Sorry, Your $2 Cat in the Hat Is Not a First Edition

Getting deep in the weeds about the first printing of a beloved children's book

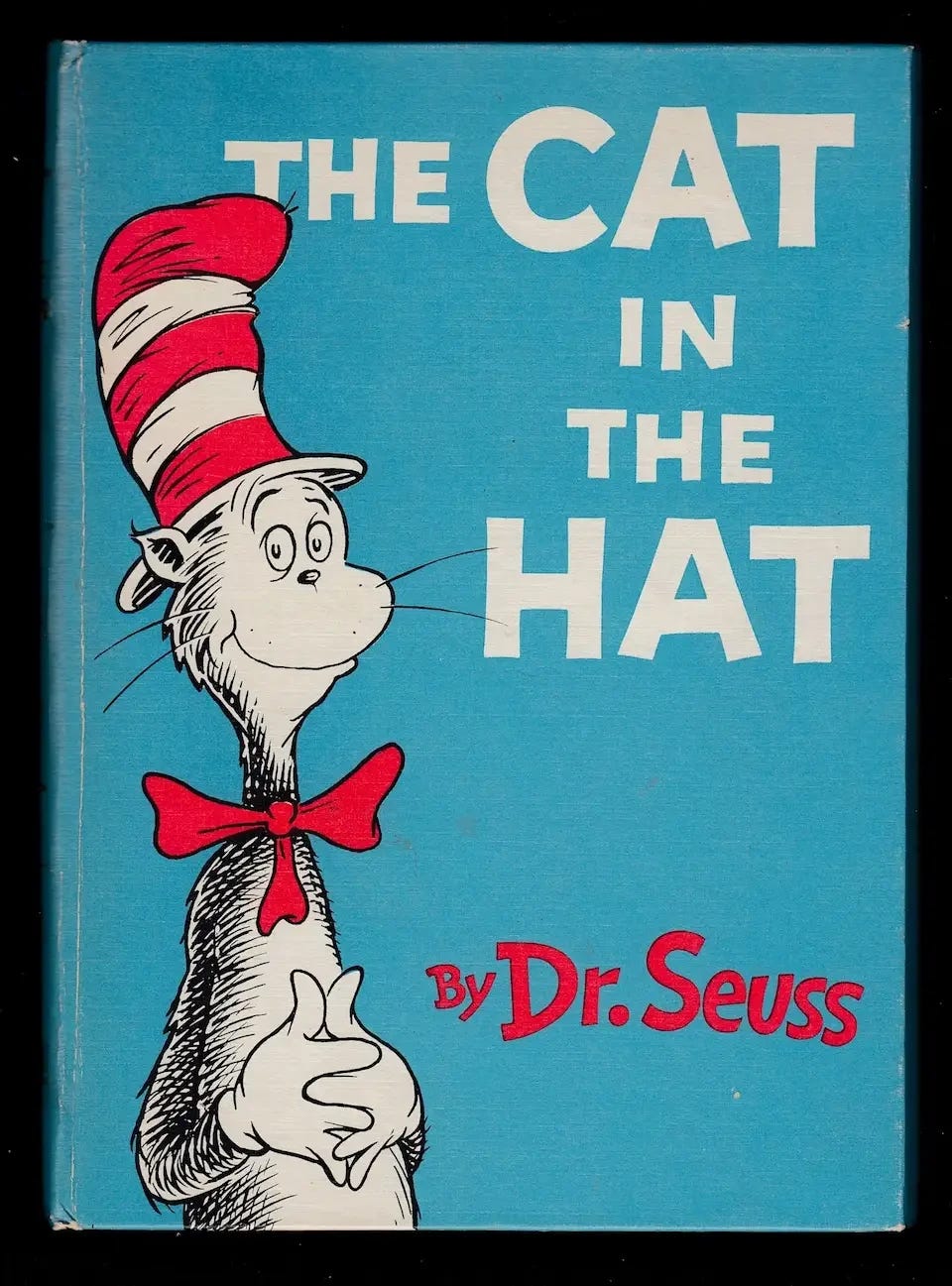

The first edition of Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, published in March 1957, should be a $30,000 book, like Curious George and The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Arguably, The Cat in the Hat, which currently retails for $2,000 to $4,000 (depending on condition) is more important than either of those titles.

