Backlist: A Bibliography of Larry McMurtry's In a Narrow Grave

How to identify the first edition, “skycrapers” issue, and a true account of the book's publication history without the usual Texas-sized exaggerations.

This essay was originally published on Downtownbrown.com in 2021. I would like to extend my thanks to the booksellers Jim Bowling, Burnside Rare Books, Cahill Rare Books, Herland Books, and Ed Smith for sharing information about their copies of In a Narrow Grave, and to the Wittliff Collection at the Southwestern Writers Collection, Alkek Library, Texas State University, San Marcos.

In a Narrow Grave

The printing history and legend behind the first edition of Larry McMurtry’s In a Narrow Grave, one of the great 20th century Texas books, has been the subject of myth and misinformation for years. This is an effort to set the record straight and identify the various printings and issues for this most collectible book.

Scroll to the end for the Bibliography

*

It’s fitting that a book about Texas has generated a Texas-sized collection of tall tales, half-truths, flights of fancy, and out-and-out fabrication.

That book is Larry McMurtry’s first collection of essays, In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas [Austin: Encino Press, November 1968], written when McMurtry was known as much for the movies that had been made from his books as for the novels themselves. The front panel of the dust jacket of In a Narrow Grave identifies McMurtry as the author of Hud, which was the name of the Paul Newman movie based on McMurtry’s novel, Horseman, Pass By.

Improbably, these essays which reconsidered Texas’s literary past and defined the state’s culture for the future, became his first stand-out work. A fiftieth anniversary edition was published in 2018 and the book has been continuously in print since its first publication.

After the manuscript was rejected by McMurtry’s New York publisher1, In a Narrow Grave was issued by a regional outfit, Bill Wittliff’s Encino Press, which released several hardcover printings and a signed, limited edition.

Among book collectors, these essays have become legendary. The collectibility of In a Narrow Grave is driven by the scarcity of first printings on the market, and it is undoubtedly enhanced by a comical typo: “skycrapers” for “skyscrapers” on page 105. Even though the expected English pronunciation of skycrapers would be sky-crepe-ers, most collectors refer to this first edition as the sky-crap-ers version. Crap being an appropriate adjective for a book with some 60 typographical errors.

The typical story about what happened after the “skycrapers” error was discovered is the one told by a bookseller in their online description (quoting from a copy offered on Abebooks when this essay was first published in 2021): “Reportedly all but 15 of the error-riddled first issue were destroyed.” Another bookseller even added a conflagration to the myth: “Supposedly 12 copies of the first edition survived a fire.” This latter account seems to conflate two stories—the destruction of the first printing and a fire at Encino Press’s warehouse2 that happened before McMurtry’s book of essays was published.

Booksellers can’t be blamed for repeating the story that only 15 copies of the first printing survived. That tale dates from January 1970, just over a year after In a Narrow Grave was published, and the source was the publisher himself, Bill Wittliff. In an interview conducted in late 1969, the University of Texas at Austin student Deborah Detering Pannill reported that “of the 845 copies bound before the error was realized, McMurtry kept 5, the Encino kept 8, and an attempt was made to destroy the rest.”3 That’s how legends begin.

Wittliff told Pannill that the problems began with the expletives McMurtry used in “Eros in Archer County,” an essay on obscene language which predicts in its first line the publisher’s future troubles with the book: “Sex is still a word to freeze the average Texan’s liver, particularly if the Texan is over forty and his liver not already pickled.” While it seems hard to believe now, the publisher had legitimate concerns about obscenity charges, particularly in Texas, which sent someone to jail for selling obscene printed material as recently as 2002.4

According to Pannill’s term paper, Witliff told her that

his regular typographer was unwilling to “contribute to moral decay” and refused to set the type for that language, even though it really isn’t terribly obscene. Wittliff had to resort to a Mexican typesetter [racism in the original] whom he had used before but whose quality was somewhat below standard. After the proofs had been checked, the typesetter took it upon himself to reset type during the slicking process if the slugs were too high or too low. Unfortunately he never mentioned it to Wittliff and his own proofreading was not the best.

Of the 2250 copies printed, 845 were bound before anyone realized there were any errors. The first person to notice was Betty Greene, wife of [Texas author] A. C. Greene. She told Wittliff and they all began to read, carefully. There were over sixty errors. At first Wittliff thought he could salvage some of those printed but finally they decided to destroy the edition and reprint it, saving a few for Wittliff and McMurtry.

The problem is that the physical evidence doesn’t match the story.

