Just posted to DowntownBrownBooks.com → List 128, more books from the Tom Garner collection, including Tony Hillerman, James Lee Burke, James Crumley, and John Gardner.

My wife just finished reading Edward Gorey’s biography, Born to Be Posthumous. She has started illustrating the books she writes and has naturally become interested in other author-illustrators. Since I’m a bookseller, whenever writers from an earlier generation come into our conversations, I tend to check out the current market for their first editions.

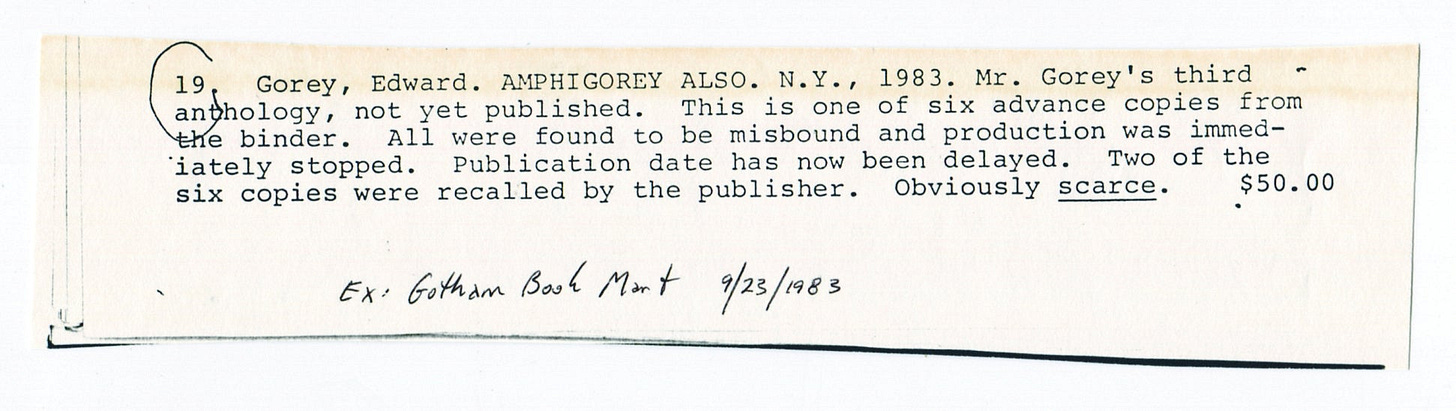

That’s how I stumbled upon a fascinating listing for a rare variant for Gorey’s 1983 anthology Amphigorey Also—a nice follow up to last week’s Dispatch about issues vs. states. The description explained the origin of this rarity:

One of six advance copies misbound by the publisher in decorated paper over boards (instead of decorated cloth); production was immediately stopped and publication was delayed. The publisher recalled two of the copies, the other four apparently circulated before they were recalled.

Another bookseller offering a copy of the book presented an alternate account, a protoypical example of how stories evolve over time from the fact of scarcity to an invented explanation:

The publisher pulped virtually all issues since it was to be issued in cloth instead of paper covered boards. A handful of copies got out before the printed copies were withdrawn and pulped.

Such are the dreams of bibliophiles. The small difference in the binding of the book, which most people wouldn’t even notice, makes a 30-fold difference in the price. Other than a fire in a warehouse, nothing gets the collector’s heart pounding like the phrases “stop the presses” or “destroy the print run.” How exciting.

I have a rule of thumb: Any story about a book’s rarity that includes specific numbers is probably made up. Commercial publishers don’t generally track the minute details that book collectors obsess over decades later.

A corollary to this rule: The more a story about a book appeals to your collecting instincts, the less likely it is to be true. Stories get better over time but rarely more accurate.

There are always exceptions that prove the rules, and Amphigorey Also is one of them. It tells us a lot about why true variants are very uncommon in modern first edition collecting. We’re centuries away from the romantic era of hand-cranked presses. The notion that publishers can stop production once it starts has been out of date for a very long time.

But if you have a mishmash of the hand-press era of printing and modern factories in your head, a phrase like “production was immediately stopped” conveys images of a supervisor hitting a red emergency button followed by ringing bells and the collective groan of machines grinding to a halt.

The reality of book manufacturing is decidedly less exciting than that.

This video about how books are made, from the Book Manufacturers’ Institute, is wonderfully boring1 and therefore perfect. It’s easy to see how unlikely it is for this process to be stopped to make a last minute change.

