Today’s Dispatch from the Rare Book Trade is brought to you by Downtown Brown Books’s List 109, a random assortment of modern firsts recently pulled from storage, including a bunch of signed Ray Bradbury ephemera.

How to Successfully Bid on eBay Auctions

[Permalink: https://downtownbrown.substack.com/p/how-to-win-ebay-auctions ]

Did you know that a Nobel Prize-winning economist invented eBay’s auction format? I didn’t.

I discovered William Vickrey and his auctions in the academic research about eBay. But before I tell you what I found, I must make a disclaimer.

The eBay section of the official antiquarian booksellers handbook directs dealers to either bad-mouth eBay to customers or to pretend it doesn’t exist (while regularly buying there ourselves).

So as a card-carrying member of two bookselling organizations1 I’m going to pay lip service to the rules and remind everyone that eBay is a cesspool of stolen merchandise, misrepresented material, and shameless forgers. Really, it is. It probably shouldn’t be legal, and you should send your money to me instead.

With that professional disclaimer out of the way, here’s the TL;DR version of Downtown Brown Books’s Three Rules for Winning eBay Auctions:

If you enjoy bidding, do it early and often but not seriously until the end.

Sniping is the best strategy, but bidding at any time on the last day works fine.

Place your bid and then think about it for a moment. If you will regret losing by a few dollars, bid again. Repeat until the regret disappears.

If you want to know the reasons for those rules, keep reading.

The economics literature refers to eBay’s auction format, which has a “hard close”, meaning a fixed end time, as a sealed-bid, second-price auction. The winning bidder’s high bid is secret (“sealed”) and they pay one increment more than the second-highest bidder (hence “second price”). Only bids entered before the close are considered.

For example, in an eBay auction with two bidders, one of whom bids $100 and one of whom bids $1,000, the winner pays $105 and no one gets to know that they were willing to pay ten times as much.

In 1961, William Vickrey invented this kind of auction as an alternative to an English auction (the kind of auction where people put paddles up in the air). Economists often refer to sealed-bid, second-price auctions as Vickrey auctions.

But it turns out that Vickrey didn’t invent the format after all. He came up with it independently and used difficult math to prove that sealed-bid, second-price auctions produce results comparable to English auctions. (This kind of hard math won Vickrey a Nobel Prize).

Vickrey auctions really should be called Stamp Auctions because the format seems to have originated with mail-order stamp dealers in the 19th century.2 I don’t know if Pierre Omidyar came up with the format independently when he created eBay, or if he was familiar with stamp auctions, or if he had studied Vickrey’s auction model in college. In any case, eBay transformed the Vickrey format from a Nobel Prize winner’s thought experiment into the most widely known style of auction next to the traditional English auction.

Using game theory and hard math, economists proved that the best strategy for eBay is to snipe (bid at the last instant) one’s true price (the highest amount a bidder is willing to pay). In practice, however, most bidders don’t bid either their true price, nor do they snipe.

Economists have looked into the problem of people not bidding efficiently on eBay. In papers like “The net effect of advice on strategy‑proof mechanisms: An experiment for the Vickrey auction” (Masuda et al., Experimental Economics, issue 25, 2022) social scientists conclude that the mechanics of Vickrey auctions are not intuitive and that bidders get better with a bit of advice. This essay is my bit of advice.

*

Every collectible books auctioned on eBay has three sources of value3:

Public value - the approximate value that is common knowledge among collectors. Public value is the collector’s instinct that a particular first edition is “a $500 book.”

Private value - the value only a small number of people know about. For example, that a movie or TV show based on the book is in production or that the item in question is rarer than it looks at first glance.

Personal value - the value an item has only for you. Sentimental value is one kind of personal value. A book might also have personal value to a collector who needs it to complete a set and is willing to pay a bit extra for that.

Early bidding on eBay mostly signals public value.

If someone offers a book with a starting bid of $9.99 that collectors would commonly describe as “a $500 book,” you can expect it will be bid up. A bid of $200 isn’t giving away any information that potential competitors don’t already know.

