Where Do Books Go? Thoughts on Provenance

Plus, a short list of new arrivals from Downtown Brown Books

Paying the Bills

A short list of new arrivals just posted to my website, including a collection of poems by the Lebanese American poet-artist Etel Adnan, illustrated with an original pastel drawing; several X-Ray Book Co. publications; and a signed H. G. Wells novel with a handwritten draft telegram laid in.

Thoughts on Provenance

When did book collectors decide that we wanted pristine books that looked like they just came from the publisher?

Collectors frequently contact me about potential purchases to confirm that dust jackets aren’t price-clipped and that there are no ownership names, gift inscriptions, or bookplates inside. It’s easy to think that collectors have always wanted such pristine copies. But that’s not true. It’s definitely a late 20th century phenomenon.

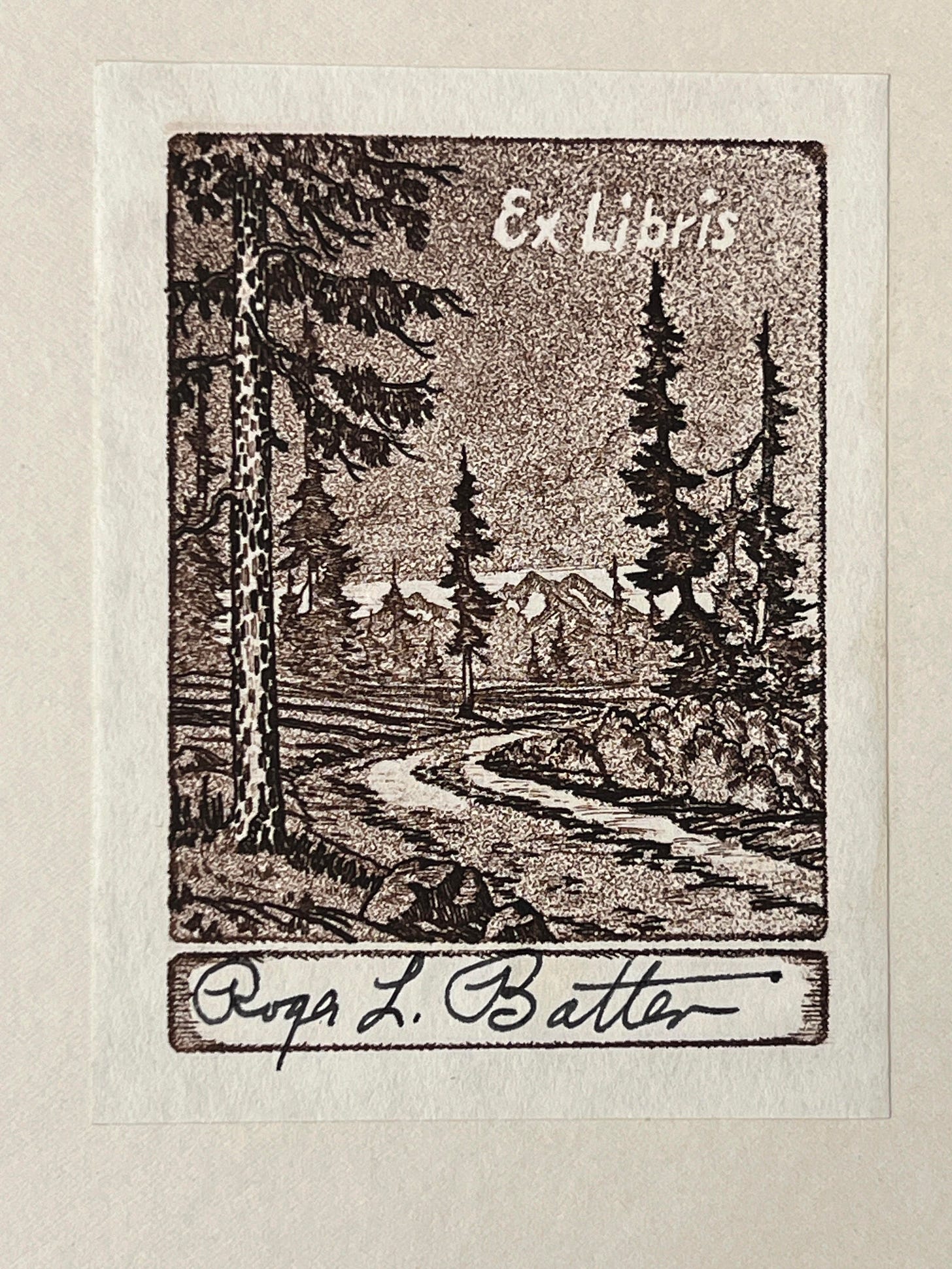

With few exceptions, the collectors of earlier eras had their books rebound in pretty leather and marbled paper, which is why collecting 19th century and earlier books in original condition is so difficult today. The copies collectors want now were books that slipped through the cracks and never made it to a bindery. Bookplates and ownership signatures on rebound books didn’t seem to bother our predecessors, perhaps because they were placed on parts of the book that weren’t original anyway, and they could easily be removed by simply having a book rebound again.