Publishing, the business of discovering authors and promoting their books, is still centered in Manhattan, but the actual printing and binding of books left the island long ago. First to the boroughs, then to the Midwest, and eventually to Asia. A lot of people in publishing in New York have never even set foot in a printing plant, let alone ordered the machines to stop.

When I first started Fine Books & Collections magazine, I’d sometimes visit our printer to watch the sheets roll off the press. We ordered small runs—just one or two thousand copies of each issue. A big cost was paper because it took about a thousand copies just to get the press warmed up. That’s right—the first thousand sets of sheets went straight to recycling. Once the ink was flowing, the machine was so fast you couldn’t see the individual pages.

Fifty years ago, Americans bought about 200,000,000 new print books. Today we buy about a billion (yes 1,000,000,000). To keep up with that demand, book manufacturing has had to be fast and get faster. Combine that with the geographic separation of publishing and printing, and you can see why “stop the presses” changes are rare.

So how did just six copies of Amphigorey Also end up bound in a different material than the final book? It turns out that we know the answer because the world of Gorey collecting met the publishing industry while the books were still being made. That kind of connection almost never happens.

The legendary New York antiquarian shop Gotham Book Mart obtained a copy (or copies) and offered the variant Amphigorey Also in a catalog before the book’s publication date.

Andreas Brown, the second owner of Gotham Book Mart (after the legendary Frances Steloff), was a tireless champion of Edward Gorey. He came up with the idea for the Amphigorey anthologies, which combined many of Gorey’s small, odd books into single volumes, and he convinced G. P. Putnam’s to publish the first one. The success of that book and its sequels helped give Gorey financial stability as a working artist. “Frankly, I’d be lost without the Gotham Book Mart,” Gorey once said. For the rest of his life, Gorey and Gotham Book Mart collaborated on limited editions of his books.

So it’s not entirely surprising that someone working at the publishing house thought the misbound copies of Gorey’s forthcoming book would be collectible and slipped them to Gotham Book Mart.

But what, exactly are these copies. Gotham called them “advance copies from the binder.” Over time, this has been shortened to “advance copies”, a term usually used for books sent out to reviewers and bookstores. Maybe that’s what Gotham meant. Or maybe they were trial bindings—sample copies for final approval. Six of those would be entirely normal.

For some reason, the publisher wasn’t happy with the samples and stopped production. This wasn’t a “stop the presses” moment. It was a “don’t start the presses quite yet” situation, which happens from time to time in publishing.2 It’s also possible that such occurrences were more likely at Gorey’s publisher, the startup Congdon and Weed which was destined for bankruptcy in just two years. The logistics of manufacturing books are complex and hard to master. Most printers are scheduled well in advance. If you make a last minute change, you lose your place in line. Gorey’s publication date slipped.

Here’s what I still can’t figure out in the Gotham catalog copy: “Two of six copies were recalled by the publisher.”

If they were “advance” copies sent to reviewers, why bother recalling them? Advance copies are not expected to be final and besides, these books did not have dust jackets, which seems like a bigger deficiency than whatever was found wanting in the binding material.

And then there’s the question of the Gotham copy itself, which was presumably among the four that “escaped.” It seems unlikely that someone outside the publishing house received one, got the full scoop on what happened along with a request to return it, and then decided to sell it and the backstory to Gotham Book Mart anyway. I’d put money on the scenario that someone inside the publishing house quietly handed off four copies to Gotham.

As for whether these copies represent states or issues of the first edition, I’d say neither. There’s no evidence that they were ever offered for sale to the public, except as collectibles before the publication date. That makes them either advance copies (a hardcover advance reading copy [ARC], if you will) or trial copies from the book design process. Not technically first editions, but certainly desirable for a Gorey collection.

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

A bit of political commentary. With all the discussion about tariffs and bringing manufacturing jobs back to the US, it’s useful to look at the workers in this video, many of whom look insanely bored by their repetitive jobs loading machines or moving books from one conveyor system to another. And since as a country we’ve turned against immigrant labor and the unemployment rate is very low, it’s not clear who, exactly, would work in American book manufacturing plants if printing jobs moved from China back to Michigan.

Or it could have been a “stop the binding machines” moment, if the sheets had already been printing.

Thank you for this thoughtful and exacting entry.

As always, highly entertaining and informative. Thank you Scott.