The only risk with early bidding comes when the early bidding takes the item’s price above the public value. If a book commonly believed to be a $500 book is bid up to $1,000 early on, a lot of people are going to look more closely at it. Unexpectedly strong bidding might indicate that there is something especially good about the particular copy and collectors who really want the book don’t want to give that information away with strong bidding at the beginning of the auction’s run.

These cases arepretty rare in my experience, but since no one wants to alert competitors to the potential hidden (private) value of an item, I offer Downtown Brown Books’ first rule of eBay bidding:

If you enjoy bidding, do it early and often but not seriously until the end.

As long as your bidding is within the typical range, you won’t tip off competitors to your real interest. And harmlessly bidding up an item can be enjoyable. I recently sold an item on eBay that got 43 bids, 33 of which were from one bidder. Another person bid three times, and two bid twice. Everyone else was one and done. Who had the most fun?

The typical eBay bidder doesn’t like sniping because they perceive it as unfair.

Manual sniping also comes with what economists call a “monitoring cost.” This is the time you have to spend keeping track of when an auction is going to end and having your phone or computer at hand to place a bid at the last second.

Anyone who bids often on eBay, should probably invest in sniping software. I use Bidnapper, which costs $50 per year. Avoiding “monitoring costs” for $4/month seems well worth it to me. (Full disclosure: If I could have figured out how to do an affiliate link here, I would have. However, the coding eluded me so this is actual, uncompensated information).

But you don’t actually have to snipe at the last minute. The majority of auctions end with no last minute bids. One study from years ago estimated that only 30% of auctions got last-minute bids. I recently looked at the eBay’s sold-at-auction books and in the 20 most hotly contested book auctions only nine (45%) were won by snipers; in other words, most of the items were won by people who didn’t wait until the last minute to bid.

Bidding seriously on the last day (whether one has already bid early and often but un-seriously or not) is almost as good as bidding at the last minute, and it has a much lower monitoring cost.

Placing a serious bid on the last day leaves open a window of time for competing customers to bid. Competitors may learn something about your private and personal value of an item from those bids and it may encourage them to bid again if their first bid didn’t put them in the lead. That is definitely a risk, but the time window for that to happen on the last day is relatively short, and the risk is correspondingly small.

Snipers using automated software can’t learn from bids placed on the last day. By the time they know their software has bid, the auction is over. Only people willing to incur monitoring costs in order to manually snipe will be able to react if an earlier bid is higher than their first snipe.

Going back to my original example, let’s say an item is sitting at $100 on the last day. At a convenient time, you put in your final bid of $1,000. You have the current high bid on eBay at $105. No one knows your limit. If a manual sniper jumps in with 10 seconds to go and bids $250; you remain the high bidder at $255. The sniper might try another bid, probably just a bit higher, say at $300, but you still win.

In this scenario, bidding early might have cost you $50 (the amount of the live sniper’s second bid increase, from $250 to $300). But maybe not. If you had also manually sniped, the final bidding may well have been the same.

This explains my second rule:

Sniping is the best strategy, but bidding at any time on the last day works fine.

*

In an email to me, a customer recently lamented their lack of success on eBay: “The truth is I seldom win auctions,” he wrote. “The bids I place early are typically trumped by $1 at the last minute.”

This appears to be a complaint about sniping, but I think it actually reflects the fact that the bidder would have bid again, if given the chance. In other words, their early bid wasn’t the full price they were willing to pay.

Economic and psychological experiments have shown repeatedly that consumers hate hate hate to overpay. Most eBayers don’t bid their true price because it feels like overpaying, and they want the psychic benefit of getting something for $50 when they were willing to pay $100. Before we pay $100 for something, we prefer the assurance that someone else is willing to pay at least $95.

It’s exactly these sorts of problems that Vickrey thought he had solved when he came up with his sealed-bid, second-price auction format.

Yet perhaps with the exception of stamp collectors, who have a 125-year tradition of buying this way, most collectors find placing their highest possible bid on eBay to be counterintuitive.

Part of this hang up may come from our familiarity with sealed-bid auctions. Sealed-bid auctions are how offers are made on real estate in most parts of the country. Buyers pay the price they bid regardless of how much the next highest buyer offered.

Strategically, sealed bids are complicated.4 The last thing anyone wants to do is to offer $500,000 for a house only to learn that the next highest bid was just $400,000. That buyer is going to be very, very unhappy.