My next first edition list, devoted to the Tom Garner collection of Ray Bradbury, should post on October 20.

At the beginning of 1957, Ted Geisel, writing as Dr. Seuss, was a solid mid-list children’s author whose books sold hundreds or thousands of copies per year. Most of his income came from freelance advertising work. By the end of the year, after the publication of The Cat in the Hat and How the Grinch Stole Christmas1, he was one of the bestselling writers in America, in any genre. His financial goal had been to earn $5,000 per year; by 1959 he made that much every ten days.2

The Cat in the Hat led directly to the Beginner Books series and to a host of competing titles that revolutionized children’s book publishing in the 1960s.

The only reason The Cat in the Hat, one of the most significant and enjoyable children’s books ever, is still reasonably affordable is because 19 out of 20 copies of the The Cat in the Hat sold by booksellers as first editions are not first editions.

The problem is that nobody knows how to tell the 19 later printing copies from the one first printing.

TL;DR Summary of the Current State (2025) of The Cat in the Hat Edition Points

Educational Issue (Houghton Mifflin, February–April, 1957). The earliest copies seem to have the pages sewn in one gathering (signature), a rounded spine, and a white circle on the rear board with the book’s title in black. Instead of “Random House” on the title page, it reads, “Houghton | Mifflin | Company | Boston: The Riverside Press.” The front cover does not have the “For Beginning Readers” logo found on the trade issue and the author’s name is set farther from the bottom edge to fill the space. Priority with reference to the trade issue is not certain. Later issues have flat spines, three gatherings, and a “Read By Yourself” logo on the back cover (which occur in various combinations).

Trade Issue (Random House, March 1957): The first printing, reported at 12,000 copies, the second printing in April, and subsequent printings to September 1958, totaling more than 250,000 copies, cannot currently be distinguished. This earliest variant is bound in matte-finish boards and has one gathering (signature). The dust jacket, priced at $2.00 (200/200 at the top of the front flap) and lacking the statement “Printed in U.S.A.”3 at the bottom of the back flap, is required to identify the trade issue. Copies with no price on the jacket but one gathering and matte-paper covers are book club editions (they have been incorrectly described as “transitional copies”).

Canadian Issue (Random House of Canada, March? 1957): Listed on the copyright page of the early variants but not recorded in any bibliography, as far as I can tell. Reviews in Canadian newspapers give the price as $2.50. Probably conforms to the trade issue except for the jacket price.

The standard points of the first edition of The Cat in the Hat that children’s book aficionados know to look for—$2.00 price, single gathering (signature), matte- (or flat-) finish boards—do not denote the first edition.

If a book doesn’t have those points, it’s definitely not a first printing.

If it does have those points, it is still probably not a first printing.

At the upper echelons of the book trade, this is an open secret. Rather than call copies of The Cat in the Hat “first printings,” a lot of dealers refer to the “first issue.” This is a euphemism and incorrect. Editions have printings, printings have issues, issues have states. If the term is to have any meaning, issue cannot both refer to groups of printings (as it is used for The Cat in the Hat) and subsets of printings (most everything else). We have a word to handle bibliographical uncertainty: variant. As in “earliest known variant of The Cat in the Hat.” But issue sounds better for marketing purposes. Hence, Scott’s collecting rule #25:

If a dealer uses the word issue without citing a bibliography, they are probably hiding something.

