Collecting for Investment or, What Does Venture Capital Have to Do with Books

Lately I’ve been rethinking my ideas on collecting books for investment, especially my recommendation about pursuing highspots.

In an earlier Dispatch, collecting highspots was offered as my rule #3. Upon further consideration, the first three rules for investing in books should probably be

Highspots, Highspots, Highspots.1

Highspots are, in case the term is unfamiliar, the most sought-after, exceptional, and iconic books in any field. Examples would include Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, or the first edition (1611) of the King James Bible.

Those books are out of the price range of most collectors, but the definition of highspots encompasses more than just household-name books.

Every collecting niche has its own highspots, which may not be widely known beyond a small pool of collectors. And they may not be all that expensive.

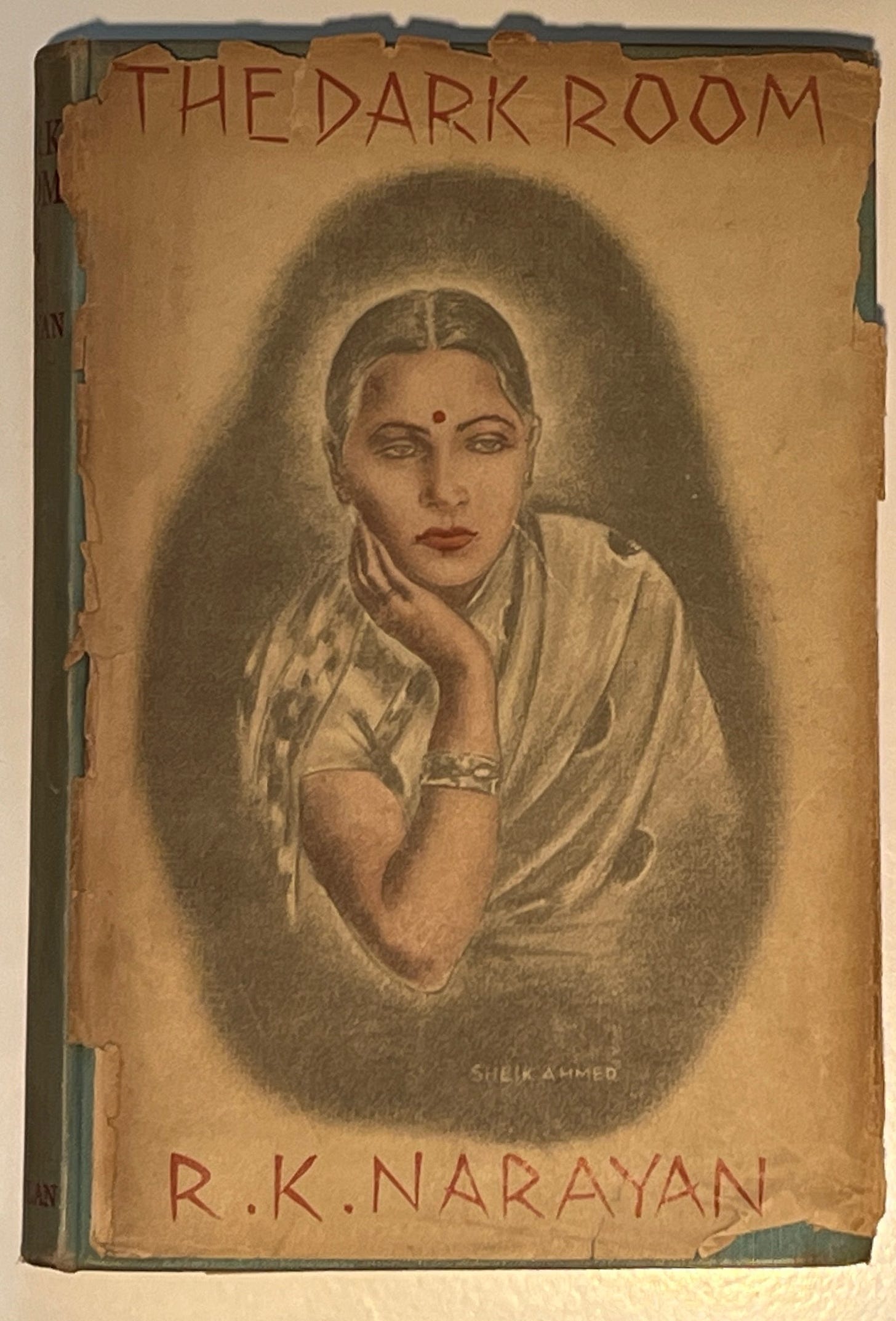

For example, I collect the first editions of R. K. Narayan, the first professional novelist in India.2 His third book, The Dark Room (London, 1938), is very scarce. A copy turns up every ten years or so. In three decades of collecting, I’ve managed to acquire a first edition with three-quarters of a dust jacket. I’d really like a copy with a complete jacket.