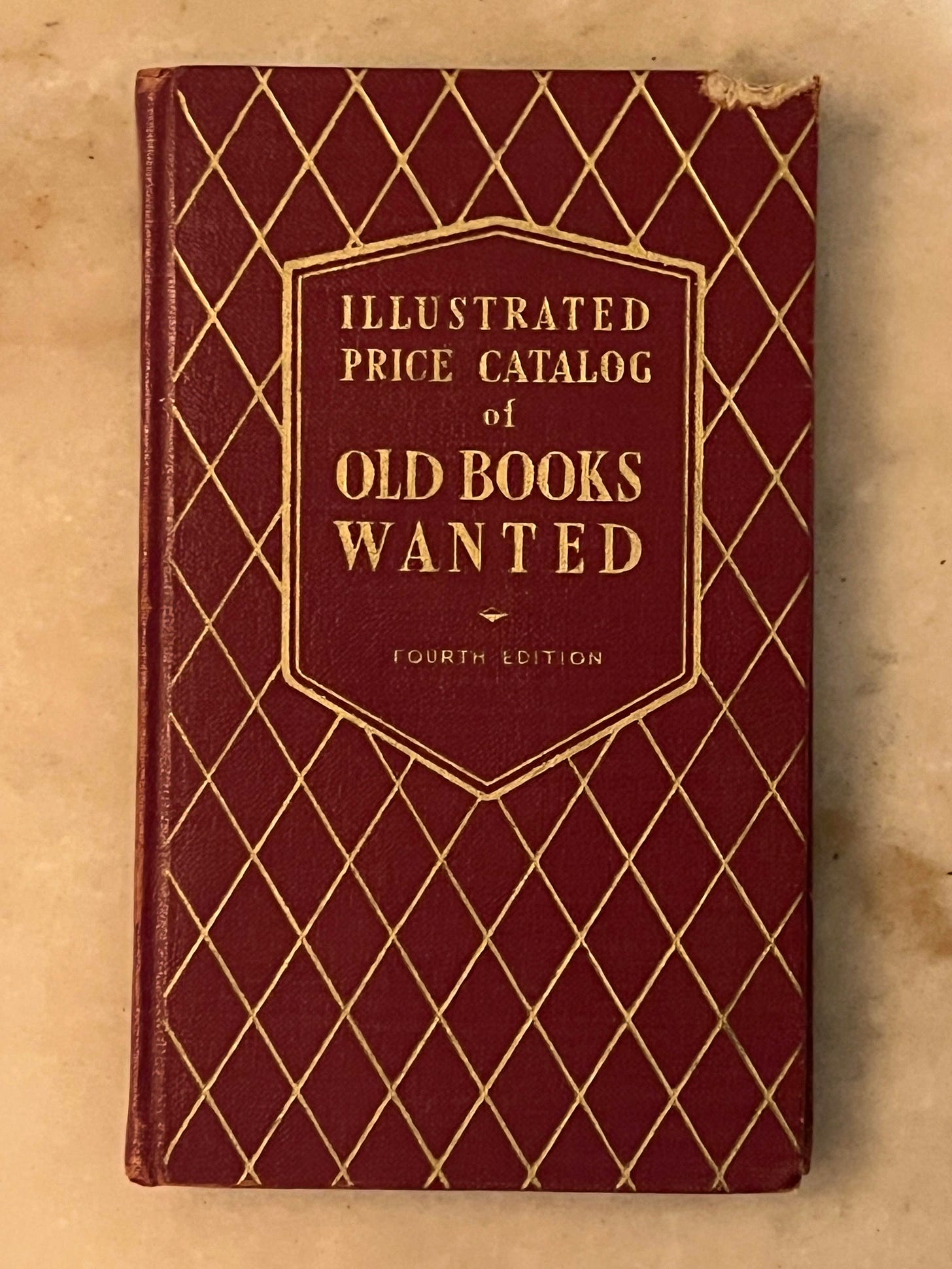

One of my favorite reminders of how collectors used to think (as reflected by what dealers were looking for) is a funny little book from 1938 that I keep on my reference shelves. It is titled Illustrated Price Catalog of Old Books Wanted, which the American Book Mart (ABM) of Chicago put it out annually for several years seeking to buy rare books from the unsuspecting public.*

ABM seems to have been especially keen to locate a copy of Edgar Allan Poe’s rare first book, Tamerlane, as the title page of the first edition is reproduced as a frontispiece in my copy (They weren’t successful; no previously unknown copies surfaced during the Great Depression, although a lot of families could have used the $5,000 ABM was offering).

I don’t know much about the American Book Mart, but one can find newspaper references to it back to the 1880s, when they promoted some sort of book rental program. By the late 1930s, they were advertising heavily in newspaper classified sections around the country and in the backs of magazines like Popular Mechanics and Life. For a dime they’d send you their want list. I assume they tried to upsell the book-length Old Books Wanted to anyone who contacted them from a magazine, or perhaps that’s what you got for your ten cents. ABM also employed a Mrs. Evelyn O’Malley as a traveling rare book buyer; she was, I expect, the only woman doing that job at the time.

Old Books Wanted is a snapshot of the book market at a point in time. By the publication of my fourth edition in 1938, the preference for publisher’s cloth and drab boards had taken hold: “Our prices are for books in their original bindings,” the American Book Mart advised its potential suppliers. “Even though the original bindings may be a cheap paper or cardboard cover, a book in that binding is nearly always more valuable than one...in an expensive leather binding.”

What’s telling about collecting trends at the time is that the section on book condition makes no mention of dust jackets, even though books by Willa Cather, Ernest Hemingway, and Edith Wharton were on the ABM want list. Likewise, the condition section, which employs ALL CAPS and bold type for emphasis, makes no reference to bookplates or owner signatures. Few booksellers did in those days because hardly anyone thought that dust jackets or ownership markings mattered much for condition.**

Personally, I don’t care much for owner signatures or large bookplates, particularly messy signatures and pre-printed bookplates with the owner’s name handwritten in ink. I especially don’t like them when they are glued down on patterned endpapers.

On the other hand, more and more often I find myself wondering about the paths books take from owner to owner, and I wish there was a more elegant way to mark a book’s journey through time. Booksellers have tried various ways to preserve this “provenance.”

Several years ago, I commissioned a letterpress printer to print small two-color bookplates for books from the library of the science writer Stephen Jay Gould.

Just this week, the firm founded by Peter Harrington announced the acquisition of the collection of Winston Churchill’s bibliographer, Ronald Cohen. They had Cohen sign each book in pencil, presumably so that buyers could choose to erase his ownership from the book’s history, if they valued pristine condition over provenance.