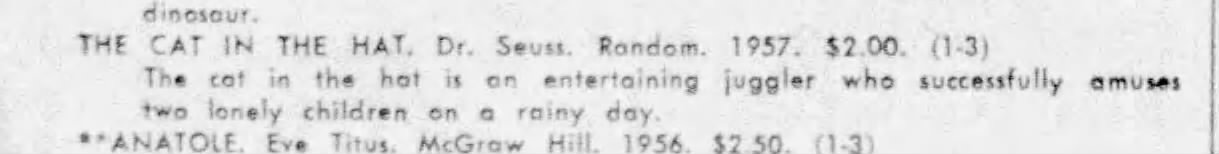

It took a long time for collectors and dealers to accept that $2.00 jackets on The Cat in the Hat denoted the earliest printings. Early copies of The Cat in the Hat are found with two prices on the dust jacket, $1.95 and $2.00. Some people liked to argue that the $1.95 copies came first because prices go up, not down. Finally, dealers with the reputation of Helen and Marc Younger (of the late, lamented Aleph-Bet Books), and the collector Dan Hirsch, settled the matter when they published what is considered the definitive guide to Dr. Seuss in 2002.4

That The Cat in the Hat initially had a $2.00 price was not actually a difficult question. Dr. Seuss’s book was reviewed hundreds of times when it came out with the publication price listed as $2.00. Still, folks with $1.95 copies stubbornly stuck to the prices-go-up logic. When the Youngers published their bibliography, dealers and collectors finally believed it.

The Youngers noted that first editions used matte paper for the covers. About 2006, the collector Stan Zielinski (who I wrote about here), published on his website the observation that the first edition of The Cat in the Hat also has only one gathering (or signature)5. It’s necessary to check the number of gatherings or the paper used on the covers because someone might have married a $2.00 jacket to a book originally priced at $1.95.

And thus we have the two ways to identify first printings of The Cat in the Hat, both essentially the same:

Youngers & Hirsch: “Price 200/200 on front flap of dust wrapper, paper on covers is flat” (p. 28).

Zielinski: “Single signature and at a price of $2.00, with ‘200/200’ on the top right of the dust jacket’s front flap…. All single signature bindings of The Cat In The Hat books have boards with a matte finish.”6

If you read the bibliographies closely, however, you’ll immediately start to see problems with this information.

The Youngers note that “There are many variations in the stitching of first and early copies but no definitive pattern emerges to use this as an issue point.”

Did you catch that—first and early copies? In the text they acknowledge that they can’t identify the first printing. Unfortunately, they listed their criteria under the heading “first printing points,” and most people never read the fine print.

Zielinski does the same thing. He writes, “there were several printings of this ‘single signature/200’ format … These additional printings are identical to the initial first printing, with a single signature binding and ‘200/200’ on the front flap” (emphasis added).

Nevertheless, Zielinski then goes on to describe variations that he calls the “2nd & 3rd Printing[s].” But he’s already conceded that there are multiple printings between the first printing and what he calls the “2nd” printing.

Dr. Seuss himself may well be to blame for the many as-yet indistinguishable printings of The Cat in the Hat. He was very closely involved with the production of his books, choosing paper stocks and matching printing inks to his drawings. In 1960, the New Yorker reported, “Geisel still complains loudly if, in the thirteenth or fourteenth printing of one of his works, he perceives one color to be a tiny bit off register.” No Dr. Seuss book published up to that time has anything like thirteen identifiable printings.

Anyone still grasping firmly to the hope that their copy of The Cat in the Hat is a first printing may reasonably wonder how we know for sure that there were multiple printings of the book with a $2.00 price.

Well, on April 15, 1957, six weeks after The Cat in the Hat was published by Random House, the New York Times ran a story with the sub-heading, “Is in Second Printing.” And in a book about the Beginner Book series, Paul V. Allen writes, “The initial print run of 12,000 sold out immediately, and a second printing followed within a month.”7 By mid-April 1957, Random House was calling The Cat in the Hat, “the biggest event in children’s reading in centuries.” Hyperbole, to be sure, but puffery backed by strong sales. The Cat in the Hat was the second-best-selling book of 1957. You don’t sell that many books from one printing.8

So I started to wonder when Random House changed the price from $2.00, which supposedly indicates a first printing, to $1.95.