The Story Unravels

McMurtry wrote about In a Narrow Grave several times in his numerous memoirs and in his various introductions to the book, but he has shed no light on the errors and how they ended up in the printed book. The only statement by McMurtry that I have found is in a second printing offered for sale by the William Reese Company that McMurtry inscribed, “For Lee, Nobody knows the truth about this book.” McMurtry, whose prose is spare and precise, may well have included himself in that “nobody.”

If you believe the book descriptions on AbeBooks, when McMurtry realized the first printing had so many errors, he “insisted it be withdrawn and reprinted.” Another bookseller embellished that detail: “the erroneous and farcical” error of “skyscraper” (sic) as “skycrapper” (sic) “infuriated McMurtry.”

In fact, there’s no evidence that McMurtry even knew about the errors until after the publisher decided to fix the problem, and late in his life, he still looked back fondly on its original production. In a Narrow Grave, he wrote in his memoir Literary Life, “happened to be the best-designed book I’ll ever have. Bill Wittliff was reaching his peak as a book designer just about then.”5 McMurtry and Wittliff remained friends (frenemies, by some accounts) after the supposed dust-up over the errors plaguing the first printing of In a Narrow Grave. Two decades after that book came out, Wittliff adapted McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove into the memorable miniseries based on the book. That doesn’t sound like a relationship soured by a few typos.

David Streitfeld, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and book collector, also interviewed Wittliff about In a Narrow Grave. According to Streitfeld (conveyed in an email to me), Wittliff assigned the blame to the printer. “Wittliff told me that he had to use a new printer because his regular printer declined to do a book with cuss words. The first printing came in and it had problems.”

Peter Howard, who was one of the great specialists in modern first editions, was skeptical of Wittliff’s efforts to blame the errors on the typesetter (and presumably, had he known about it, his later statements to Streitfeld deflecting blame to the printer). Howard wrote in one of his catalogs, “A recent inspection of three sets of proofs for the book, each representing a successive stage of the production of the book, revealed the presence of the determinative errors in each case.”6

The only set of page proofs I have located—the first typeset version of the text delivered by the printer—did indeed include the “skycrapers” error (sold most recently in 2018 by Heritage Auctions for $2750). If the errors survived three sets of proofs, then they weren’t introduced by the typesetter or by the printer after the proofs had been approved, as Wittliff long claimed.

In Peter Howard’s account, he adds a new detail, “The few copies which had been distributed for sale, chiefly to Austin bookshops, were picked up by Wittliff. The press kept eight copies, the author five, and the rest were deep-sixed in a dry well behind the old Encino offices and bulldozed over with fill.” (First the books were supposedly burned in a fire; now we hear they were drowned in a well. Dramatic stuff!)

Nevertheless, Peter Howard expressed some doubts about Wittliff’s story. He described a copy he had for sale as “one of the mysterious ‘few’ which evidently, according to Wittliff, escaped the recall in spite of his genuinely conscientious efforts to retrieve all copies.” His quotation marks around “few” and his general tone suggest he thought Wittliff had oversold the scarcity of the book. Howard noted that he had obtained another copy of the “skycrapers” printing from a book reviewer who got it direct from the publisher, adding reviewers and Austin bookstores to the potential list of recipients of the error-filled copies.

According to Streitfeld, who asked Larry McMurtry about the initial publication of In a Narrow Grave, the author also took Wittliff’s tale of retrieving copies of the book with a grain of salt. “McMurtry does not believe this,” Streitfeld told me in an email. “He thinks Wittliff was too cheap to throw away a couple thousand books.” Or even all the 845 bound on hand when the errors were discovered.

Physical Clues to What Really Happened

A unique copy of In a Narrow Grave in my possession at the time I originally wrote this essay offers a hint of what probably happened after Wittliff realized how poor the copyediting had been (Given that at least three states of the page proofs had the error, the responsibility for poor copyediting was the fault of Encino Press and not the typesetter or the printer).

In her essay, Pannill wrote, “At first Wittliff thought he could salvage some of those printed but finally they decided to destroy the edition and reprint it.” My unique copy has the “skycrapers” error on page 105, but it does not have the errors on pages 56, 134, or any others of the dozens of pages with typos. It also has a second page 105 with the corrected text (this is printed on a bifolium, or two leaves with the pages 105 to 108).

