Frankensigned Monsters a.k.a. Signed on a Tipped-in Page

Plus a newly cataloged Suntup Press collection

This free newsletter is brought to you by Downtown Brown Books’s List 115: Suntup Press. I am very pleased to offer titles from the collection of Michael Russem, a book designer who worked on many of the key Suntup Press titles. The numbered issues in his collection are all PC copies, signed by Russem as the book designer. (A few are still available as of March 2025).

Frankensigned Monsters

or, An Inquiry into the Nature of Certain Books with Tipped-in Signatures

If you collect modern books, you’ve surely come across one described as “signed on a tipped in page” like this “signed” first edition of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian that recently sold on eBay for $5,000. Or this $4,500 copy of John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces “signed by author Walker Percy, who wrote the foreword for the book, on a tipped-in page1 professionally affixed by a bookbinder.”

Tip in is a term of art in bookbinding. John Carter defined it as “lightly attached, by gum or paste, usually at the inner edge.”2 The difference between tipping in and gluing on or mounting is that tipped-in sheets are affixed on just one edge.

I’m not sure about the origin of the term. The Oxford English Dictionary dates it to the 1940s, but it appeared in James Maitland’s American Slang Dictionary fifty years earlier as the verb bookbinders used to describe inserting corrected pages (called cancels) into a book.3

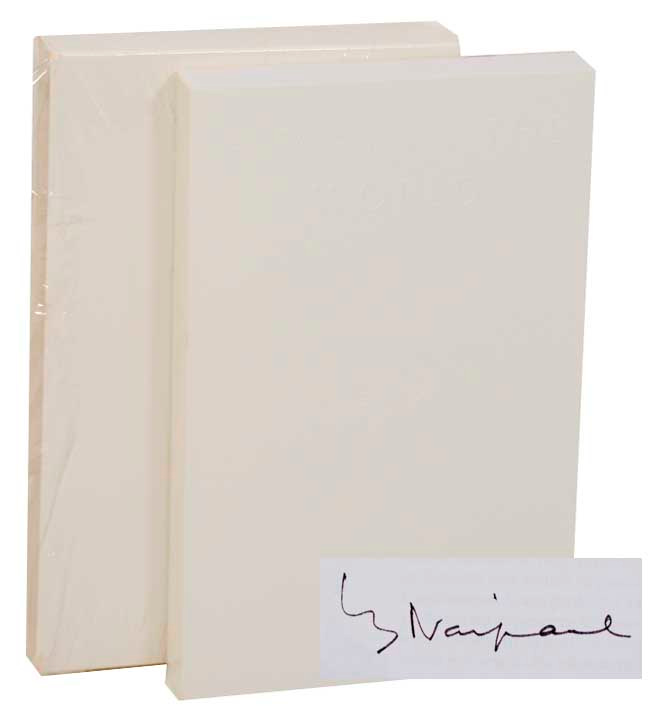

The first book I can remember encountering with an added signature page was the advance reading copy (ARC) of V. S. Naipaul’s A Way in the World in 1994. I was collecting Naipaul back then and in the pre-Internet era, I was thrilled to find a signed copy (in a paper slipcase, no less) because Naipaul didn’t sign books that often.

Naipaul wasn’t the only author who received the deluxe treatment. The literary publisher Alfred A. Knopf put out quite a few of these signed ARCs in slipcases in the 1990s to promote their major titles.4 There are copies of John Updike’s Rabbit at Rest (1990), Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses (1992), and Joan Didion’s The Last Thing He Wanted (1996) issued in this format.

The reason these books are signed on tipped-in sheets and not the book itself is practical. For a publisher to produce a signed book, there are basically four options, listed here in reverse order of practicality:

Ship books to the writer to be signed and returned. Books are heavy and no author wants to risk hurting their back moving, unpacking, and re-packing 30-pound boxes of books. That’s what booksellers are for.

Ship copies of one gathering of the book to the writer to be signed and returned. Books are printed in units of pages called gatherings, usually 16 pages long (but sometimes 8 or 32). Sending part of the book is less expensive than shipping finished copies, but the boxes of paper can still be quite heavy. If the gatherings get bent or warped, they may jam the binding machine.

Fly the author to the books. This is moderately expensive, what with author requests for comfortable plane seats, the price of a decent hotel, mini-bar charges, transportation to and from the facility, and what not. And most authors would rather be home writing than spending a couple of days traveling to sign books.5

Send loose sheets of paper for the author to sign and return.

The last option is the way it’s usually done.