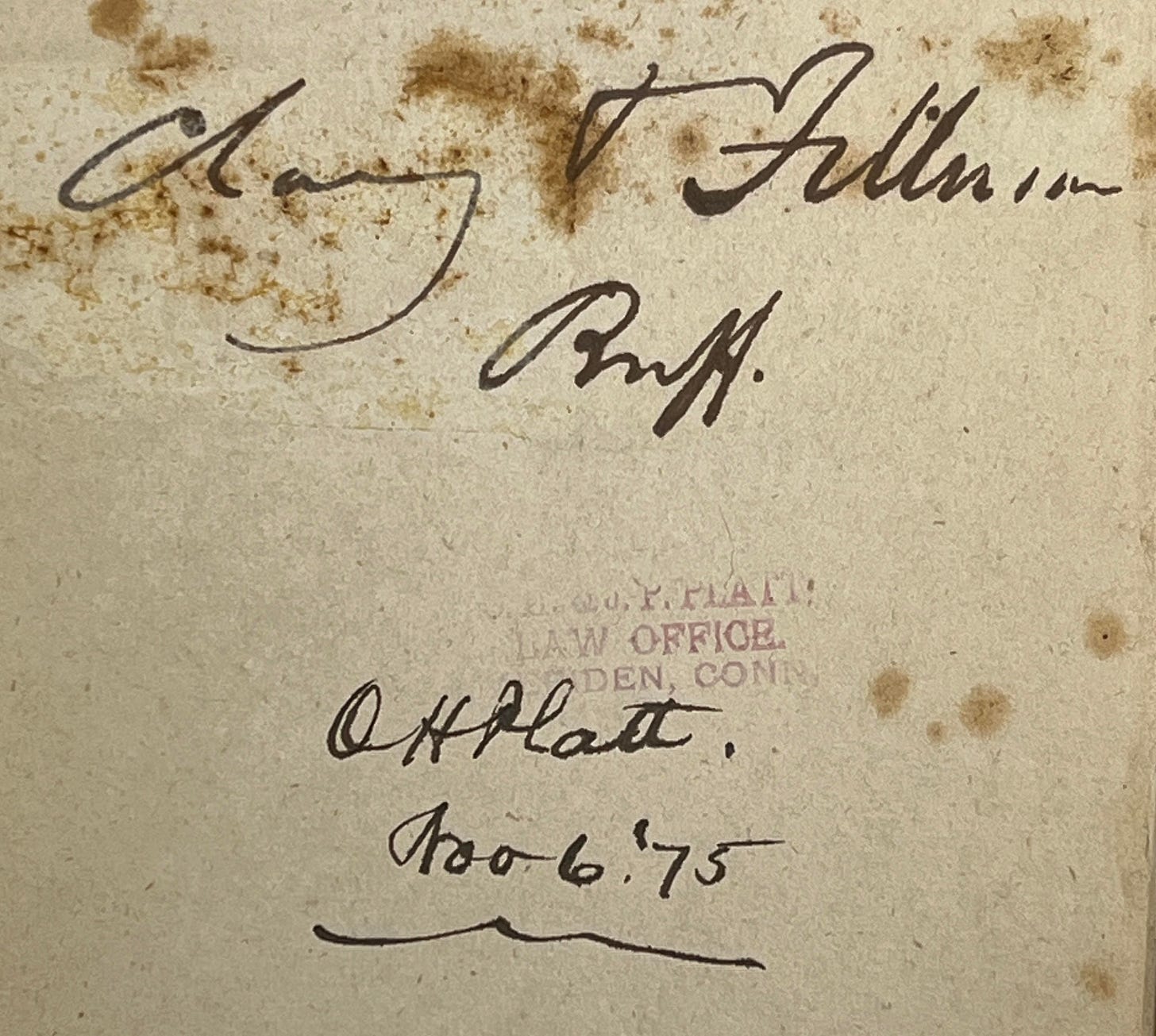

One of the most my favorite books on this week’s new arrivals list has interesting ownership markings, tracing its history for most of a century. The two-volume legal set belonged to Millard Fillmore (his name is in gilt at the base of the spine). Then it seems to have gone to the library in the office of his first law practice (Clary and Fillmore is written in ink on the pastedown). At some point, about the time Fillmore was elected president, he affixed a bookplate with just his name. After Fillmore died in 1874, his heirs dispersed his library. The Connecticut attorney Orville Hitchcock Platt acquired the set and signed his name along with the date, Nov. 6, [18]75. For good measure, Platt added a law office stamp in purple ink. Platt won a seat in the US Senate in 1878 and served until his death in 1905. Presumably this book stayed in Connecticut as it has no Washington, D.C. markings.