The Cat in the Hat was copyrighted on February 28, 1957. Both the Youngers and Zielinski show that the book was still advertised in October 1957 at $2.00. Zielinski’s website says that the $2.00 price was replaced about December 1957, although he told me that he no longer believes this.

Fortunately, newspapers published book prices all the time. The last mention I have found of The Cat in the Hat priced at $2.00 appeared 16 months after it was first issued. A newspaper printed the New York Public Library’s Guide for Children’s Summer Reading, listing The Cat in the Hat for $2.00.

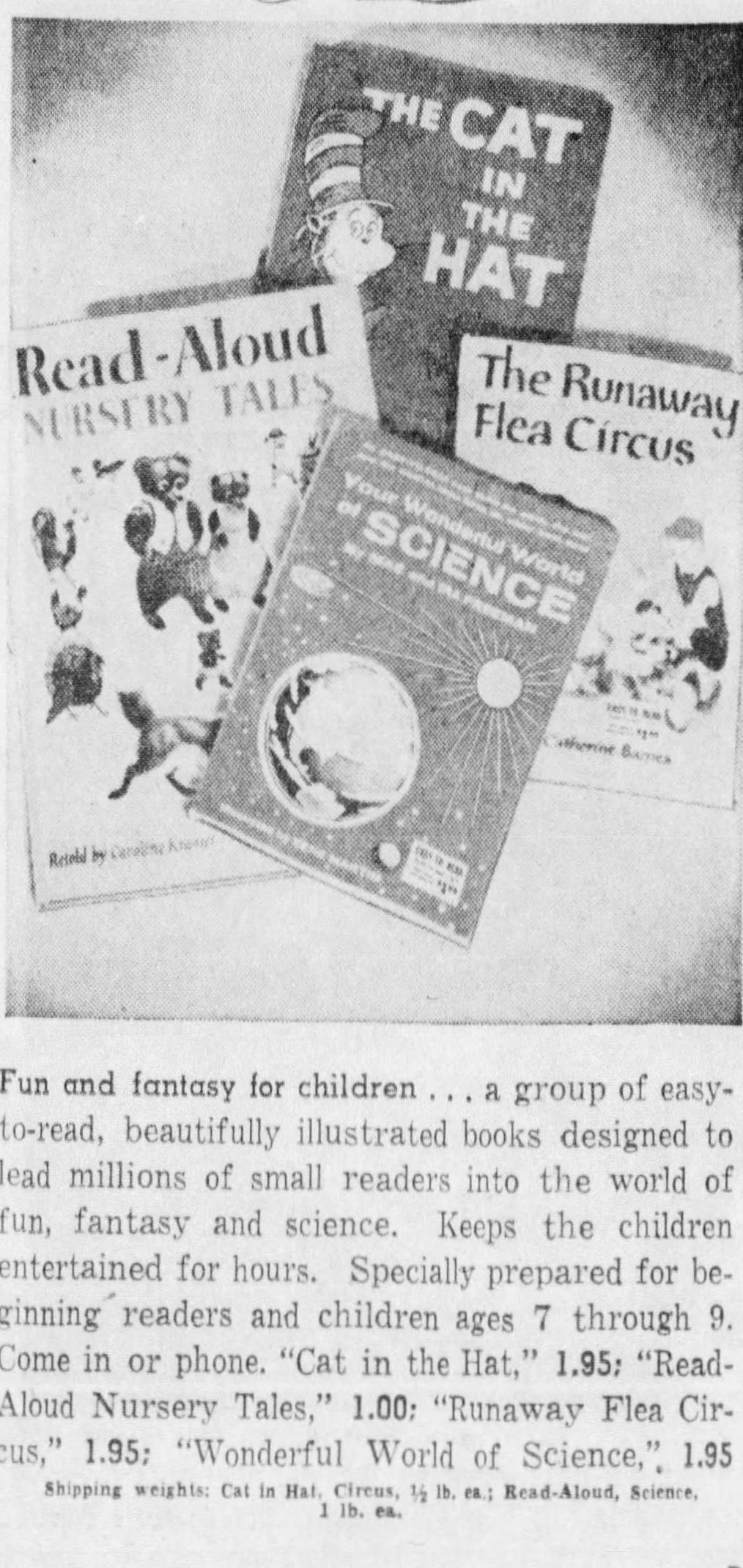

Following the success of The Cat in the Hat, Dr. Seuss formed a new publishing company, Beginner Books, to produce a series of early readers. Random House would be the distributor. Five Beginner Books came out in September 1958. The Cat in the Hat was retroactively made book one in the series. All six titles were uniformly priced at $1.95. Thus we know that copies of The Cat in the Hat, first published in March 1957 at $2.00, hit bookstore shelves with a new $1.95 price around September 1958.

By the end of 1957, The Cat in the Hat had sold 250,000 copies. A year later, the total reached 300,000. If the first printing of The Cat in the Hat was 12,000 copies, then something over 95% of all $2.00 copies are not first printings.9

Most likely, careful examination of the stitching pattern is a key to identifying the correct first printing. Unfortunately, that’s going to be hard to research because we’ll need to look at copies whose provenance can be traced definitively back to March 1957. Copies dating to April or after might be later printings.

I had the bright idea of checking the copyright deposit copy at the Library of Congress. Unfortunately, it’s missing.

If the fact that almost all “first printings” of The Cat in the Hat aren’t first printings is bad news, what about the distinct possibility that the Random House edition isn’t even the first edition at all?

The copyright page of the early copies of The Cat in the Hat reads (in all caps in the original):

Educational edition published by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston

Trade edition published simultaneously in New York by Random House, Inc.

and in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada, Limited10.”

Wait. What’s Houghton Mifflin doing there?

Neither the Youngers or Zielinski even mention the “educational edition.”11