Objectively, that unhappiness doesn’t make any sense. The buyer got the house they wanted at the price they were willing to pay. If instead of $400,000, the next highest bidder had offered $495,000, most buyers would be thrilled to pay $500,000. Winning always feels better when it is snatched from the jaws of a near defeat (or from the hands of a grasping competitor). In both cases, however, the money and the house are the same; they way the deal feels is the only difference.

I suspect that aliens visiting the earth might well find this aspect of human behavior impossible to understand, and it probably is, but that’s why we invented the profession of real estate agent—to prevent this sort of psychic calamity by making sure their clients’ bids aren’t wildly out of line.

eBay auctions are not straight sealed-bid auctions, but many, if not most, buyers bid as if they were. Unsuccessful bids are often placed based on what the potential buyer would like to pay, not what they are willing to pay. They anticipate scoring a good deal and fail to anticipate their disappointment when they are outbid. This leads to collector regret, which we all know is sometimes a lifelong affliction. I still regret losing what would have been the best item in my personal collection by underbidding on eBay more than twenty years ago. Most every time I look at my collection I think about what’s not there as much as what is.

In an English auction, the competition against other bidders gives bidders confidence in their bids. One frequent auction buyer I know likes to say, “Trust the underbidder.” On eBay, where there is very limited time to place new bids at the last instant, bidders need to invent the underbidder. The competition becomes a thought experiment.

A perfectly actualized eBay bidder would think about how much they are willing to pay, and they would bid that amount at some convenient time before the auction ends.

Most of us, in practice, are not perfectly actualized, and so many successful eBay bidders solve this problem by bidding more than once.

If you look closely at eBay auction results, you will see a regular pattern of the high bidder bidding again while they are still the high bidder.

I think the act of placing a bid makes it simpler to imagine an underbidder. After someone places a bid of $100 and is the high bidder, it is easier to ask the question, “Will I be unhappy if I lose this auction to a bid of $105?” If the answer is yes, the high bidder can bid again. The price on eBay doesn’t change—the high bid showing on the site is still just one notch above the highest previous bid.

This observation leads me to my final rule:

Place your bid and then think about it for a moment. If you will regret losing by a few dollars, bid again. Repeat until the regret disappears.