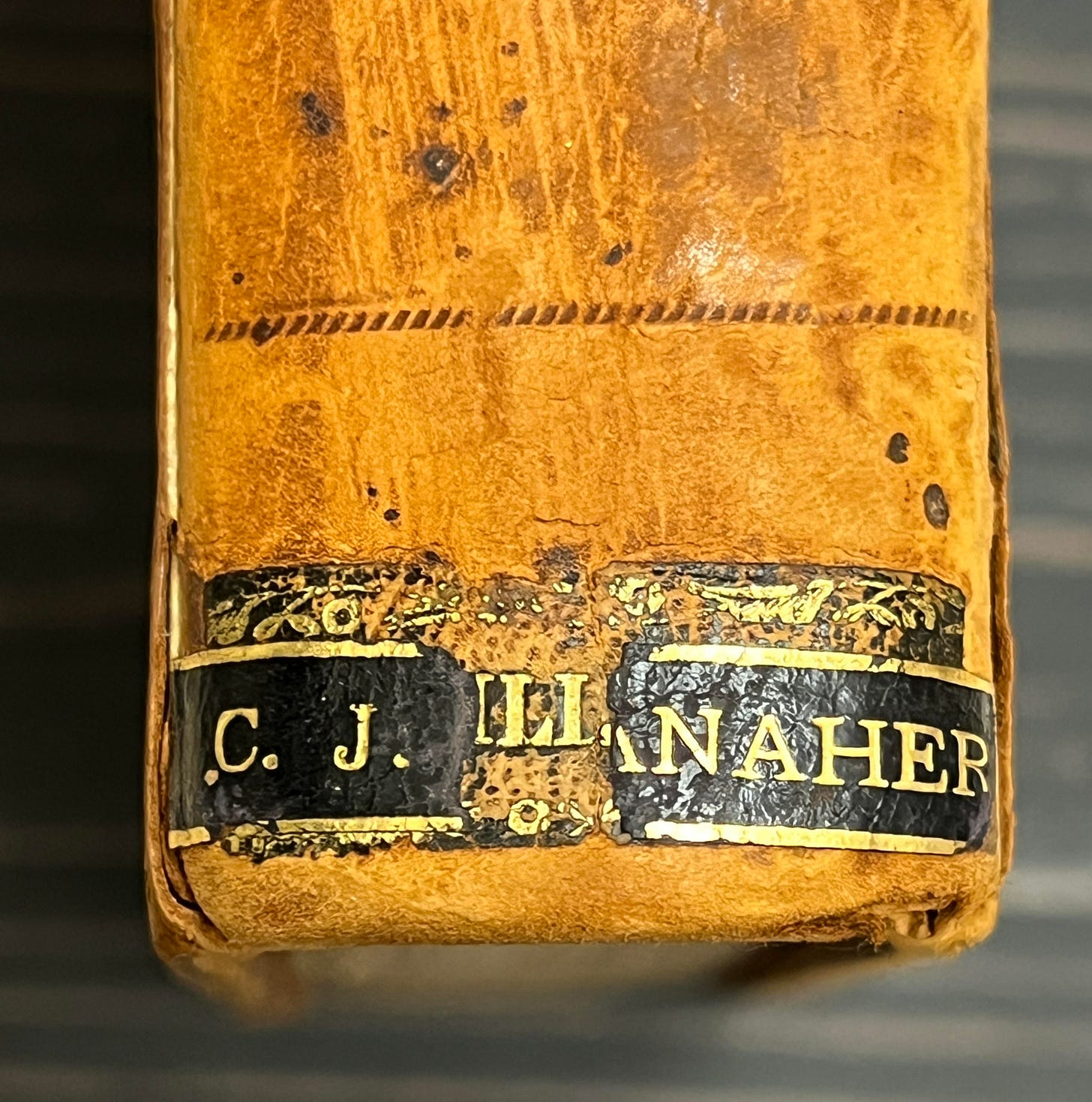

In the early 20th century, another attorney, C. J. Danaher***, acquired this set and pasted a leather label with his name over “Fillmore” on the spine of each volume. At that point, the trail went cold until I acquired it from a bookseller outside of New Haven, Connecticut.

Perhaps the owners after Danaher felt intimidated about adding their name to a book that already had the markings of an American president and a powerful Republican senator. I might feel that way, too

