A Collector's Quest for the Books that Made Jane Austen

Bookseller Rebecca Romney Resurrects the Stories Behind Pride and Prejudice

New Catalog Today

Comic books pervade popular culture, extending even into literary fiction, like the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. Yet, graphic novels, the book form of sequential art, where the stories are most widely read, don’t get much love from book dealers. More than 60 graphic novels are included on Downtown Brown Books’s new arrivals list today.

On Jane Austen’s Bookshelf

Rebecca Romney, one of the best known rare-book dealers, is a reluctant social media star.

With more than 400,000 followers spread among Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook, plus endless reruns of her book appraisals on Pawn Stars, and now a new book exploring Jane Austen’s literary influences, she maintains a high profile despite being “temperamentally not suited to social media.” She continues these public-facing roles because she wants to introduce people to book collecting. “Books were personally transformative for me,” she said, “and that’s the motivation for me to bring people in.”

But this public-facing work comes at a cost. “The more people interact with you on social media, the more dispiriting it is,” Romney told me in a recent phone interview. Periodically, she has to take a break and “cycle out the toxicity” before she can return to posting. For her, as one of a small number of prominent women in the rare book trade, a single post can generate “three hundred digital catcalls at once.” Unless you've experienced that directly, she said, it’s very hard to know what it’s like.1

