What Has Happened to the First Edition?

An essay, with links to new arrivals in Downtown Brown Books' science fiction section.

Is the First Edition Dead?

Perhaps you’ve seen a book described this way: “first edition, fourteenth printing.”

For many antiquarian booksellers of my generation, who can remember the era before the Internet, such descriptions sting our eyeballs.

The subject of “first edition, later printing” came up recently when a bookseller friend (who has been selling books for about ten years) recounted aninteraction he had with a well-known old-school bookseller. My friend had listed online a signed copy of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 as a first edition (fourteenth printing) for $1800. The venerable bookseller ordered it and then canceled the order when he realized it was a fourteenth printing. My friend asked me if his description was wrong.

As it happened, I was working on this essay already.

Traditional booksellers would say definitively that first edition, fourteenth printing is an incorrect description because it’s an oxymoron. First edition is shorthand for first edition, first printing, and thus first edition, first printing, fourteenth printing makes no sense. Traditional booksellers with long memories might also add that statements like first edition, later printing first came into widespread use by shady Internet sellers looking to hoodwink unsophisticated collectors.

The use of first edition as shorthand for first edition, first printing is not something I and my old-school colleagues made up. This definition was included in the very first edition of John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors back in 1952. It has been included in every subsequent edition over the last seventy years with the note that “this has been taken for granted for so many years that it hardly needs saying.”

ABC, now in its ninth edition, remains the one book all booksellers and book collectors should have. It is the starting point for definitions of all things bibliophilic, and it has been given the imprimatur of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB), the worldwide fraternity of rare book dealers, which has made an edition of ABC free for anyone to download.

Yet we come back to the fact that both my friend and his venerable customer are members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (ABAA), the leading American membership organization for rare book dealers (members of the ABAA are also members of ILAB). The ABAA’s Code of Ethics requires booksellers to “be responsible for the understanding and use of the specific terminology of the trade.” No term is more fundamental to bookselling than “first edition,” yet with this copy of Catch-22 we have two ABAA dealers misunderstanding each other over the phrase.

Clearly something big and maybe generational is at work.

I asked a number of collectors and dealers their thoughts on describing books as first editions, later printings, and I got lots of strong opinions. A frequent comment was that dealers who described books that way are amateurs or inexperienced. But one collector offered the opinion that it was an “abomination” that leading dealers had also adopted the practice. Indeed, this weekend on the ABAA’s blog highlighting books offered for sale by members I found a book described as a “first edition, second printing.” Even the ABAA’s head office appears to sanction the practice.

To me, the big problem with the use of the phrase first edition, later printing is that it lacks intellectual rigor. John Carter, if I may inject a bit of bookselling history, was the rare combination of accomplished bookseller (he put out some of the first catalogs devoted to subjects that seem obvious and routine today—detective fiction and contemporary science—while working for Scribner’s) and scholarly bibliographer (his first book was a devastating takedown of a respected bookman who had been forging rare pamphlets for decades). In short, he knew his stuff because he had been working for decades at the highest levels as a scholar and as a dealer. John Carter is not to be trifled with, and his definition of edition was carefully thought out.

If the book trade allows descriptions like first edition, fourteenth printing for a 1960s reprint of Catch-22, when does first edition, nth printing stop making sense? To be useful, a term like first edition should clearly explain what is—and is not—encompassed by the term. To my knowledge, none of the proponents of the use of first edition, later printing have published guidelines about how to correctly use this terminology, which makes it hard for those of use who don’t think that way to understand what, exactly, they mean.

Consider The Catcher in the Rye, by J. D. Salinger, first published in 1951.

The novel, sought by many collectors, is still in print in hardcover from the original publisher, with the same cover design and the same typesetting. You can buy one today and under the logic that allows for first edition, fourteenth printing, you are still getting a first edition seventy-two years later. Right now on eBay you can buy copies marketed as first editions, later printings, including a 3rd printing, a 26th printing, a 27th printing, a 52nd printing, etc. Apparently it will never end until the hardcover goes out of print.

One bookseller I asked about where the definition of first edition ended said it was like obscenity, “I know it when I see it.”

Others fall back on the definition from the field of descriptive bibliography, generally recited as “an edition is all copies of a book printed from substantially the same setting of type.” If the typesetting (meaning page layout for modern books) doesn’t change from the first to the fourteenth printing, all of those printings are part of the first edition.

That definition was formulated by Fredson Bowers in his 1949 book, Principles of Bibliographical Description (his exact definition of edition was “the whole number of copies printed at any time or times from substantially the same setting of type-pages”).

I asked booksellers what they thought “substantially the same” meant when it came to changes separating one edition from another. I got answers like the addition of an ISBN to a non-ISBN book, a new introduction, a new binding, and some revisions to the text.

Those answers might seem reasonable, but they are wrong, and this is why book collectors and rare book dealers have no business even thinking about the definition of edition developed by descriptive bibliographers.