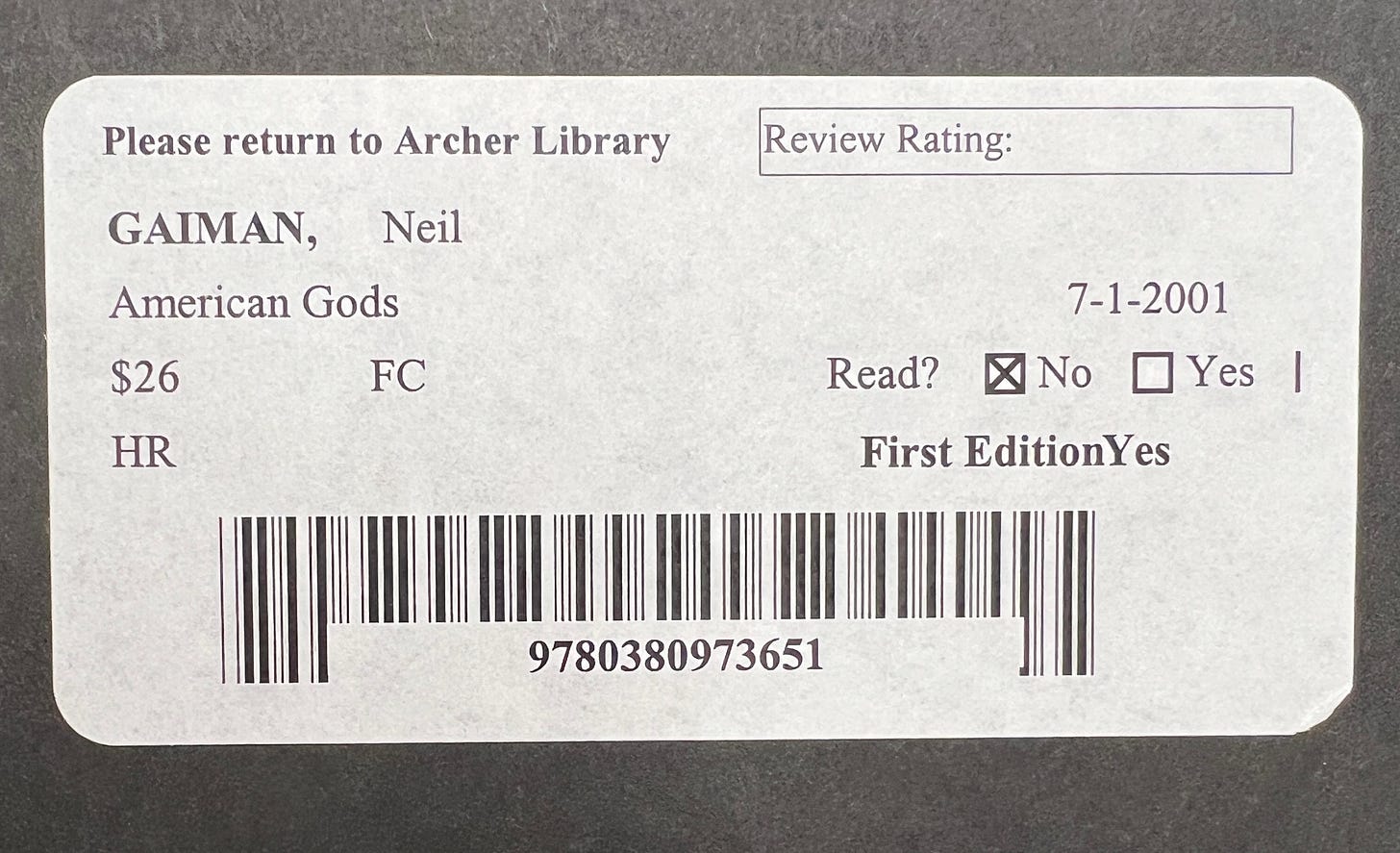

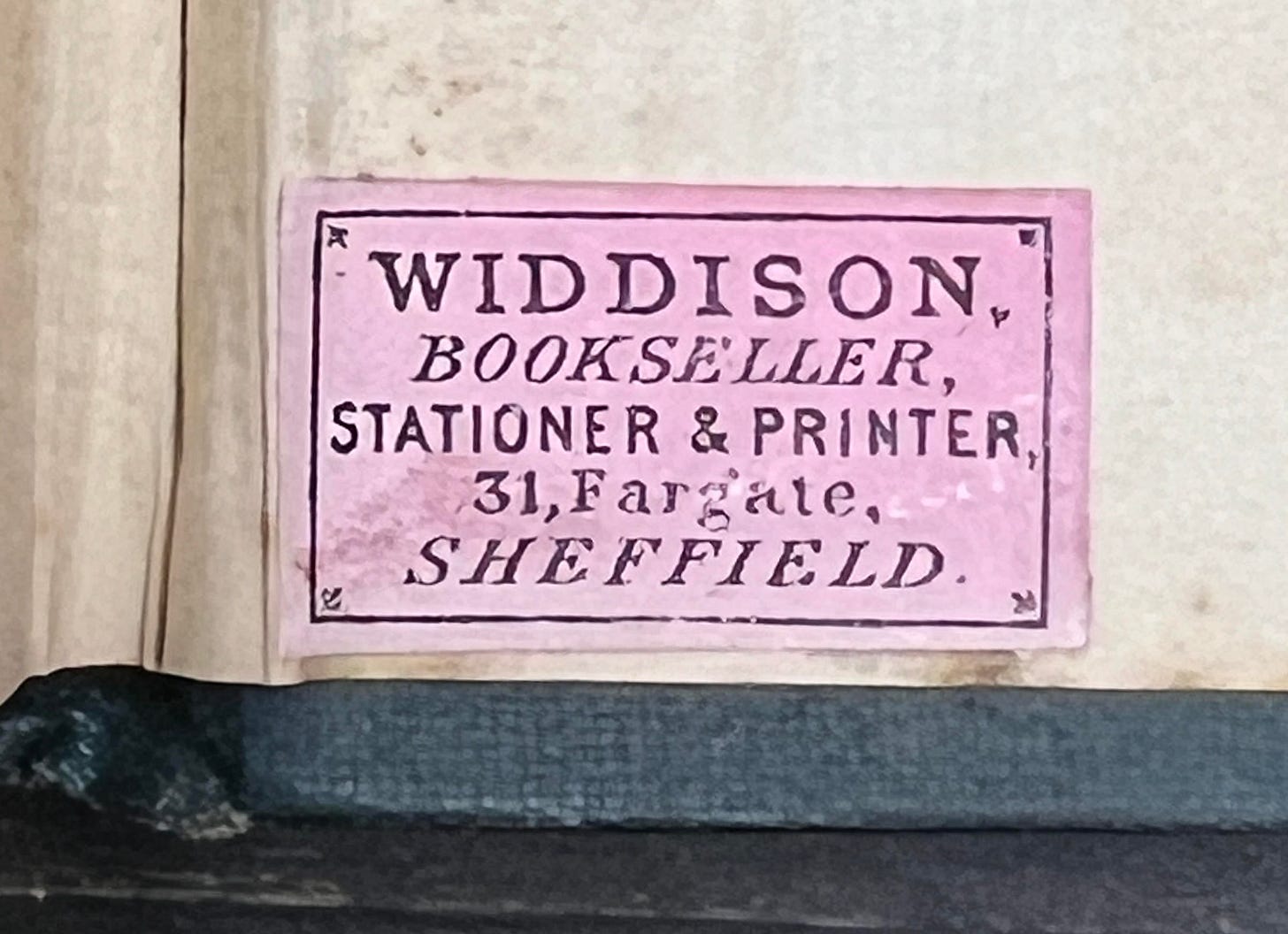

Instead of bookplates or penciled ownership signatures, what I’d really like to see is the return of small book labels of the kind once widely used by bookstores and binderies. They usually occupy less than a square inch of space and if artfully designed, would not significantly detract from the value of a book. I don’t know who could print such a label. Fine engraving and handsetting minute pieces of lead type are something of a lost art, but I for one would like a way to record the ownership of books as they pass through history.

—Scott Brown

Notes

* Since the American Book Mart only published these books wanted lists for a few years, I assume that the costs of the advertising campaign exceeded the profits from the rare books the public sold to them. In the 1950s, a fellow named Van Allen Bradley improved on ABM’s idea about turning old books into money via the general pubic. He published Gold in Your Attic, a book like Old Books Wanted, with lists of valuable titles and their values. Bradley didn’t hassle with trying to buy the old books, he simply sold his new one, over and over, under at least six different titles. In various editions and a second generation of compilers, Bradley’s work stayed in print until the Internet era.