There is some evidence that the educational edition came out before the trade edition. To be fair, the evidence isn’t conclusive, but it is substantial enough that it needs to be addressed.12

The possibility that the Houghton Mifflin edition came first should not be surprising. Houghton’s director of educational books, William Spaulding, asked Seuss to write a book for early readers—a commission that resulted in The Cat in the Hat. The agreement between Seuss, Spaulding, and Bennett Cerf of Random House was that Houghton Mifflin would publish a school textbook edition while Seuss’s regular publisher, Random House, would produce the trade edition for bookstores.

The original plan was for the Houghton Mifflin edition to come out in early 1957, followed by the trade edition. On July 11, 1956, Seuss wrote Random House,

… Houghton-Mifflin… will be releasing my First Grade Reader [The Cat in the Hat] to schools early in Jan. or Feb…. The Random House trade edition won’t come out until later….13

A lot could have changed between July 1956 and the final appearance of The Cat in the Hat, but Seuss expected the educational edition to appear first. The educational edition is listed first on the copyright page (on The Cat in the Hat Comes Back, the Random House edition is listed first). And Kirkus Reviews, a magazine for retailers and libraries, referred to the Random House edition on June 15, 1957 as “a reissue of the earlier Houghton, Mifflin educational edition” (emphasis added).

Working against the idea of the educational edition of The Cat in the Hat coming out before the Random House edition is an article that appeared in the Los Angeles Mirror on April 1, 1957, nearly a month after the trade edition hit bookstores. The author, Bob Campbell, a past president of the American Booksellers Association, wrote that The Cat in the Hat had “just been published” and referred to a future educational edition. “Houghton Mifflin will publish a text edition which they will promote for use in schools” (emphasis added).

One possible explanation of the discrepancy could be that the educational edition was intended to be released in early 1957 and that it was delayed for some reason. More research needs to be done to resolve the question of priority of publication.

(Random House’s archive is at Columbia University in New York. The Houghton Mifflin archive is at Harvard University in Cambridge. Perhaps someone could pull the files and see what the archives have to say. Otherwise, I’ll do it when I’m on the East Coast next spring).