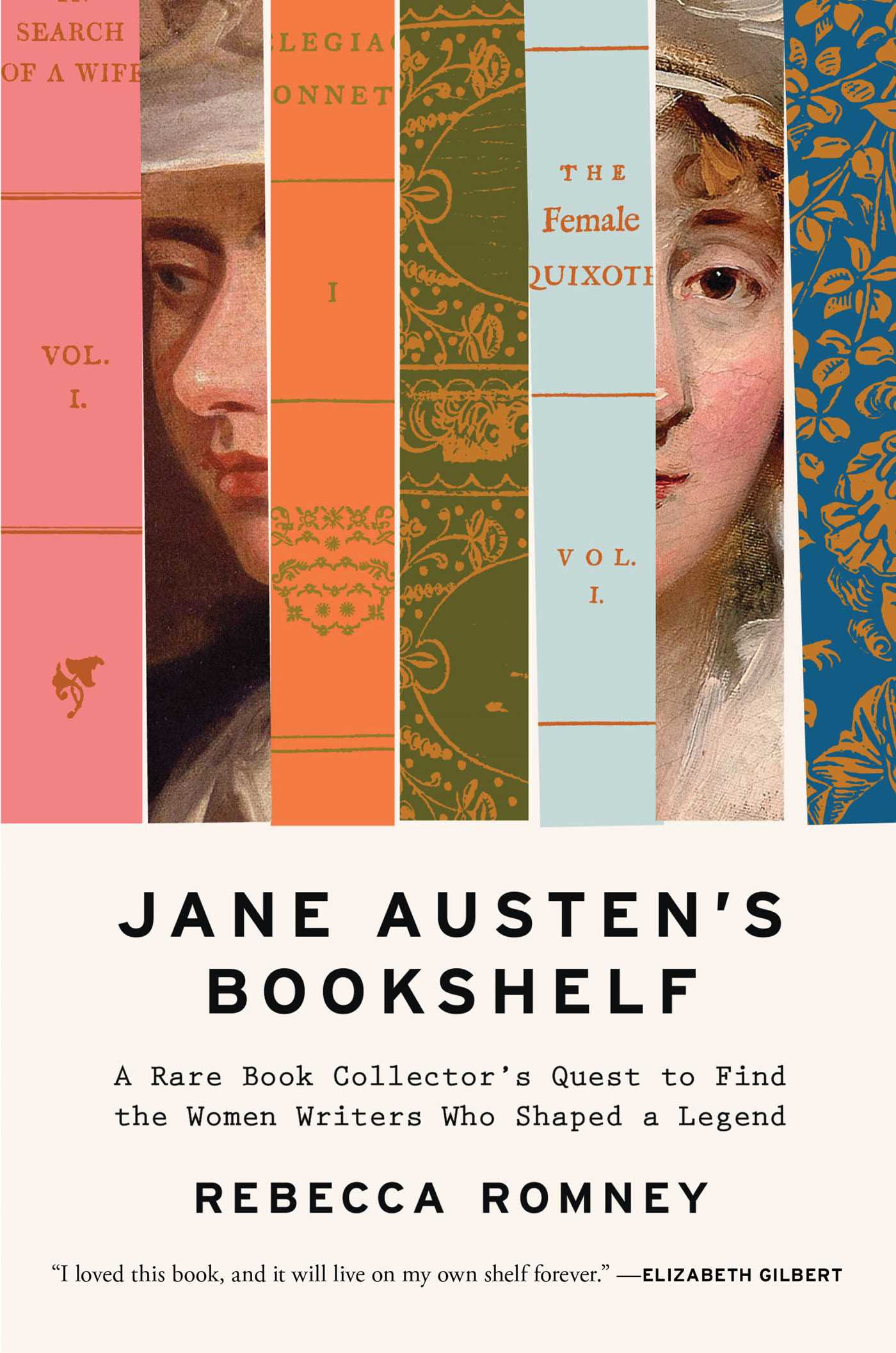

Romney’s latest effort to expand the universe of book collectors, Jane Austen’s Bookshelf: A Rare Book Collector's Quest to Find the Women Writers Who Shaped a Legend, doesn’t fit neatly into a single genre—it is part bookseller memoir, part book history, part collecting memoir, and part literary criticism. It can also be read as an instruction manual for how to start collecting, beginning from a passion for reading and progressing to acquiring special copies of books to memorialize the experience.

The very idea of the book demonstrates how a collection can grow in unexpected ways. Romney’s exploration of the writers who influenced Jane Austen began with learning that the phrase “pride and prejudice” originated in the novel Cecilia by Frances Burney. Despite being a lifelong Austen reader and an experienced rare book dealer, Romney had somehow missed that Burney was one of Austen’s favorite authors. This revelation led to others, as she began noticing references to other women writers throughout Austen’s works, like the enthusiastic praise of Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho in Northanger Abbey and the staging of Elizabeth Inchbald’s play Lovers’ Vows" in Mansfield Park. Romney’s close reading of Austen led her to collecting Austen’s sources and ultimately to writing a book on eight writers who influenced the author of Pride and Prejudice: Burney, Radcliffe, Inchbald, Charlotte Smith, Charlotte Lennox, Hannah More, Hester Piozzi, and Maria Edgeworth.

The writers are all women because Austen’s male influences have been widely written about. The women, who are studied now in academic settings, have not filtered as much into the standard references that collectors and dealers rely upon or into the general awareness of book collectors.

Jane Austen’s Bookshelf may be the first feminist bookseller memoir. Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern, two chroniclers of the rare book trade in the twentieth century, faced many obstacles that they tended to brush off, like their dismissal of the Grolier Club’s original male-bibliophiles-only membership policy as merely “irksome.” Romney provides many examples of scholars and dealers describing her eight authors in terms of the men they knew and not the books they wrote.

When I asked about the feminist themes in her book, Romney explained that it wasn’t a conscious decision. She simply aimed to be “open and accurate”—and being open and accurate meant being feminist. The critic William Hazlitt's observation about Frances Burney could apply to Romney and Jane Austen's Bookshelf: she “is a quick, lively, and accurate observer of persons and things; but she always looks at them with a consciousness of her sex.”2

Like most booksellers who don’t have relatives in the business, Romney’s path to becoming a rare book dealer was accidental. “I was just a girl from Idaho with a fairly undistinguished academic career,” she said. Against any reasonable chance of success, she applied to work at Bauman Rare Books, the largest antiquarian dealer in the country.3 They hired her and changed the course of her life. She learned not just about rare books but also about the importance of finding new collectors, a mission she continues to pursue.

The transition from Bauman to Type Punch Matrix, Romney’s innovative rare book venture founded in 2019 with bookseller Brian Cassidy, required careful planning. “I could not afford, ever, a career bookselling that did not fully support me and my two children. I knew I couldn’t leave a salaried position until I could hit the ground running.” This was particularly challenging because, as she noted, “In most cases bookselling endeavors won’t support a living wage for a long time.”

Romney’s pragmatism about providing for her family shapes her view of book collecting as well. As a collector, she seldom spends more than a few hundred dollars on a book, leading her to buy later printings or editions with appealing covers or interesting introductions if a first edition is personally unaffordable—she reserves her high dollar acquisitions for Type Punch Matrix. It’s a more holistic approach than most antiquarian booksellers would suggest to their customers.