** Book dealers are not in agreement over whether fine or very fine should be the highest grade. Comic book collectors use condition terms that are mapped to a 10-point scale. Very Fine is 8.0 on that comics scale, and it is roughly equivalent to very fine in rare books. Comics people are such fanatics about condition that they have eight grades higher than very fine, most of which can only be differentiated using a magnifying glass. Yet in the field of vintage (Golden Age) comics, the same comics collectors who will argue endlessly online over whether a particular flaw is more or less than a sixteenth of an inch (the dividing line between some grades), don’t count ownership markings at all in condition grading, even when they are on the front cover. We book collectors, who are ordinarily more forgiving of condition than our comic-book collecting cousins, would mark a book down at least an entire grade if a previous owner wrote a name inside a book, let alone on the front cover.

*** The spine labels with Danaher’s name were chipped and missing letters. Between the two labels I had “C. J. ___anaher.” I thought this would be a perfect problem for artificial intelligence because there’s virtually no way to effectively search the Internet for the last part of a word.

I asked Bing’s Co-pilot, “Can you give me a list of surnames ending with the letters anaher?” It came up with eight options, in each case supplying the Gaelic origin. None of the eight were right (yet on the strength of this indifferent performance of its artificial intellegence offerings, Microsoft has recently gained hundreds of millions of dollars in market capitalization).

I asked ChatGPT the same question. It gave me useless results like “Tanner”, which doesn’t end in -anaher at all. I phrased the question slightly differently and asked ChatGPT again. This time it gave me nonsense surnames like Zinaher.

I combined one of ChatGPT's nonsense answers, Dinaher, with the structure of answers provided by Bing co-pilot. I googled C. J. DAnaher, and he turned out to be an attorney in Connecticut in the early 20th century, which is why I have attributed ownership of these books to him.

As someone who checked out a lot more library books than owned books; I can say I get a kick when I find a library that still has a check out card in the back. It was always fun to see how near or far the last check out dates were. I haven’t seen one in probably the last five years.