By all accounts, the Houghton Mifflin educational edition was a flop. Schools didn’t adopt The Cat in the Hat as an early reader. In the 1970s, Dr. Seuss told a journalist that “the textbook found no acceptance whatsoever in the school system. Just a few hundred were sold here and there.”14

I found this educational edition brochure picture on the Internet. Unfortunately, it was sent via bulk mail and the meter postage does not include a date.15

Documenting the first printings of modern children’s books is one of the most difficult areas of book collecting. The Cat in the Hat is one of the most difficult of those difficult problems.

We need to toss out the The Cat in the Hat bibliographies and start over, relying on physical evidence of the books as well as contemporary archives to sort out the first printing points.

If first printing points can be determined, most collectors will find themselves stuck with dreaded later printings, but a lucky few will hit the jackpot. If you have a $2.00 copy, I wish you good luck in The Cat in the Hat lottery!

—Scott Brown, Downtown Brown Books

I hate to say this, but the first printing points of Grinch are also probably insufficient. Despite a large first printing of 50,000 copies (see Becoming Dr. Seuss by Brian Jay Jones [Dutton, 2019], p. 268), the book sold well and almost certainly was reprinted before the jacket changed in the fall of 1958. Like The Cat in the Hat, all copies in the original jacket are supposed to be first printings, but likely aren’t.

On $5,000 per year and post-1957 book sales, see “Children’s Friend: The World of Dr. Seuss” by E. J. Kohn in The New Yorker (Dec. 9, 1960): “As recently as 1954, he asked his agent…whether he could count on five thousand dollars annually…” Becoming Dr. Seuss adds, “Geisel eventually asked Random House that any royalties beyond $5,000….be deferred and invested in mutual funds” (p. 299). On making $200,000 per year, see Becoming Dr. Seuss (p. 290): “Ted’s own ‘Big Books’ … earned him $200,000 in 1959.”

The 1985 facsimile jacket includes the statement “Printed in the U.S.A.” It otherwise can be hard to differentiate from the 1957–1958 copies.

The First Editions of Dr. Seuss Books: A Guide to Identification.

People in the publishing business refer to a group of folded pages as a gathering. Book collectors tend to use the term signature. They mean the same thing but signature can also refer to the mark used to identify a gathering of pages. I prefer gathering for the group of pages and signature for the mark, just to prevent confusion. But either way is correct. You do you.

Retrieved on October 3, 2025. Captured on the Way Back Machine.

Quoted from page 22 of I Can Read It All by Myself by Paul V. Allen (University Press of Mississippi, 2021).

From Becoming Dr. Seuss. “…reading event”, p. 265; “second-best-selling”, p. 269.

Sale of 250,000 copies in 1957 can be found in Becoming Dr. Seuss, p. 266. Sale of 300,000 copies a year is found in the Daily Palo Alto Times, December 13, 1958.

Neither Zielinski or the Youngers make any mention of the Canadian edition, published at $2.50, nor does Richard Lindemann (Dr. Seuss Catalog [McFarland, 2015]), who lists many editions of The Cat in the Hat. This is odd because it is specifically mentioned on the copyright page of the book.

Zielinski has a cryptic sentence in his write-up of the first (sic) printing points of The Cat in the Hat, “Please note that the review makes no mention of an educational edition.” He’s drawing attention to the short blurb about Seuss’s book in the children’s book review magazine, The Horn Book (June 1957). What he means is unclear.

To his credit, Lindemann (Dr. Seuss Catalog) lists the educational edition, but he is not especially reliable. For example, he incorrectly gives the price of the first edition of The Cat in the Hat from Random House as $1.95. Even a dozen years after the Youngers’ published their bibliography citing the price as $2.00, the $1.95 information stubbornly lingered. Both Becoming Dr. Seuss and I Can Read It All by Myself make errors with the price, too.

Quoted in Becoming Dr. Seuss, p. 266.

I thought about cropping out the background, but decided that all the odd items in the picture were pretty interesting.

Great work to pull all of this together and provide some clarity.

Excellent all the way through.