Getting a bit into the weeds, this extra sheet makes for 10 leaves in the eighth gathering (a gathering is a unit of pages sewn together when a book is bound). Typically in modern books, gatherings have multiples of four leaves, most commonly 8 or 16. The only way to make a gathering of 10 leaves is to print a standard gathering of 8 leaves and add a single sheet, folded to make two leaves or four pages. This is hand bookbinding work.

My unusual copy is strong evidence that when Wittliff told Pannil that he “thought copies could be salvaged” he meant that the press attempted to replace the pages with errors with corrected sheets in the unbound copies. According to Pannill’s account, only 845 copies had been bound when the problems were discovered, leaving some 1400 in unbound sheets. In the case of my copy, they failed to remove the original sheet at the center of the gathering with “skycrapers” on page 105 and instead added the corrected sheet to the gathering, leaving both the corrected and uncorrected “skycrapers” page in the book. How many of the unbound copies were fixed before Wittliff gave up and reprinted is anybody’s guess.

Errors on the Dust Jacket of In a Narrow Grave

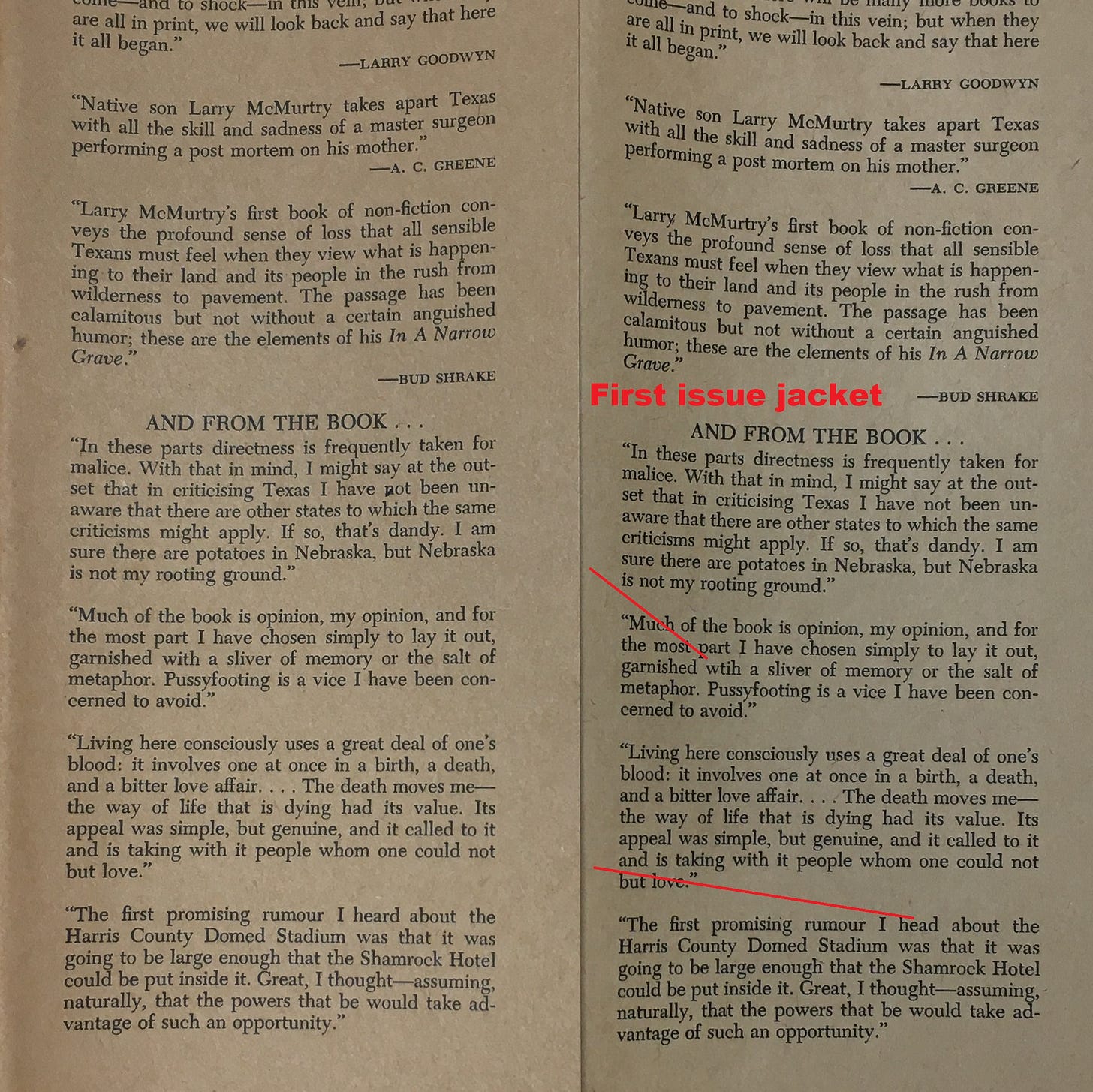

Despite devoting two pages to the history of In a Narrow Grave in his Serendipity Books catalog listing, Peter Howard does not mention that the printing errors extend to the dust jacket as well. There are two typos on the front flap, “wtih” in paragraph 5, line 3, and “head” for “heard” in the first line of the last paragraph. Both of these errors are direct quotes from the text; ironically, the book text for these passages is correct, even in the “skycrapers” copies. Either Witliff didn’t notice the jacket copy errors when he started fixing the errors in the book or perhaps by that time, he was tired of spending time and money on the project. He used the jackets with typos on both the “skycrapers” copies and on the corrected second printing.

How Many Copies of the First “Skycrapers” Printing Are There?

In his catalog entry, Peter Howard said he had accounted for twenty-two copies of the “skycrapers” issue while noting he had “seen five times as many of the corrected printing over the last decade.” That’s just one bookseller in the pre-Internet era who was able to identify more copies of the book than the publisher said survived in total.

At the time of this writing (2021), there are five copies of the first “skycrapers” printing for sale on AbeBooks. That compares to seven copies of the signed, limited edition, which was 250 copies. That proportion suggests there are maybe 200 surviving uncorrected first printings. However, the book is much scarcer in the auction records, with just one copy in the last 10 years, compared to seven or eight of the signed, limited edition. My guess is that the real number is somewhere between 100 and 200 surviving copies, not all in collectible condition.

To summarize:

The physical and documentary evidence strongly suggest that the publisher did a poor job with the proof reading of In a Narrow Grave, allowing dozens of errors to pass unnoticed in the first printing. As many as 845 copies were bound with the errors. As many as 1400 copies remained unbound when the errors came to light.

The publisher’s initial response was to print corrected pages and replace them in the unbound copies. How many copies this was done for is not known, but probably not very many. In the end, the publisher scrapped most of the unbound first printing. Of the 845 bound with errors, most were destroyed but it is likely that 100 to 200 copies survived.

The publisher ordered a second, corrected printing but did not change the copyright page to reflect this new print run. Two hundred and fifty copies of this second printing were bound as signed, limited editions. (Publisher’s track printings as an indicator of sales; for the publisher, there is no reason to mark a book as a second printing when the first printing was mostly destroyed).

Bibliography of In a Narrow Grave

Uncorrected Proofs before publication

0.a. Long galley page proofs

7-1/2 by 25 inches. 61 leaves. With the uncorrected skycrapers text. One copy in the auction records, sold by Heritage in 2016 and Christie’s in 1996. Dated July 22, 1968.

0.b–c. [Two other states of the proofs, reported by Peter Howard but not described sufficiently to identify here]

First edition (first printing)

1.a. First printing, first state.7

Book: Skycrapers text on page 105, line 12; “in in” on page 56.2; and duplicated text in the second paragraph on page 134, and many others. Collation: [1–5]8 [6]10 [7–12]8

Binding: Yellow cloth binding; paper spine label; author's signature stamped in black on the front board.

Dust Jacket: Dust jacket printed on tan Kraft paper; $7.50 price on front flap; “wtih” on line 5 of the fifth paragraph on the front flap and “head” for “heard” in the first line of the last paragraph on the front flap.

About 2250 copies printed; 845 copies bound; most scrapped. Perhaps 100–200 copies survive.

1.b. First printing, first state, no spine label variant

Book: Same as 1.a.

Binding: Same as 1.a., but without the spine label (whether these copies have McMurtry’s signature stamped on the front cover is not known to your bibliographer).

Dust Jacket: No dust jacket.

According to Peter Howard’s catalog description, “The press kept eight copies... usually bearing cryptic inscriptions by the publisher. These copies lack the printed paper label on the spine, and do not have the dust jacket unless the purchaser supplied one from another copy.”

1.c. First printing, hypothetical second state (indistinguishable from 2.a.)

Book: Errors fixed by replacing the leaves with errors with corrected sheets. These leaves were (hypothetically) replaced before binding, and would be nearly impossible to distinguish from the second printing.

Dust Jacket: Same as 1.a, with errors.