Since the beginning of this century, the efficacy of book tours and author events have declined, and increasingly publishers have been offering books with tipped-in signature pages in lieu of the writer visiting a store in person. Most of these books have “signed” stickers on their dust jackets and they are available, like copies signed at events, at the cover price.6

The earliest book I have sold that was signed on a tipped-in leaf was a copy of the poet Robinson Jeffers’s The Double Axe, from 1948. The earliest example I could find in my references (in about an hour’s searching) is Robert Frost’s Collected Poems from 1939, some copies of which were signed on a tipped-in sheet.

Whether these early examples of tipped-in signatures were sent to bookstores like they would be today or whether they served some other purpose is often unclear today.

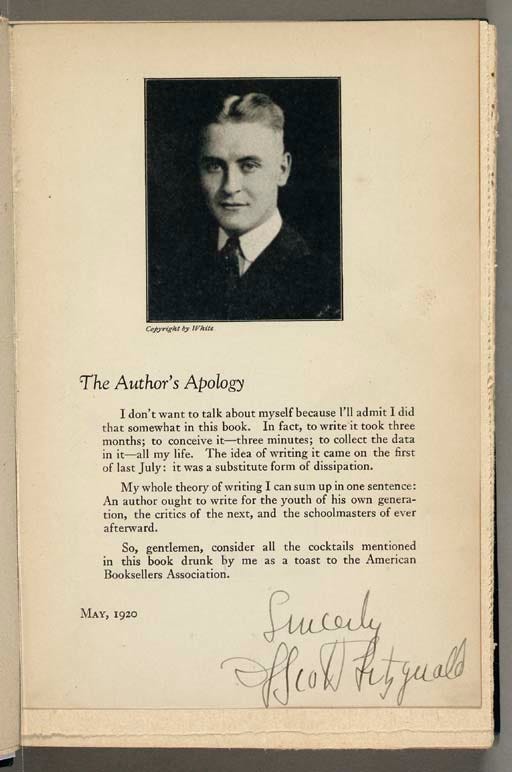

In 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald signed 500 printed sheets that were inserted into copies of the third printing of This Side of Paradise that his publisher distributed to members of the American Booksellers Association.

The “apology” isn’t one, and I don’t know what Fitzgerald was pretending to apologize for. At the time, printed note may well have come off as arrogant, only it proved to be true in his case. “My whole theory of writing I can sum up in one sentence: An author ought to write for the youth of his own generation, the critics of the next, and the schoolmasters of ever afterward.”

The number of copies of a book that a publisher puts out with an autographed page varies and isn’t usually made public. On the low end, maybe 200 copies get signed this way. Five hundred to one thousand seems more likely for modern books. To commemorate his fifty years as a writer, Norman Mailer signed sheets inserted into every copy of the first printing of The Time of Our Time, 25,000 in all. That may be the record.

First Edition Circle

Much of the credit for the practice of distributing books signed on tipped-in leaves probably goes to Kroch’s and Brentano’s Bookstore in Chicago. Between 1954, when the bookstore chain opened, until 1995, when it closed, K&B put out four or five hundred signed titles through its First Edition Circle. These books came with a printed card or bookmark and a letter from the store; bookmarks turn up now and then; the letters are scarce. Booksellers and bibliographers often describe First Edition Circle copies as “signed on a tipped in page” without further elaboration.7

The First Edition Circle worked much like the Book of the Month Club, only with signed first editions.8 Twelve times per year, subscribers received a book in the mail, which they could review and then either buy or return.

Sometimes, K&B arranged to have authors visit their offices to sign books. More often they commissioned copies from the publishers. Publishers were undoubtedly keen to custom manufacture signed books for K&B because they guaranteed a large sale as well as excellent promotion in Chicago and wherever First Edition Circle members lived. According to Robertson Davies’s bibliographer, K&B ordered 1,000 signed copies of What’s Bred in the Bone for the club, a substantial percentage of the 26,750 copies of the first American printing.9

It seems that many if not most of the First Edition Circle subscribers were readers more than collectors. Even though the club distributed as many as several hundred thousand signed books, they are not especially common on the collecting market. In fact, as I write this, not one of the 1,000 K&B copies of What’s Bred in the Bone are listed for sale on the Internet. The emphasis on readers is borne out by a member of the First Edition Circle quoted in the Chicago Tribune, “She said she’d been a member for as long as she could remember because ‘it was responsible for turning [her] on to authors [she]’ d never read before.’”

I think a strong case can be made under the standard principle of bibliography that whenever a publisher makes a change to a book (particularly a first edition) it counts as a separate variant. In this case, K&B First Edition Circle titles are “signed issues” and not simply signed first editions. For the club titles, there are First Edition Circle copies and regular trade copies. Despite the surprisingly low survival rates of most titles and the fact that the books are signed, collectors have not shown any special interest in them.