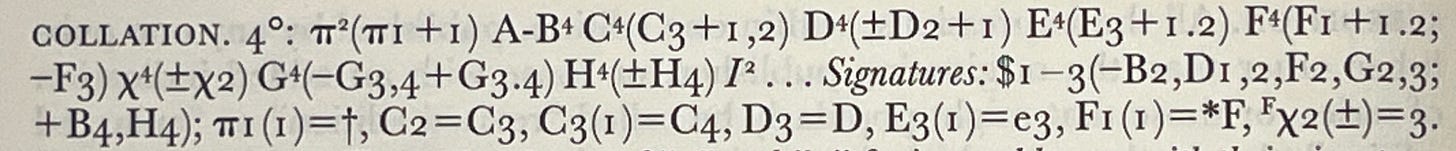

Descriptive bibliography is a very technical and complex subject that can look closer to quantum physics than to literary criticism. Scholars in the field argue over descriptions of books that look like this:

Fredson Bowers’s use of the word substantially left some room for ambiguity that Philip Gaskell, the author of a subsequent definitive work on descriptive bibliography, answered in his 1995 book, A New Introduction to Bibliography. “As to the meaning of ‘substantially the same setting of type,’” he wrote, “there are bound to be ambiguous cases, but we may take it as a simple rule of thumb that there is a new edition when more than half the type has been reset” (emphasis added).

Adding an ISBN to a book, or a new chapter, fixing a few typos, or even reissuing the book in paperback using the same layout as the hardcover are changes that are not even close to being more than half the book and therefore bibliographers would not consider those books a new edition. ABC for Book Collectors goes on to point out that descriptive bibliographers count facsimiles and even photocopies as part of the same edition (no change to the page layout!). To that list of horrors I would add book club editions and Taiwanese piracies to the list of books that would typically count as first editions under the descriptive bibliographer’s definition.

Even the most fast-and-loose Internet bookseller would think twice before describing a photocopy of a first edition as a first edition.

Anyone unwilling to use all of the descriptive bibliographer’s definition of edition should avoid using any of it.

But we are still left with the uncomfortable fact that first edition, later printing is found routinely even at the highest level of the book trade.

To me, using descriptions like first edition, fourteenth printing seems shortsighted. It tosses out a century of tradition to make it a bit more likely to sell the handful of books in every bookseller’s inventory that are not first printings. In the effort to sell the odd later printing as a first edition, booksellers are weakening the meaning of first edition for all their books.

Part of the reason booksellers call later printings first editions is practical. Collectors today are willing to buy later printings, and online first edition is starting to mean something more like vintage instead of first edition, first printing. If a seller doesn’t call their book a first edition, their chance of selling it online goes way down. So I can understand the financial pressures that push dealers to use first edition, later printing—booksellers are, after all, sellers of books and knowing how to market to one’s customer base is an essential skill. Where there is demand, you can count on booksellers to supply it.

In the reality of online marketplaces where books called first editions are more visible than books described without that term, even traditionalists like me might need to allow some modification of the use of first edition.

Perhaps the best alternative is describing a book as a “fourteenth printing of the first edition,” which seems more honest than “first edition, fourteenth printing.” It places the emphasis on the fact that the book is a later printing rather than diminishing the meaning of first edition.

So to return to the original question, is first edition (fourteenth printing) wrong?

In short, yes, I’d say it’s wrong, and I’d have the weight of history, tradition, and scholarship behind me. I’d also say that fourteenth printing of the first edition is better. But the mercenary answer to the question would be “it’s fine, because collectors respond to it.” While I was busy writing this essay for free, my friend sold his first edition, fourteenth printing of Catch-22. He got $1800, and all I ended up with is this Substack post.

So it goes.

PayPal Follies, or What It Is Like Dealing with Our Robot Overlords

A couple of days ago I paid for a book using PayPal. I included the message, “Martin Mars—thanks,” mostly so I would remember what the transaction was for when I do my books at the end of the month. The Martin Mars is an airplane.

For some reason, this $200 transaction set off alarm bells at PayPal, and they froze my account until I supplied the following information: “The date of birth for Martin Mars.” (NB: This was not a phishing scam, it was really PayPal.)

I responded with the truth, that I didn’t know the date of birth for Martin Mars and that even if I did, it would be inappropriate for me to provide someone’s birth date to PayPal or any other random Internet site.

PayPal rejected this answer.

So I tried again, repeating that I really didn’t know the answer.

PayPal rejected that answer, too.

I asked my wife for her opinion, and she said to just give PayPal a date. I called a friend who suggested telling PayPal that it was trick question because Martin Mars was an airplane.

I had to take this ridiculousness seriously because PayPal had frozen just short of $1000 of my money, and the company was preventing me from taking payments on my website.

I took my wife’s advice. According to Wikipedia, the Martin Mars’ first flight was June 23, 1942.

I entered 06/23/1942 on PayPal’s online form, and in minutes my account was unfrozen.

As always, excellent newsletter.

No, Scott, you ended up with a Substack post full of wisdom, truth, accuracy and tradition. This is worth more than A LATER PRINTING of just about any book. 8^)