This issue is based on the physical evidence of one copy with p. 105 in both states describe above, plus the documentary evidence; but sometimes one is enough.

Second Printing

2.a. Second printing, trade issue. November 1968.

Book: No printing letter on the copyright page; the correct “skyscrapers” on line 12 of page 105; other errors fixed. Same collation as 1.a.

Binding: Same as 1.a.

Dust Jacket:

First state, same as 1.a.

Second state (technically second printing jacket), “with” and “heard” spelled correctly on the flap. The paper is brown Kraft paper, noticeably darker than the first printing jacket. Also priced at $7.50.

I have had a copy of 2.a. with the second state jacket. Most copies of the second printing, trade issue, have jackets with errors. It is unclear whether the jackets were fixed at the same time that the books were reprinted or if the jackets were fixed only with the “B” printing (see below). Under either scenario some copies of 2.a. could have had the corrected jacket from the get-go. Or such copies could have had jackets married by collectors or dealers from later printings.

Note: This second printing of In a Narrow Grave is sometimes called the first edition, second issue. This is incorrect. Issues occur within a single printing. When the first printing and the second printing are different, they are just separate printings. See John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors entry for “Issues and States” on page 134 of the online version, particularly the notes at the end which refer to impressions (the British word for printing).

2.b. First limited edition (from second printing sheets)

Book: Corrected text printed on Artlaid paper.

Binding: Quarter-suede leather and paper-over-boards, reproducing the art on the trade dust jacket. Signed by McMurtry on the half-title; with a tipped in limitation sheet at the front, numbered in ink.

Slipcase: Apparently covered with the same cloth as the regular trade edition and stamped with McMurtry’s signature on the front cover. No dust jacket issued.

Limited to 250 signed and numbered copies.

This version was almost certainly issued to the public after the second printing (2.a). The publisher was desperate to replace the defective first printing copies. Wouldn’t they do that first and then put out a special signed, limited edition?

If there were lettered or presentation copies, I haven’t seen any reference to any.

Later Printings

Third printing with a “B” on the copyright page. Same binding as the first printing. Corrected text in book and jacket. $7.50 jacket price.

Fourth printing with a “C” on the copyright page. Corrected text in book and jacket. $7.50 jacket price. Seen in two bindings: a) brown cloth, stamped in gilt on the spine; no stamping on front cover; and b) apparently the most common, a tan binding with brown streaks, stamped in black on the spine, with no stamping on the front cover.

Some copies of the fourth printing have price-increase ($12.50) and ISBN stickers on the front flap. In 1979, Encino Press was still advertising the book for $7.50 in the Texas Monthly.

McMurtry, Larry. Literary Life, p. 17. Simon & Schuster published In a Narrow Grave in paperback in 1971. Encino Press sold hardcovers for more than a decade.

“Working long days, they were able to move the press to its own space on South Lamar Street in 1968. Unfortunately, that was the same year the Whitley Company warehouse fire destroyed most of their book stock.” Quoted from “A Brief History of the Encino Press,” retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20210805205406/https://thewittliffkeystone.com/2018/12/05/a-brief-history-of-the-encino-press/ on January 31, 2024.

Deborah Detering Pannill 46-page term paper, “The Encino Press: A Regional Publisher, Its History and Its Books,” written in 1969, is the best contemporary source about In a Narrow Grave.

As recently as 2002, a Texas court convicted Jesus Castillo for selling a comic book. The Encino Press used McMurtry’s strong language as a selling point in a review of the book planted in the Austin American Statesman (November 24, 1968). The glowing article was written by A. C. Greene (husband of the Betty who found the errors). “The actual publication took a good deal of bravery, for McMurtry’s vocabulary, while essentially detached and cool is godawfully precise in its use of certain popular words, terms and descriptions not hitherto put into print by a Texas publisher.”

McMurtry, Larry. Literary Life, p. 17.

Ed Smith kindly shared his photocopies of the relevant pages with me, but neither of us have the rest of the catalog. In a Narrow Grave is item 417; I don’t know which catalog this was or when it was published.

Reasonable people could disagree about whether the variants are states or issues. Under the definition used by John Carter in his ABC for Book Collectors, they would be issues because the changes were made after publication. I find Thomas Tanselle’s argument, made in Descriptive Bibliography (2020), more convincing. In Tanselle’s formulation, buiding on Bowers’s work published in 1949, issue should be used to describe distinct publishing units and state should apply to efforts to perfect the books