Frankensigned

Publisher-issued books signed on tipped-in sheets are very different from the after-market frankensigned books proliferating today. Whether the signed pages are added by booksellers, collectors, or “professionally affixed by a bookbinder,” these pasted-together books are like Frankenstein’s monster, an assemblage of parts cannibalized from other works. When I see one, I want to channel Mary Shelley and ask, “Accursed creator! Why did you form a monster so hideous …?”

In order to make these books a signed page has to be cut out of another book and pasted into a more valuable first edition, ruining one book and spoiling the other. This is happening with some frequency with Cormac McCarthy’s books. The 2022 signed box set of The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy’s last two novels, comes with two signed, tipped-in leaves (one in each book) for the price of one. Those leaves are tempting targets for removal and now appear in other McCarthy books [here, here, here, here].

The increasing acceptance by collectors of frankensigned books is a boon to forgers. One of the great drawbacks of faking signatures in books is that the forger only gets one shot at it. If they screw it up, they have to get another book and start over. But if a forger can sit down with a stack of blank sheets and sign over and over until they get it right, the forgeries can be hard to detect. It’s so much easier and much less risky to tip in a forged signature sheet than to fake-sign an actual book.

As a collector, I understand the desire for signed copies of books that are too expensive to buy or nearly impossible to find. But buying a frankensigned copy with a page added from another book requires a lot of wishful thinking to pretend that it is really signed.

I suggest this:

Buy an unsigned copy of the book you want signed and a signed copy of a potential donor book. At any time, you can cut out the signed leaf and paste it into the other book. Knowing you could do it is almost the same as actually doing it. If you truly love books, I suspect you’ll find it hard to take a box cutter to the donor book. Don’t let someone else do that dirty work for you.

Much like restored dust jackets, which swept the bookselling market a couple of decades ago, I suspect that frankensigning books will prove to be a passing fad and that frankensigned books will be hard to sell in the future. Right now, aftermarket tipped-in signatures might seem like a way to get a signed first edition on the cheap, but when collectors go to sell them, they may well find that all they bought was a good book ruined.10

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

Most people will say that a book is signed on a tipped-in page. I use that phrase, too, but probably tipped-in leaf is more accurate. The leaf (a single sheet of paper) is tipped in; the author signs a page (one side of the leaf). Just in case someone from the book grammar police subscribes to this newsletter, I’m going with tipped-in leaf. In case anyone from the regular grammar police is reading, I’ll also add the hyphen (tipped-in leaf), which I think is correct, even if booksellers, including me, rarely write it that way in the wild.

The definition of tipped in comes from ABC for Book Collectors, 8th edition (2006), as revised by Nicolas Barker. This essential dictionary for bibliophiles can be downloaded for free from the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (of which I am a member, so you’re welcome).

I tend to think of the OED as near infallible, but it defines “tip in” as the same as “paste-in”, but “tip in” is by far the more common term. Maitland defined it in 1891 as “in bookbinding, to insert new pages in a printed book in place of defective pages.” Although it rarely happens in the modern era, in Maitland’s era it was routine for printers to print single corrected leaves, cut out an error-filled leaf, and tip in the newly printed one in its place. The new leaf is called a cancel (the one removed is called a canceland or cancelandum, but don’t try to use those words in Scrabble).

Pantheon, another Random House subsidiary, produced signed ARCs in slipcases. Few or no other publishers tried it, and Random House stopped in the late 1990s.

In truth, authors these days are more likely to incur expenses related to gym use than draining the mini bar. When they travel, big-name writers often get “author escorts” who specialize in driving writers from place to place.

Over the summer, I stopped in at Eagle Harbor Books, on Bainbridge Island, located across Puget Sound from Seattle. They had lots of first editions signed on tipped-in leaves, including stacks of James by Percival Everett, which I stupidly didn’t buy.

As one example, the Author Price Guide series by Pat and Allen Ahearn list many First Edition Circle books as “signed on a tipped in page” without indicating who commissioned the insertion.

The K&B First Edition Circle seems to have been a logical extension of a signed books program that Adolf Kroch developed years earlier. Kroch’s Bookstore commissioned signed bookplates at least as early as the 1930s.

A Bibliography of Robertson Davies by Carl Spadoni, A68a.1.

In the interest of space, I have neglected the 19th century fad for extra-illustrated books and its echoes in the early 20th century, when many collectors pasted letters by authors onto the pastedowns of books. Both of these practices were better than the usual approach of autograph hounds who cut signatures off of letters and either glued them into books or onto index cards for easy filing.

A reader pointed this out to me: John Quincy Adams bound copies of his speeches in red morocco and then had a presentation leaf tipped in. In 1835. Ahead of his time!

https://www.williamreesecompany.com/oration-on-the-life-and-character-of-gilbert-motier-de-lafayette-delivered-at-the-request-of-both-houses-of-the-congress-of-the-united-states-before-them-in-the-house-of-representatives-at-58519.html