While offering anecdotes from her life as a dealer and a collector, Romney’s fine new book also explores the academic literature about her authors and traces how each of the writers gradually faded from the English literary canon. “I am doing this very much avocationally,” Romney said, explaining her venture into the territory of professional scholars.4 Jane Austen’s Bookshelf “is not for English professors. It’s for readers. They are reading as a hobby… You don’t have to be a rare book dealer in order to collect. You don’t have to be an English professor to read avocationally.”

In addition to offering a model approach for collectors, Romney also aims to do something else good booksellers do: shape the market for rare books. “Booksellers play an editorial role,” she said, showing collectors what is interesting. “We are often invisible editors and tastemakers.”

While she worked on Jane Austen’s Bookshelf, Romney simultaneously invested years and significant capital to assemble a collection that documents the history of the romance novel in English, from its origins to the modern-day supermarket paperback. Her accompanying 500-page catalog made a case for including the genre within the scope of antiquarian books,5 and the entire collection was acquired by Indiana University’s Lilly Library, where it now supports ongoing programming around rare books and romance.

Romney’s curatorial work continues. Type Punch Matrix plans to display key titles that influenced Austen in its booth at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in April. A catalog will follow. Of course, spending nearly five years writing Jane Austen’s Bookshelf to promote a catalog seems like a lot of effort compared with the potential financial gain. Like many antiquarian booksellers, Romney enjoys researching the books that land on her desk. “It’s work that I like to do,” she said, but remembering her children and the constant need to keep money flowing into the business, she acknowledged the limits to her side projects. “I have to be careful not to be too inefficient.”

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

Corrections: After the initial publication, I changed the page-count of Type Punch Matrix’s romance catalog. The pdf is 280-odd pages, but on closer inspection, that’s counting two-page spreads as one page. The catalog itself is not paginated, but has more than 500 pages. In the last sentence of footnote 4, below, I also misstated the number of endnotes in the final book. Eight hundred is the correct number.

One might suggest simply ignoring the comments and the direct messages, but if the point is to convert social media followers into collectors, engagement is part of the process.

Quoted in Jane Austen’s Bookshelf, p. 303.

The bound galley of Jane Austen’s Bookshelf that I read last year had 800 footnotes. Romney’s publisher wanted to put them on a web site. Romney said that removing the research would be “antithetical to the themes of the book,” which provides a model for how collectors can take a deep dive into their subject matter. “If you get rid of that, you’re erasing the point of the book,” Romney said. The published version changed these to endnotes, so the exact count cannot be easily determined. Romney assures me it is still 800.

The first bookseller that I am aware of who issued catalogs of romance novels is Between the Covers, which published a series of lists beginning in the early 2000s (I think). I was able to find links to their catalog 151, from 2009 (online, pdf), which the introduction says is the first in four years. Their catalog 178 (pdf) and their ecatalog 57, from 2000 (pdf), were also devoted to the subject. Also, in 2006, when I was the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine, we did a cover story on romance book collecting.

Nice job, Mr. DTB, as always. I liked the piece on the Bauman consortium, but I was left with the same question I puzzle over when I receive their catalogues: Who can afford these books? Admittedly, my question contains at least a small measure of envy. And a larger helping of incredulity. My son was slotted to attend a state college until an Ivy League school came through with a generous scholarship. Tuition some four or five years ago was $65,000 per annum. I once asked the fortunate undergrad if he knew students whose parents could just write a check for the entire tuition. Affirmative.

I always found Rebecca to be the only reason to watch Pawn Stars. And I always relished the incongruity of a customer showing up with a signed first rather than a handful of World Series' rings. Something always bothered me about her appearances. The Pawn Boss would ask her to come calling. She'd show up and rattle off points of issue and other arcana — regardless of the book she was assessing. The setup always seemed to suggest that this was a "cold" reading. I was impressed, but I was more skeptical.

A final point: One now deceased dealer in modern firsts complained bitterly about another dead bookseller's book on collecting in that area. The charge was that its was "market building." I always wondered if the comment was actually due to the outraged bookseller not thinking of the idea first.

Wait, I lied: Another bookseller I knew (still above ground) summed up the shock and awe about ambitious prices simply: Selling rare books has always been a carriage trade.

As always

Aaron

I love every one of your posts.

I just emailed my local independent new bookstore to see if they’ll order in Romney’s book for me (if they don’t already have it).

I work in a used bookstore and bring home marvels every day (purchased with my discount) but I don’t want to wait for a used copy of this book to come through the door.