Narayan is not widely collected but I do have some competition. I wouldn’t be surprised if a copy of The Dark Room in a jacket exceeded a thousand dollars at auction (since it’s obscure, a copy could just as likely pop up on AbeBooks for $100, which is how I came by the copy I have).

A thousand bucks isn’t nothing, but for a highspot it would be a reasonable purchase for most any collector, even if it were a bit of a stretch financially. Regardless of your pocketbook, the principle is the same. There’s the price you’ll pay for a book any day of the week and a price that will give you pause to think.

Compare The Dark Room with a more widely recognizable highspot from 1938, Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier, which is at least ten times more common, and yet it is also ten times more expensive. That’s what happens when the demand far exceeds the supply and how highspot pricing can vary from niche to niche.3

My revised thinking about collecting for investment was brought on by Nate Silver’s4 new book, On the Edge, which is a look at how people who analyze probability and risk-taking are changing the economy and society.

One of Silver’s subjects is venture capital firms and how they choose their investments. Basically, VCs are looking for assholes (to put it bluntly) who have ideas that could transform entire industries. Silver quotes one VC who wants the founders of the companies he invests in to have “a sense of anger that is not leading them to despondence, but to motivated revenge.” That certainly explains the bro culture of Silicon Valley and its move fast and break things ethos.

I’m more interested in the second part of the formula for VC success. VCs are not looking for good, profitable companies, which they derisively term “lifestyle businesses.” Instead, they want the business equivalent of highspots that will return 10x or 20x or even 100x on their investment.

Of course, a lot of VC-backed companies never take off, which makes investing in the tech sector seem risky. One of Silver’s insights is that if an investor has sufficient capital (either their own wealth or through an investment fund), they will be able to place enough bets that making a lot of money becomes a statistical near certainty. It’s like they are trying to win a multi-billion-dollar PowerBall lottery, and they have enough money to buy all 300 million tickets.

A similar idea applies—albeit at a much smaller scale—to book collecting and to nearly every book collection.

For many years, I have been aware that whenever I purchase a collection, a few books end up accounting for most of my sales. If I buy 10 books, the top three make the majority of the money. If I acquire a collection of 1000 books, the top 50 will generate nearly half of my sales.

Most book dealers know this intuitively, even if they’ve never looked at their sales systematically. Antiquarian booksellers talk about “getting out” of deals after selling a few books (recouping their initial investment) or in a few months after a deal is done. The rest is “gravy.”

(Gravy is a bad analogy. What is often called gravy is really the meal itself. Once a bookseller’s investment has been paid back, the gravy, or gross profits in accounting terms, go to paying the bookseller, rent, and every other expense. Only when all of that is taken care of is there any gravy.5 )

While booksellers tend to view collections through the prism of their best books, in my experience collectors rarely do. Collectors tend to focus on the bulk of their library, feeling an attachment to nearly every volume. This is the heart of collecting, and I think it should be this way. But that emotional attachment to books has little to do with collecting with an eye for investment, if that’s what a collector wants to do.

The market value of any collection comes down to a small number of key books, not from adding up hundreds or thousands of modest sales of more common or less-sought-after titles. Venture capitalists, who gain a professional advantage from not caring too much about the companies that fail or “just” become regular profitable businesses, make their returns the same way. They look at their big winners and don’t care much about the rest.

This trend is clearly visible in the economics of single-owner sales, or auctions devoted to the books belonging to one person (while not the perfect data set, there isn’t a better one where the numbers are both public and reliable).

Just for kicks, I went through 90 days of RareBookHub’s Recent Reported Auction Results, a new tool for browsing entire auctions and not just individual lot results (subscription to RBH required).6

I looked at auctions from June to August 2024, and I found seven single-owner sales to examine. I didn’t cherry-pick to produce favorable results, but I also didn’t consider every possible auction. I’ll leave the specific details in a footnote.7

Generally speaking, half of the total sales from single-owner auctions often come from the best 5% to 10% of the items sold—the highspots of each collection.

The single-owner sale that got the most attention during my research window was the William A. Strutz collection at Heritage (June 27, 2024). Strutz assembled the sort of library that any literate person would recognize. It was mostly household-name first editions, like Frankenstein in the original boards and inscribed copies of The Great Gatsby and The Hobbit. The 226 lots put under the hammer made an impressive $5.7 million. Yet the top 17 items (7.5% of the lots) contributed more than 50% of the auction total. Seventeen books for nearly $3 million.

The Strutz sale might be a bit misleading because it was just the first of several sales planned from his library.

