Rocca, who had started the three-continent email chain in the first place.

Mark told me he had obtained the proof of Suttree a few years ago from Paul Ford, the co-author of a 2013 self-published Cormac McCarthy bibliography. Paul told Mark that he got the proof from his co-author, Stephen Pastore. “While they were both searching around for McCarthy items to include in the book,” Mark explained, “Pastore came up with a few UK proofs that were later sold to collectors for large amounts.”

Paul Ford agreed to take the proof copy of Suttree back and refunded Mark’s money. (Other sources tell me that Ford also issued refunds for at least two other fake proofs acquired from Pastore and that Pastore sold another fake proof to a dealer in 2012).

Such is the small world of top Cormac McCarthy dealers and collectors. They all seem to know each other. Many of them also blur the line between collector and dealer. La Rocca told me that he wasn’t a bookseller but that he had done “very well” selling McCarthy books. Ford has collected McCarthy for several decades and sells books on the side. Mark Warner collects McCarthy and periodically offers books from his collection for sale on Biblio.com.

Serious collectors of Cormac McCarthy have always faced the problem that he wrote relatively few books, often spaced years apart. Over a six-decade career, his output was just 12 novels, including two published shortly before he died in 2023 at 89.6

Of those books, only the first five, The Orchard Keeper (1965), Outer Dark (1968), Child of God (1975), Suttree (1979), and Blood Meridian (1985) pose any difficulties for collectors. None of them sold more than a few thousand copies in the US or in the United Kingdom. McCarthy’s sixth book, All the Pretty Horses (1992), had a first printing larger than the total sales of the five previous novels added together, and it became a bestseller. McCarthy’s subsequent books had print runs of tens or even hundreds of thousands of copies, and they are all easy to find in the first edition.

Yet despite McCarthy’s small output of books, La Rocca told me that his collection included some 200 items.

The intense demand for McCarthy’s books around the world combined with the relatively small number of collectible items has driven prices up. It has also also pushed collectors to pursue British editions and proofs of all kinds. After all, if you are going to be a collector, you need some things to collect.

In McCarthy’s case, adding proofs to a collector’s want list doesn’t help that much. No proofs were issued for his novel Outer Dark and no British proofs exist for three of the five sought-after early novels. Whenever collector demand exceeds the available supply, you can be confident that unscrupulous people will resort to forgery to fill it.

Most book-related forgeries are autographs, but someone went a step beyond and invented examples of all the nonexistent Cormac McCarthy proofs and imitations of several that do exist. Faking entire books is not unprecedented, but it doesn’t happen very often. The once respected bibliographer Thomas J. Wise faked chapbooks by noted 19th century writers, beginning in the 1890s. More recently, Marino Massimo de Caro, an Italian raconteur, forged early Galileo pamphlets, and an unknown gang of Georgian thieves has been stealing rare Russian first editions from the libraries of Europe, replacing them with forgeries convincing enough to allow the criminals to escape with the real copies of Puskin and Gogol.

Few collectors, dealers, or librarians are on the lookout for such bold deceptions. I asked Glenn Horowitz, the bookseller who brokered the $2 million sale of Cormac McCarthy’s manuscripts to Texas State University, about the fake McCarthy proofs.

“How bizarre,” he wrote me in an email. “Why would anyone endeavor to undertake such a forgery?” Money, of course, is part of the answer, but one also senses a certain element of braggadocio—of putting one over on the experts who believed the fake books.7

The forger initially fooled the Italian collector Umberto La Rocca, who told me he had purchased a fake copy of the Suttree proof. Forged proofs also ended up in the library of the Irish collector Philip Murray. His McCarthy collection was sold at auction in 2019 by the prominent Dublin-area firm Fonsie Mealy, which did not notice fake proofs of the UK editions of Outer Dark, Child of God, and Suttree (and possibly The Orchard Keeper, too) among his books. The bookseller who bought them at the Murray sale didn’t realize they were fakes, nor did Forum Auctions, which resold two of them for £1,500 ($1,900) in late 2023. The collector who owns the other two Murray proofs told me, “I hope that they are genuine.” (Suttree, at least, is almost certainly fake)

That’s a lot of experienced book people overlooking a good-sized stack of forgeries.

When I inquired about forged and potentially forged proofs, in almost every case the reply I received was about the provenance of the book—the story about where it came from.