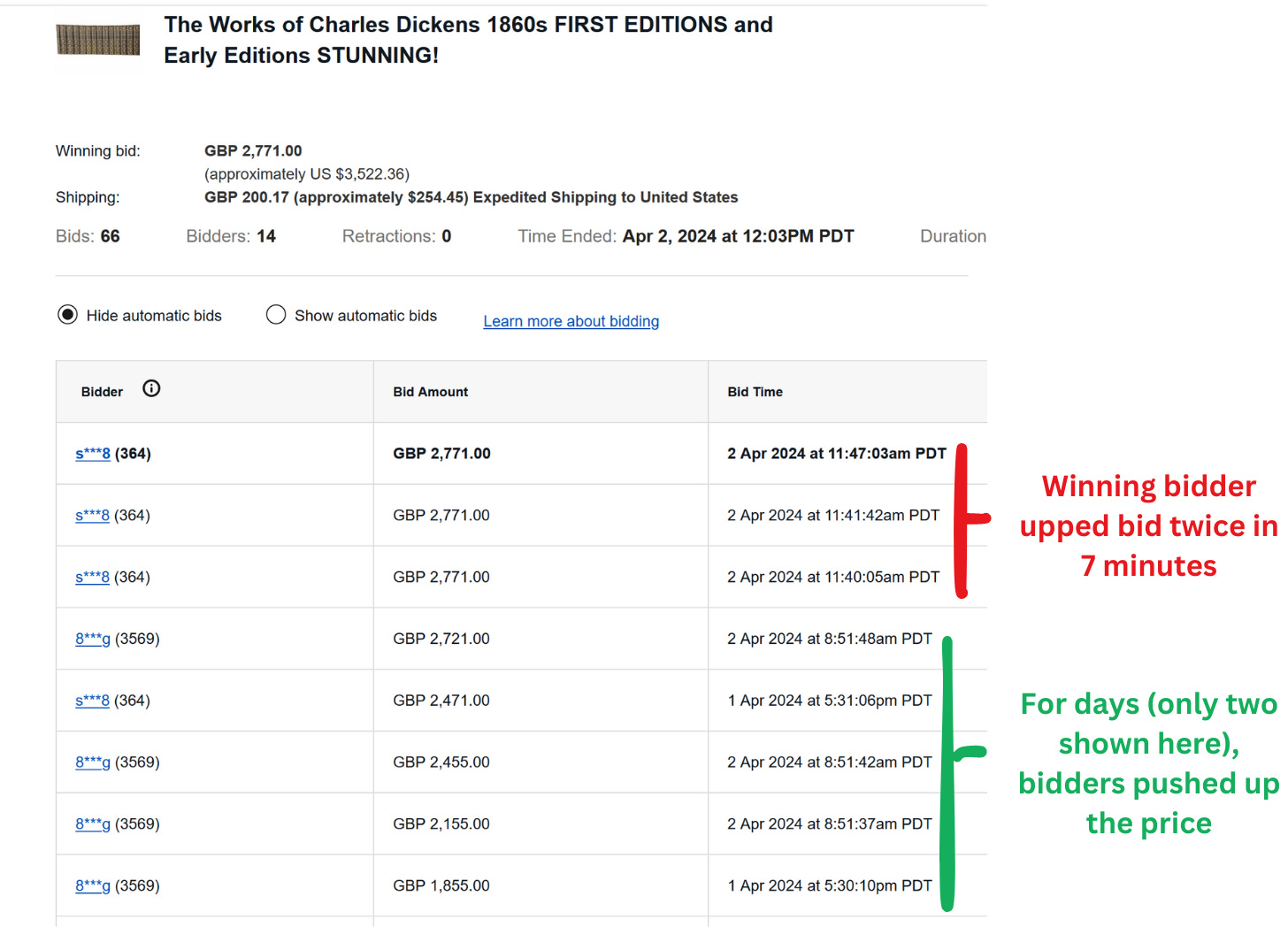

One of the most active of recent eBay book auctions shows my rules in action. This lovely set of Dickens received 66 bids from 14 bidders and sold for roughly $3500.

Lots of bidders, including the winner, placed bids early in the auction (rule 1). The top two bidders placed their bids on the last day, one three hours before the auction ended and one 20 minutes before. No one sniped at the last minute (rule 2). The winner bid and then bid again and then bid a third time, all while having the high bid already (rule 3).

Those extra bids never went into effect because the first of the bids won the auction, but they ensured the bidder wouldn’t regret losing if someone had been willing to pay more.

I wonder how the underbidder felt? That eBayer bid over and over again with slight increases between bids. Three hours before the auction ended, the underbidder placed a bid that was exactly one increment above the previous high bid. Then they stopped, unlike the winner, who took the lead and then doubled down and won.

If you have other insights into eBay auction bidding, please leave a comment.

For those of you in the US, I wish you a happy Memorial Day (for those readers in other countries, shouldn’t you get back to work?),

Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

IOBA issued a lapel pin to all its members. I can’t show it to you—it’s our secret sign so that members can recognize each other in public settings.

If you are interested, you can download a pdf of a paper by David Lucking-Reiley on the history of second-price auctions before Vickrey.

These three kinds of value are loosely adapted from the economic literature with my own terminology in an attempt to make the explanation easier to understand.

Sealed-price auctions require the kind of “I know that you know that I know that you know…” logic loop that was so brilliantly satirized in the Battle of Wits scene in the film The Princess Bride.

I have to disagree with the bid early and often strategy. By bidding early, you are tipping off other bidders that there is competition. The only time to bid is in the last few seconds. It is at that moment you can decide the max you’re willing to pay and take other bidders by surprise. Bidding early and often only serves to drive up the price. You might lose. You might win. But it’s on your terms.

Love you dearly but promoting eBay tirelessly is tedious. Also your ABAA membership card is out of date.. just sayin'... You were recently quoted as justification for a collector buying on eBay knowing the item was probably stolen! I tell my customers who brag about their eBay finds, "good luck reselling when the dealer or auction house requires proof of purchase a.k.a. provenance"...