So I looked at Ricky Jay’s sale at Potter and Potter on August 17. Jay (who died in 2018) was a great magician, a beloved character actor, and a major collector of books and ephemera related to magic and sideshow acts. Magic is not a widely collected subject,8 but those who do collect in the field are very committed. The P&P sale did just over $400,000.

However, in order to show that the idea of highspots works even in specialized fields like magic, I looked at all four sales from the Jay estate, beginning with Sotheby’s in 2021 and continuing at Potter and Potter in 2023 and 2024.

Jay’s collection, in 1892 lots, sold for $6.1 million (do you believe in magic now?). The top 6.5% of the items (123 lots) accounted for 46.5% of the total, a concentration of highspots similar to the smaller-scale, greatest-hits-focused Strutz sale.9

The top-10% principle also basically held for Mike Glad’s massive collection of animation (Heritage, August 16–19), which grossed $4 million over nearly 1600 lots. Half of that total came from 189 pieces (11.8% of the total).

Even library collections seem to work this way. Grant Zahajko sold off books from the defunct Birmingham-Southern College (July 31–August 1, 2024). The 984 sold lots were all ex-library books. The sale achieved $475,000. Half of that came from just 34 items (3.4% of the total).

You don’t need massive collections for the principle to work. On July 2, Sotheby’s put a number of early manuscripts on the block. The Ernst Boehlen library sold just 47 lots, mostly at least 500 years old, for £790,560 ($1 million). More than half came from the four best items.

Another million-dollar library sold this summer also makes my case, the Arthur Lyons collection of science and medicine books (Bonhams, June 25 and 28) sold 246 lots. Half of the value came from the top 13 (5.3%).

The Ricky Jay collection was substantial, but I wanted an even bigger example. At random, because he came up in conversation recently, I picked the William Reese collection. Bill was a giant among booksellers and a prodigious collector.

Christie’s sold his library of rare Americana and Herman Melville first editions over four sales in 2022 for more than $19 million. The top 30 lots (5.2% of the total) accounted for half the results.

A colleague of mine warned that looking at single-owner sales could be misleading because they generate a lot of attention and probably get more bidders than the typical book auction.

Fortunately, there was a smaller single-owner sale in my summer auction sample.

Purcell Auctioneers offered the books of the Irish historian Frank Meehan (1926–2012) on July 17. Half of the $74,000 total came from the top 90 lots (15.6%) out of 577 sold. A quarter of the total came from 23 items. The Meehan books are a bit of an outlier, but they were also more of a private academic library than a first-edition book collection.

The results of this informal look at single-owner sales offers, I think, several lessons for collectors, particularly those who are concerned with how much their collection will bring when it sells.

First, as the small Meehan sale suggests, accumulating is probably less effective than collecting when it comes to building value.

Second, there are highspots in every field and niche of books. It is possible to have a multi-million-dollar collection of magic or animation art, two areas that the majority of dealers and collectors rarely think about. And it was possible for Ricky Jay to have just over 100 magic-related items worth $3 million. Something similar will be true of most collecting niches.

Third, you need to acquire really good material in your field. When collecting, keep in mind that your best chance to see a solid return on your collection is not for all of your books to go up in value but for a group of them to go way up in value. Spend at least some portion of your collecting budget with that in mind.

Someone long ago—I have forgotten who—gave me really good collecting advice, which I ignored.

“Buy the most expensive books first,” he said. Inexpensive books (i.e., common books) are likely to remain common, at least for the foreseeable future. Rare books only get rarer. Copies are lost or damaged or they go to libraries. The number in private circulation tends to decline over time. Saving all your collecting money for an entire year to buy one really good book is probably a better investment strategy than waiting 20 years until you have more money to buy key highspots that have become even more expensive.

The problem with this advice is that it’s not much fun.

When you start collecting, everything is new and exciting. Most people with even a $100 per month budget would rather buy a bunch of less expensive items than one $1200 piece at the end of the year.10

Collecting with investment in mind always runs up against the fact that optimizing for return often isn’t as enjoyable as collecting items because you like and want them.

Another hard lesson about collecting is that the people you will have to sell your books to are likely going to be from a different generation with different interests than you. If you are planning to sell your books in, say, 30 years, your target market is now in their twenties. They’re kids! Who knows what they are doing on TikTok and SnapChat, but whatever it is may well shape their collecting in the future.

The key may be to think more like a venture capitalist. Venture capitalists don’t know which company is going to be the next big thing, they only know that if they place enough bets some of them are likely to really pay off.