Forum Auctions’s email to me was typical. “These proofs were consigned by a dealer who bought them from the collection of Dr Philip Murray in 2019.8 I would be surprised if they were shown to be wrong as Murray and McCarthy were friends.”

This would appear to be a classic example of Kahneman’s idea of substitution. In ordinary situations, few book specialists would argue that knowing an author automatically makes one an authority on their uncorrected proofs, but our brains will go there when asked a hard question about authenticity.9

In the end, the final lesson of these forged Cormac McCarthy proofs is to remember the mantra look at the book. In most case, the physical book will tell you everything you need to know. As I detail in my analysis of the proofs, the forgeries use desktop printing, ill-matching paper, clumsy binding, and often ahistorical cover designs. Once you know what to look for, they are easy to spot. It’s figuring out what to look for that is hard.

A forger was able to pass off fake proofs because collectors wanted them to be real, and several of them came from the authors of a McCarthy bibliography. This encouraged buyers to substitute the hard question of determining authenticity with the simple fact that they came from the experts who, as one person put it to me, “literally wrote a book on it.”10

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

You can read my analysis of the forgeries here.

While working on this Dispatch from the Rare Book Trade, the people I talked to referred to this book as Soo-tree and as Suh-tree. In the novel, the title character is sometimes called “Sut”, which favors the latter. The correct pronunciation also intrigued Cormac McCarthy’s first serious collector, the bookseller and bibliographer J. Howard Woolmer, who began collecting McCarthy’s works in 1969. Woolmer and McCarthy enjoyed a long correspondence, including a pair of letters written in 1989 in which Woolmer asked McCarthy about the pronunciation of the book’s title on August 22. McCarthy answered on September 6, “It never occurred to me that folks would pronounce Suttree to rhyme with shoe tree but they do.”

One dealer told me that $4,500 was on the low side, “if it had been real.” That judgement was borne out while I was working on this story. Rachel bought and then sold for $7,500 a British proof (real this time) of McCarthy’s magnum opus Blood Meridian. From acquisition to sale took about two weeks.

For simplicity in this Dispatch, I’m going to refer to prepublication paperbacks as proofs. They are variously called proofs, uncorrected proofs, advance reading copies, bound galleys, galley proofs, etc. and these terms can be somewhat interchangeable, depending on who you ask. If you want more information about this topic, the bookseller Ken Lopez wrote an essay on proofs that can be found on his website [permalink].

“Cheaply made” is a metaphorical rather than a literal statement. Proofs are, in fact, expensive to produce, costing far more per copy than the finished books. Prior to the late 1980s or early 1990s, when color printing for the covers and good-quality short run paperback bindings became affordable, proofs looked inexpensive.

Umberto La Rocca, who lives in Italy, has probably done more work on the publication history of Cormac McCarthy’s books than anyone else. When I emailed him during my research for this essay he called me back from San Marcos, Texas, where he was spending several days in the Cormac McCarthy archives there. He has also visited the Andre Deutsch archives in Tulsa (he reports that the McCarthy folders in Oklahoma are inexplicably empty) and the Chatto & Windus archives at the University of Reading.

McCarthy also had two plays and two screenplays published almost as curiosities. A forged proof exists for at least one of those books, the UK edition of The Stonemason.

A person who saw a number of fake McCarthy proofs in the early 2010s said he thought they were directly inspired by the forgeries of Thomas Wise a century before. A number of forged McCarthy proofs, he said, were sold on AbeBooks by a seller named “Carson Ottley.” Thomas J. Wise invented the firm Ottley, Landon & Co. to be the publisher of some of his forged pamphlets.

The actual email from the auctioneer gave the year as 2016. The first sale of books from Philip Murray’s book collection was in 2016, but the McCarthy books were sold in 2019, after Murray died.

This experience induced me to add the note “forgery” to one of the signed books in my personal collection. I am keeping the book because the book itself is scarce and I don’t have another copy. Without the notation of the signature’s dubious nature, I can imagine someone in the future accepting the signature as real because it was in my collection.

Many people helped with this essay, providing photographs, history, background, and information about Cormac McCarthy and his books, both real and fake. The conclusions and any errors are my own. I would particularly like to thank Brendan Devlin, Paul Ford, Max Hasler, Umberto La Rocca, Ken Lopez, Sean Lynch, Rachel Phillips, Kevin Sell, and Mark Warner for their assistance.