VCs don’t just write checks to anyone who asks, however. They carefully vet companies and try to pick the most promising ones. In book collecting terms, they don’t buy just any copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, they look for the best one they can afford. And they might add Donna Tartt’s The Secret History or Percival Everett’s Erasure to hedge their bets about authors from the 1990s who will be popular in the future.11

There’s one final rule about pursuing highspots. It’s a good idea to mentally prepare yourself to step up when a key highspot finally comes along. I’ve been waiting more than 15 years to upgrade my copy of R. K. Narayan’s The Dark Room. I hope I’ll be able to channel my ruthless inner VC when I finally get the opportunity.

*****

Further Watching

I wouldn’t be surprised if these Instagram videos turn out to be Chinese government propaganda, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t beautiful to look at and fascinating to watch.

Here is a short documentary on traditional bamboo papermaking. For an Instagram video, it goes on for a while, but the process has a staggering number of steps. In the video, I was impressed by @xie_xiaohuaa’s martial arts-like technique for getting out of the fermentation pit:

I’ve seen papermaking before (and have even made a few primitive sheets myself). I was not expecting her next video to be about making movable type from scratch.

John Carter and Nicolas Barker’s entry for high-spot in their ABC for Book Collectors reads:

‘High-spot’ collecting is a sort of dictated eclecticism. Somebody or other has listed or selected one particular book by an author as his best, or the commentator’s favourite, or simply the one thought to be the most esteemed by collectors. And in due course people who collect on the table d’hôte rather than the à la carte system concentrate on this particular work to the exclusion of all the others, thus condemning themselves to blinkers and frustration and their booksellers to despair. Less prevalent than of yore, if only because the books are harder to come by, but still the resort of collectors with more money than sense.

I don’t think it’s less prevalent anymore.

Other Indian authors published novels before Narayan, but they were expats, living mostly in England.

A more extreme and perhaps more apt example of a valuable book from 1938 would have been Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, with a current asking price of $78,000. Greene was R. K. Narayan’s champion with British publishers; he found homes for Narayan’s first three novels—each with a different publisher—because the books sold so poorly. However, Brighton Rock is a niche item—most people today, even active readers, won’t recognize the title. Rebecca remains familiar because of the Alfred Hitchcock film based on it.

Nate Silver is the election forecaster who gained prominence at The New York Times and then the website 538. He has returned to his roots as an independent blogger/writer, now on Substack.

Or perhaps the analogy is a good one. Maybe a lot of booksellers do think that getting their money back is the main goal and that the rest is gravy. That could explain why so many book businesses are anemic—just eating gravy isn’t a healthy diet.

On RareBookHub, you can find the results of an individual sales in three ways:

In the search results, at the far right of each line item you’ll see an “A” icon. Clicking this will take you to a summary page where you can select “View All Auction Lots.”

In an item detail page, you can click the hyperlinked “Auction Name.”

You can change the drop down menu to the left of the search bar to “Auction Report” to search for a sale by name.

The seven most recent sales were selected from the list of completed auctions from June to August 2024. I did not consider single-owner estate sales with some books or single-owner collections with additional material from other sources. I excluded sales with sell-through rates of less than 80%. I also mostly excluded sales that were just one part of a larger collection.

Here are a few results from sales that I ultimately excluded:

June 27. John Collins Library at Forum. Half the value came from the top 18% of lots, but the 321 lots here were a small fraction of the library—the books with provenance and those in signed bindings were sold off previously.

Kimball Brooker was a great collector who I had the opportunity to meet a few times. One of his sales happened inside my research window, but it was just one of eight planned sales. The first three at Sotheby’s (London and New York) had 488 lots sold totallying $12.3 million. Half the value was in the top 20 items (4%)

There doesn’t seem to be even one member of the ABAA who specializes in sleight-of-hand magic (two list “magic and experimental science”, but they are referring to magick and alchemy).

This is a free newsletter and working out how many lots would bring Ricky Jay’s total to 50% would have required analyzing an additional 1200 items so I didn’t do it. My back-of-the-envelope estimate is that roughly the top 8% of items supplied 50% of the value.

The strategy of buying fewer, more expensive books does carry risk. You won’t be buying as many tickets in the book-appreciation lottery, which means you might lose all your bets. However, the odds that a moderately expensive book today will be a very expensive book in a couple of decades (the minimum time horizon for any collection aimed at investment) is much greater than the odds that a cheap book today will be very expensive in the future.

Yes, I know that technically Everett’s Erasure came out in 2001, not the 1990s, but both Everett and Wallace started publishing about the same time.

Good piece and worth expanding into a full-scale article for (say) The Book Collector with the editor of which I work closely. It probably wasn'ty me but in talks on book collecting for decades now I have started with the advice: "Buy the most expensive book in your area of interest first as it is the one most likely to get away from you later on and it will be the easiest to resell if you want to walk away"...